Latinos: On the journey to a better education

December 16, 2019

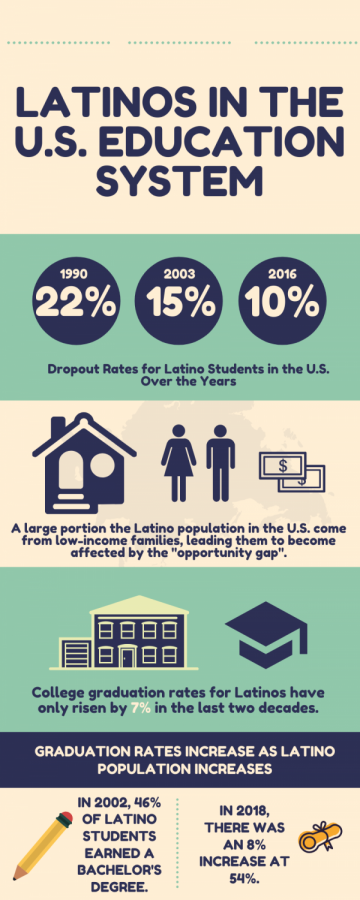

According to the Census Bureau, the dropout rate of Latino students reached an all-time low in 2016 at 10 percent. Five years earlier, the rate hit a whopping 16 percent. In the fall of 2015, Hispanic students made up more than a quarter of students enrolled in the American public school system, predicted to increase to about 29 percent in a decade from now. As the Latino population increases in the United States due to increased immigration, Hispanics progressively enroll in public schools across the country, only to remain as one of the ethnic groups with the highest dropout rates and lowest higher-education enrollment. Education remains a priority to a large portion of Americans, public education giving everyone the opportunity to become successful. If this is the case, then why have Hispanics and Hispanic-Americans fallen so far behind in regard to such a seemingly important American privilege?

Foreign-born Latino students become more likely to fall victim to the educational “opportunity gap”—which refers to how race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and other factors can perpetuate lower educational aspirations and achievement—compared to their second and third generation American counterparts. Despite their generational status, one-third of U.S. Latino children live in poverty and two-thirds live in low-income households, the opportunity gap still managing to strike harshly.

“I’ve seen Latino students, especially around the area where I’m from, drop out of high school because they see their households struggle economically. Often times they prioritize earning money now over finishing school and higher education. They see opportunities where they could make a good living quickly without school and take it,” Honduran senior magnet student Ana Barahona said.

Socioeconomic circumstances can ultimately affect a student’s work ethic and determination; from simply graduating high school to earning a college degree, a large portion of Latino students may find it difficult to find the motivation to break the cycle of poverty through education, given that their circumstances may force such a mindset onto them. Hope for success when living in poverty— along with low expectations for one’s education— becomes hard to find; the lack of resources and opportunities and advancements in learning render these teens from reaching their fullest academic potential.

Students from low-income families become more than twice as likely to drop out of high school than their middle-class counterparts. As a result, these students may become increasingly susceptible to involving themselves in crime-related activities, especially activities such as selling drugs, where making money for themselves and their families can seem easy. Latino students who come from gentrified areas with larger non-white, low- income populations become increasingly likely to face peer-pressure into participating in such endeavors.

“Teens are desperate to break the cycle of poverty in their family and are willing to take any opportunity they can to break it. In their perspectives, they are going with the most practical, lucrative jobs they can have at a young age,” Barahona said.

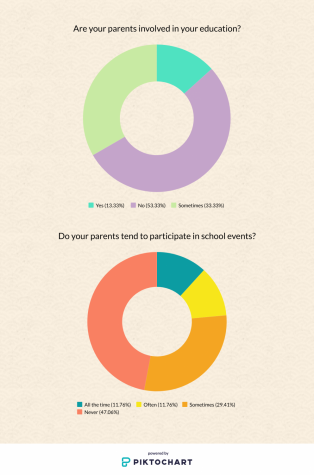

Lack of parent knowledge of higher education also contributes to them lagging behind in their academics. Immigrant families tend to see this constantly; without knowledge of higher education and how the general education system works in America, several first-generation students tend to see a lack of parent involvement and participation in their school endeavors. In the Latino culture, a large portion of old-fashioned parenting deals with the word educación—which places parents’ responsibility on moral education, rather than academic education. Language barriers and social discomfort also become a prominent issue, where Latino parents face limited participation efforts due to only speaking their native tongue, and report less welcoming experiences at their children’s schools in result

“I know a lot of other Hispanic parents who don’t know how to read or speak in English, which leads them to not really participate in their child’s education or at their schools. When I did not know how to speak English too well, I couldn’t really invest myself in my daughter’s education because of the language barrier,” Barahona’s mother said.

College education becomes another factor to take into account with a shifting U.S. population. As Latinos increasingly graduate in the American public high school system, the number of Latinos enrolling in college and completing their college degrees should increase as well, right? According to a report by The Condition of Education in 2017, college graduation rates for Latino students rose only by seven percent in the past two decades. In 2010, 54 percent of Hispanic students graduated with a bachelor’s degree within 4-6 years, compared to white students at 64 percent and Asian students at 74 percent.

A large portion of Latinos who actually want to attempt to attend an institution of higher education face other issues. Nearly two-thirds of Latinos end up in overcrowded and underfunded community colleges and second-tier universities across the country, limiting their options when it comes to a successful education, and only 15 percent of Latinos manage to attend one of the 500 most selective universities in the United States.

Although a large variety of Latino students have faced several educational barriers due to socioeconomic status and low expectations for decades, a new generation seeks to defy stereotypes and become the change that the world currently sees in U.S. education. More and more Latinos currently head into institutions of higher education; in 2002, 46 percent of Hispanics earned a Bachelor’s degree, while in 2018, the number rose to 54 percent.

“I feel like more and more Latinos are finding the aspiration to attend and actually finish college with a degree. In my family, the younger generation is aspiring to go to college more than the older generation, and I feel like it’s because ‘college culture’ is becoming bigger overall in America, where the emphasis on having degrees to be qualified for future jobs is increasing,” senior Jacqueline Ortiz said.

According to the U.S Department of Education, the college-bound rate for Latino students shifted from 22 percent to 37 percent between 2002 and 2015. This helps shape the idea that Latinos have found a progression in their education success rate in recent years. The expectations that Latino youth will continue to thrive in their educational pathways in the United States will not fall according to the statistics taken over the past two decades, where more high schools and universities see Latino students graduate every year, taking the steps necessary towards higher education.

Self-motivation and parent involvement, in the end, can impact a student’s academic future in the long run. If school systems search for better ways to reach out to those students left behind because of their socioeconomic circumstances, Latino academic excellence and aspirations to continue into higher-education would surely skyrocket. Forming connections between a child’s school and the child’s parents could also encourage parents to push their children to become better students, starting with more availability to educational information in their native languages.