Good Grief: How others cope with loss

April 18, 2018

The loss of a loved one can leave a person with a feeling incomplete. Without time and space to properly grieve, this feeling of may persist for years on end, resulting in major negative impacts on someone’s life.

The journey from “normal functioning” to the “return to meaningful life” does not come free of obstacles. Each person deals with grief and loss but does not walk the same road.

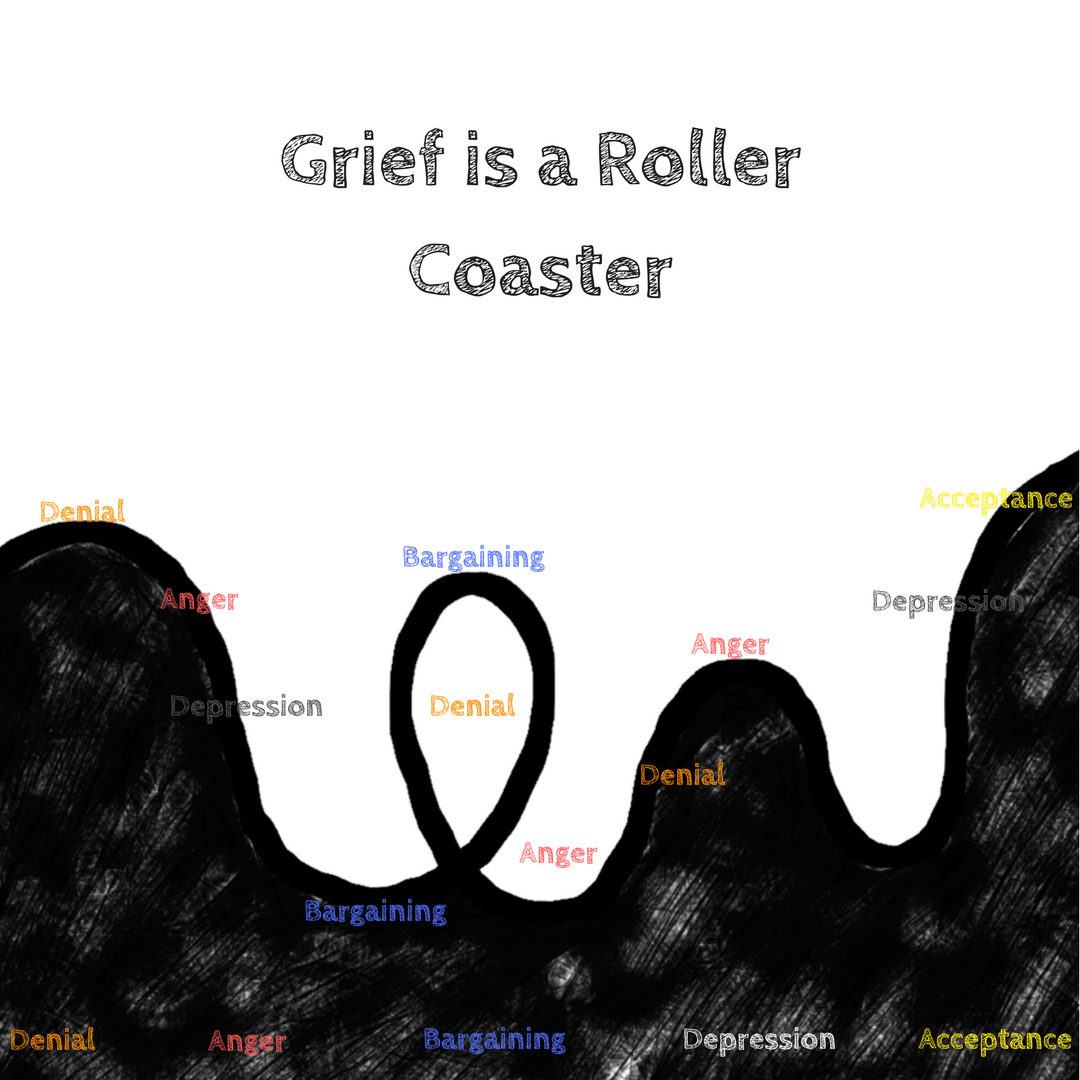

The most popularly recognized theory on the cycle of grief, the Kübler-Ross theory, describes the grieving process as a chronological set of five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Another version of this model, similarly popular and widely known, includes seven stages. These steps, as listed by Recover-from-grief.com, include shock and denial; pain and guilt; anger and bargaining; “Depression” (though not clinically diagnosed by a physician, this site felt reticent to claim the word depression without placing it in quotation marks to designate the difference between clinical and symptomatic), reflection, and loneliness; The Upward Turn; reconstruction and working through; and acceptance and hope.

Jason Rhoads of solo practice Jason Rhoads Counseling Services, LPC in Smyrna, GA claims that grief, despite these models, does not conform to a specific pattern.

Michayla Cherichel

Michayla Cherichel

“You don’t complete a phase, then go to the next. You can go in between, you can go backwards, forwards. You can start in the middle. I think it’s an evolving thing; I don’t think it’s a linear process. It’s a good marker of ‘this is what you could experience, these are the different phases that you could go through,’ and some people may skip one. I think you may even come back down the road. If you skip the ‘anger’ phase maybe two years down the road you find yourself really angry about the situation,” Rhoads said.

Using the popular “TED Talk” platform, Susan Delaney, Bereavement Service Manager at The Irish Hospice Foundation expounds on her belief that the five stages of grief do not exist.

“There’s no five stages of grief. There never was. If someone mattered to you in life, they continue to matter to you after they die. You just have to find a different way to relate to them,” Delaney said.

Delaney argues that “given that grief impacts all of us, it’s extraordinary how many misperceptions that are out there about it.” She says that people talk about overcoming grief in the same way that they talk about the flu.

“Can you remember the last time you had the flu? You can’t think straight. You are just walking flu. You wake up one day and it’s the worst day of the flu, but then the chances are the next day the symptoms are going to lessen and lessen, and the flu symptoms recede. There’s no closure when we’re talking about grief. Grief changes us. It transforms us. So let’s let go of the idea of getting over grief. It doesn’t happen,” Delaney said.

Sophomore Maddie Dean affectionately refers to her late grandfather as Pop Rich. As a third grader, Dean lost Pop Rich to a combination of severe diabetes and old age. On the eve of his passing her grandfather gifted her with a bag of cookies. She planned to call him the next day to express her appreciation for the treat, but learned of his death instead.

Dean realizes her experience with shock and denial upon Pop Rich’s death.

“I didn’t believe it until I went to his funeral,” Dean said.

Dean describes her grieving process as giving herself time to cry and emotionally breakdown, withdrawal from social media and the Internet, physical social isolation, and allowing herself “time to reflect on the happy moments.”

She describes the inevitability of death and loss as something that freaks her out because “you never know when your last day is going to be.” Because of that uncertainty, an unchangeable reality, Dean makes sure to actively participate in life and do her best to cherish each experience with the people she loves.

Three years after learning of her biological father’s passing, Elizabeth Ferguson beams with joy as she proudly holds two pictures. The first (left) shows her father, Jason Ferguson, posing for his senior picture. The second (right) shows Ferguson, her father, and her mother, Sarah Edwards, as they gaze fondly at their newborn daughter.

Similar to Maddie Dean, magnet student sophomore Elizabeth Ferguson experienced and continues to experience denial during her most grief-inducing trial.

Raised by her mother and stepfather, Ferguson, for much of her life, remained oblivious to the truth about the identity of her biological father.

“It was in seventh grade and I had just turned twelve. That’s when I found out about my real dad,” Ferguson said.

She reminisces on the feeling of absolute joy that overwhelmed her when she discovered that she actually did “have a dad out there.”

“When I found out about my real dad I was like, you know, ‘I really want to meet him.’ I never did get the chance because that November, I remember, my mom stopped me after school and was like, you know, ‘I know how you wanted to meet your dad and everything but he died.’ It stuck with me for a while and it still haunts me every year. There is still a part of me that’s like, ‘Maybe it’s a lie. Maybe it’s some horrible, rude trick on us and maybe he really is still alive… .’ That’s what I always think everyday. I feel like I went through all the processes and it comes back to November and I jump back to the start again,” Ferguson said.

The jarring reality that humans cannot control the time when death strikes, nor have any way of finding out creeps into Ferguson’s thoughts in what she calls “shower thoughts.”

“I’ve seen people die, and I know people who have died. It’s part of nature. It can be from old age, it can be from cancer, or it could just be from a freak accident. It’s made me realize, you know, don’t take people that you really love and care about for granted because one minute they may be there and… you want to spend time with them and the next minute they’re gone. It’s made me appreciate my family more and realize, hey, everyone doesn’t last forever,” Ferguson said.

Michayla Cherichel

Michayla Cherichel

Perspective, as Ferguson mentions, plays a key role in the differences in grieving styles of individuals, even within a family.

“Everyone has a different way of grieving. For me it’s the grieving of losing a father, for my aunt it’s the grieving for losing her brother, for my grandmother it’s the grievance for losing a son so early. It just depends on someone’s viewpoint,” Ferguson said.

Ferguson brings up the idea that a person mourning the loss of a child or another close family member will endure a more severe level of pain than someone dealing with the loss of an acquaintance, such as a classmate or a coworker with whom they lacked relationship.

In a video titled “Physical Effects of Grief” Illustrator and author Jackie Schuld, author of picture book Grief Is a Mess, a visual depiction of grief and the various forms it takes on, describes the differences in grieving habits within her family after the loss of her mother.

“When my mom died, which on February 23rd will be two years, each member in my family experienced it differently. For instance, some people gained some weight… I actually felt sick quite a bit so I didn’t eat much and I lost weight,” Schuld said.

Schuld also mentions chronic exhaustion, both insomnia and oversleeping, “feeling like you don’t have the energy to conquer anything,” and feelings of despondence as common emotions and physical states that she and her loved ones experienced while grieving her mother’s death.

“What’s hard is to separate the physical from the emotional and mental. They’re just so intertwined… It all just kind of weaves together,” Schuld said.

Nikira Reece, a South Cobb High School student, also saw differences in grieving habits within her family in the death of her grandfather, whom she called Papa.

“He was like my closest friend at the time. It’s different… The family aspects that I used to have while he was around in one part of my family, it’s dimmed down a little bit. I don’t see a lot of my family anymore. The family that I was close to that he was connected to as well, because he’s not my blood grandpa… his daughters, for example, they kind of went away after he died and so I haven’t seen them in years. People that I was really close to went away as well,” Reece said.

Michayla Cherichel

Michayla Cherichel

What’s Your Grief?, a platform for grievers and grief education, offers several reasons for this phenomenon of family misunderstanding and dysfunction after loss. One of these, the act of avoidance, can involve grievers distancing themselves from their family through the means of intensified focus on work, substance abuse, “denial of feelings and emotions”, physical isolation, etc. This idea, to most people, appears the opposite of logic. However, What’s Your Grief offers a comprehensive explanation.

“When we talk about avoidance in regards to grief, we are usually referring to experiential avoidance. Experiential avoidance is an attempt to block out, reduce or change unpleasant thoughts, emotions or bodily sensations. These are internal experiences that are perceived to be painful or threatening and might include fears of losing control, being embarrassed, or physical harm and thoughts and feelings including shame, guilt, hopelessness, meaninglessness, separation, isolation, etc,” What’s Your Grief said.

Perhaps Reece’s aunts saw physical distance from family as the best way to heal from the pain of losing their father. Perhaps their personal grieving processes, like Maddie Dean, includes a period of isolation.

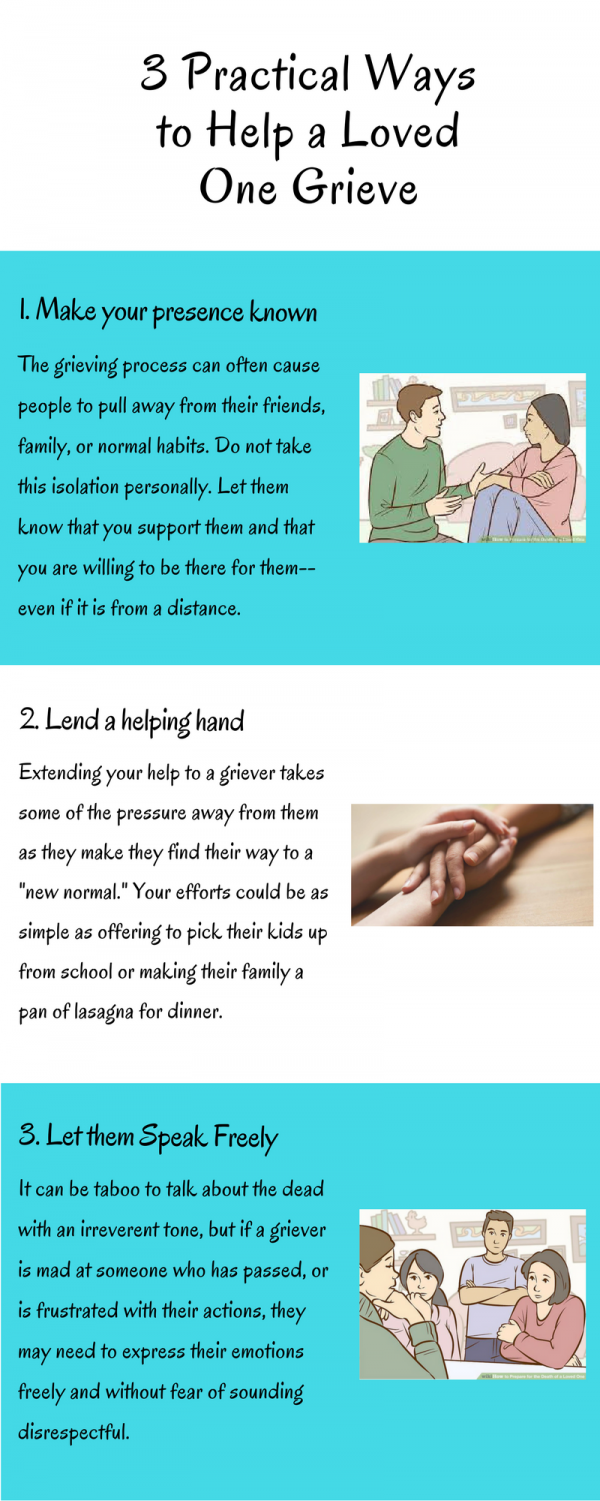

Jason Rhoads, an aforementioned counselor, acknowledges that while isolation may serve as a necessary tool in healing, community remains crucial.

“I don’t think there is any magic thing that you need to say to someone. Being present with them and just letting them know you’re there is key. It’s more about a state of being present and being able to… send a message to them, that you’re able to endure their pain,” Rhoads said.

Michayla Cherichel

Michayla Cherichel

WatchWellCast, a YouTube channel that explores “the physical, mental and emotional paths to wellness,” reiterates the central idea of the grieving process: “Grief is a process, not a task. While you might identify with all of these steps, you’ve got to remember that grief is less like a staircase and more like a rollercoaster. It’s natural to have an uneven journey with your grief.”

The aftermath of loss varies from experience to experience and remains exempt from compartmentalization. It serves as a wake up call to what humans take for granted on a daily basis.

The process of grieving allows people to explore their own fears, discover a new sense of self, and even reinvent themselves or their perspective on life and how they choose to live it.