Stand for something: The complicated politics of the Pledge of Allegiance

December 18, 2017

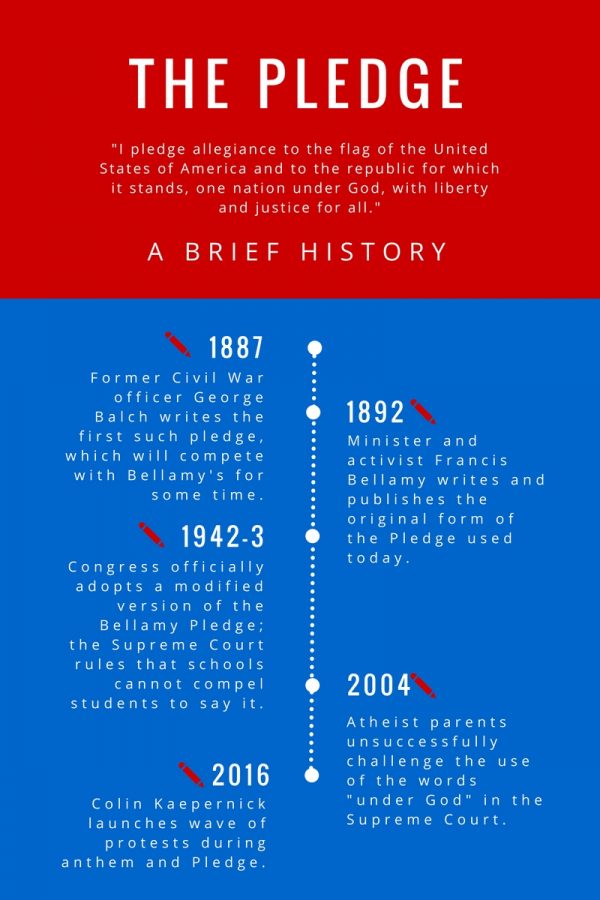

In 1892, the popular children’s magazine The Youth’s Companion published a short patriotic affirmation, inspired by the burgeoning “schoolhouse flag” movement that encouraged the education system to instill a stronger sense of national pride in American youth, as composed by the Baptist minister and prominent socialist Francis Bellamy. This affirmation would soon become known as the Pledge of Allegiance, spreading to schools and other venues throughout the country.

In 1942, Congress gave its approval to the statement; in 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a bill, adding the words “under God,” in a Cold War effort to distinguish the United States from the officially atheist Soviet Union. This form remains in use today.

Throughout its existence, however, the Pledge has attracted controversy from several corners of society. Atheists and other religious minorities have long complained of the oath’s allegedly exclusionary religious language, while several groups on the political left have criticized its verbal commitment to “liberty and justice for all” in the face of what they see as pervasive, institutionalized racial and gender discrimination.

Others simply view the Pledge’s nationalistic attitude as dated, over-the-top, and grossly jingoistic, something jarringly out of place in a modern, global, pluralistic society. Regardless of motive, such opponents frequently voice their concerns through a simple, nonviolent form of protest: sitting or kneeling when asked to stand for the Pledge.

This particular form of protest gained momentum in August of 2016, when then-49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, against the backdrop of the burgeoning Black Lives Matter movement and growing sociopolitical tensions across the country, chose to sit rather than stand for the National Anthem in protest of what he described as institutional racial inequality. Soon, more members of the National Football League (NFL) followed, spurring both support from those sharing Kaepernick’s views and condemnation from those such as President Donald Trump who saw such actions as disrespectful of both the nation and those who gave their lives defending it. These actions on the football field in turn inspired students to take a smaller, though no less significant, action in the classroom.

“The phrase ‘with liberty and justice for all’ is just patently untrue. With the problems with police brutality and just generally, the deck is stacked against people of color and women in this country, and I don’t believe that the phrase ‘with liberty and justice for all’ is true, so I decided to stop [standing for the Pledge],” senior Khalil Jackson said.

Refusing to stand for the Pledge has quickly become both a powerful form of political speech and an instantaneous, divisive political marker.

Refusing to stand for the Pledge has quickly become both a powerful form of political speech and an instantaneous, divisive political marker.

To supporters of the movement, it serves as the stamp of an involved, “woke” citizen devoted to fighting injustice.

To opponents, it marks the protester as a disrespectful, unpatriotic ingrate failing to recognize or respect the privileges of living in the U.S. and the sacrifices made by members of the country’s armed forces.

An issue this fraught with political and frequently religious and racial divides can become easy fodder for the culture wars, and indeed it has. In October, for example, Vice President Mike Pence walked out on an Indianapolis Colts football game when members of the team “took a knee” for the anthem, thus presumably signaling Pence’s patriotic bona fides to his (and the President’s) strongly nationalistic base. Meanwhile, in September, Representative Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) knelt on the House floor to show solidarity with protesters in the NFL and elsewhere.

Students who choose to protest in the classroom, however, can face contempt, derision, condemnation, and in some cases punishment for their actions, especially in areas of the country where the general populace tends to oppose such forms of protest. In October, for example, school officials expelled Houston high schooler India Landry for sitting instead of standing for the Pledge of Allegiance. When her family filed a lawsuit against the school, the case became national news. The Supreme Court decreed in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette that schools could not force students to say the Pledge against their will—although opponents might argue that the ruling does not apply to the physical act of standing, only to the spoken words themselves.

“I feel it’s unconstitutional for the Pledge to be broadcast in schools because of the phrase ‘one nation under God,’” Jackson said. “It’s a violation of the First Amendment for that to be in public schools.”

Regardless of the surrounding freedom-of-speech issues, though, even people who acknowledge the protesters’ right to take these actions or recognize their reasoning may still consider such protests unwarranted. Some, with a particular eye to the sacrifices made by veterans beneath the flag, may see it as deeply disrespectful and unpatriotic to refuse the flag the proper respect as the symbol of one’s country. Others may simply see such divisive posturing as an ineffective way of achieving one’s socio political goals with a populace frequently deeply sensitive to such displays.

“I think, out of a sign of respect, that students should stand for the Pledge,” Honors Government and Magnet Leadership teacher Sam Fraundorf said. “But if they choose not to recite it, then obviously that’s their choice. You shouldn’t force anyone to do anything, especially in a situation where we are separating our values, religious beliefs, and things like that from a school-type setting.”

In recalling his composition of the Pledge, Francis Bellamy wrote, “The simple patriotic idealism of the former generations was being forgotten in the current materialism. That old spirit must be revived. The place for the revival to begin was in the public schools. The new generation must be taught an intense love of country.”

Whether “intense love of country” should serve as a guiding value for today’s generation, and whether the Pledge continues to serve as an appropriate demonstration of that love, may constitute a separate question altogether.