Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

The dream of Atlanta: Historic Leo Frank case provides lesson for Marietta today

April 26, 2017

Warning: This story contains sensitive information and pictures that may be inappropriate for some readers.

Lyrics from Alfred Uhry’s Parade, the Broadway musical about the Leo Frank case, proclaim “the dream of Atlanta.”

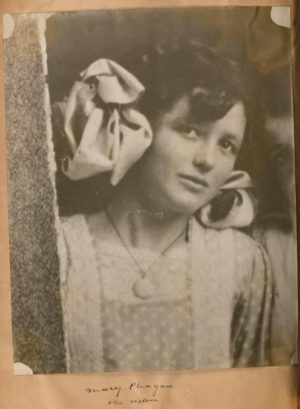

A cool spring breeze wafts over the town of Marietta as the air buzzes with excitement. The day, April 26, 1913, marks Confederate Memorial Day and the thirteen year old Mary Phagan heads to the National Pencil Company in Atlanta to pick up her weekly pay of $1.20 ($29.55 in today’s dollar for her twelve hours of work). The Confederate Memorial Parade will occur tonight, gathering the town together, but Phagan will miss the very event that brought her to town. The police will find her body, battered and lifeless, in the basement of the factory later that night.

Phagan’s death stirred a controversy that spurred on two years of judicial proceedings, culminating in the 1915 lynching of Jewish factory superintendent Leo Frank by Marietta citizens and increasing levels of anti-Semitism and xenophobia that characterized the South until the end of the Civil Rights movement.

As Marietta approaches the 104th anniversary of Phagan’s death, the story of Frank and Phagan lives on in museums and history books, but fall out of the minds of local citizens. The City of Marietta placed a historical marker at the site of the lynching, 1200 Roswell Road, in 2008, but removed it in 2014 due to construction, and Waffle House built a location on the site in 2016. However, the haunting memories of the case still lie beneath the new construction, serving as an omnipresent reminder of the power of regional division and warning a new generation of the dangers of mob mentality.

Phagan’s grave, located in the Marietta Confederate Cemetery, stands tall with kids toys at the base brought by local citizens.

An April evening

Phagan, born on June 1, 1899 to tenant farmer parents who moved to Marietta from Alabama to capitalize on the financial success of the city, set out to pick up her weekly pay from the National Pencil Company downtown on the afternoon of

The young Mary Phagan poses for a photograph.

Confederate Memorial Day, with plans to attend the parade later in the day. Frank, the last person to see her alive, paid her wages. The time in between him paying her and the factory’s watchman Newt Lee finding her body in the basement, abused both physically and possibly sexually, offers the deepest mystery and the news of her death sparked outrage in the public.

The next morning, the police contacted Frank and began to find evidence against him. He claimed that he stayed in his office for at least twenty minutes after Phagan left, but another factory worker, Monteen Stover, claimed she did not see him when she picked up her pay shortly after. Furthermore, Lee, who the police initially suspected, revealed that Frank called after leaving the factory to verify that “everything was all right,” an out-of-the-ordinary move. They also found a pinkish-red stain in the corner of the girls’ dressing room that the State claimed as blood but Frank claimed to be red varnish.

A photograph taken of Jim Conley.

Using this as evidence, the police arrested Frank. They brought him to trial and put the National Pencil Company’s African-American janitor Jim Conley, who admitted to helping Frank move Phagan’s body, on the stand as the main witness against him; the police had arrested Conley earlier after finding him washing red stains out of his shirt.

Further evidence included a statement by Frank, drawn from questioning, in which the prosecution, led by Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey, removed all of the questions and compiled his answers into one paragraph without context, a piece of cord and rag found around Phagan’s neck, wood chips with red splotches on them from the floor, a bloodied shirt found at Newt Lee’s home, and a pad of paper belonging to Conley. Police found two notes resting by Phagan’s body, purportedly written by Mary Phagan and blaming the murder on Lee; Conley later admitted to writing the letters at the request of Frank.

Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey poses for a photograph.

The compiled evidence and testimonies in brief form 318 pages of documents, including more than one hundred witnesses for Frank’s character. As the trial progressed, contradicting statements and evidence from Conley, who provided more than four conflicting testimonies, and other witnesses, as well as interference by the media, led to myriad opinions from either side. The jury eventually convicted Frank and sentenced him to death.

In an attempt to appeal, Frank contacted constitutional lawyer and member of the American Jewish Committee Louis Marshall, who gave Frank’s lawyers, led by Luther Rosser, Reuben Arnold, and Herbert Haas, advice on how to appeal that they ignored. They filed three appeals to the Supreme Court of Georgia and two to the U.S. Supreme Court claiming procedural problems and public influence on the trial. The courts denied each appeal.

Georgia governor John M. Slaton next reviewed the case, reading over 10,000 pages in documents and visiting the pencil factory; he eventually decided on the injustice of Frank’s trial and commuted Frank’s sentence from the death penalty to life imprisonment under the assumption that evidence would lead to Frank’s eventual freedom.

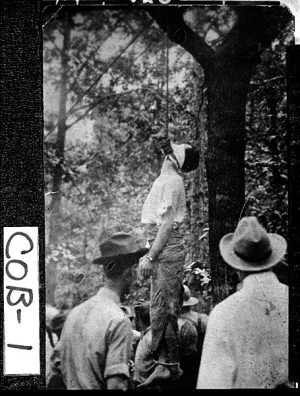

By the time of the commutation, more than two years had passed since the initial murder. A prison farm in Milledgeville, Georgia held Frank, and on August 16, 1915, a number of citizens of Marietta broke into the prison, dragged Frank from his cell back to Marietta, and hanged him the next morning.

A postcard of Leo Frank’s lynching taken on August 17, 1915.

The case sat untouched for 67 years until the eighty-three-year-old Alonzo Mann testified in 1982, that he saw Jim Conley carrying Phagan’s body to the basement of the company on April 26, and that Conley threatened him to keep quiet. The testimony in part inspired the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles to pardon Frank in 1986, though not due to his perceived innocence but because of the issues with his trial and his inability to appeal because of the lynching.

“Without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence, and in recognition of the State’s failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the State’s failure to bring his killers to justice, and as an effort to heal old wounds, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, in compliance with its Constitutional and statutory authority, hereby grants to Leo M. Frank a Pardon,” the board said.

A changing era

The Frank case represents a changing era of American history, especially in the South which still held onto the cleavages of the Civil War. It details a clash between the North and the South, a growing anti-Semitism, and the possibilities of mob mentality.

The years after the Civil War, Atlanta became the unofficial capital of the “New South,” with trade, business, and manufacturing. As the city transitioned from agrarian to industrial, it attracted low-wage workers moving to the city from their previous tenement farmlands, including Phagan’s parents. Atlanta, though sitting in the South’s bible belt, boasted a rich and vibrant street scene. Tobacco, gambling, and cabarets thrived, providing a large market for alcohol before prohibition began in 1920.

Due to the racial segregation intertwined with Southern culture, little anti-Semitism existed in the city, so it presented a great opportunity for Jewish families. Jews gained significant traction in the city, opening large businesses and becoming involved in education, politics, media, and law. The harmony came from an era where business owners, no matter the religion, needed to work together to profit.

In his clemency decision in 1915, Governor Slaton touched on the accusations of racial prejudice against Jewish families, claiming them baseless.

“A conspicuous [(read: prominent)] Jewish family in Georgia is descended from one of the original colonial families of the State. Jews have been presidents of our Boards of Education, principals of our schools, Mayors of our cities, and conspicuous in all our commercial enterprises,” Slaton said.

Frank’s wife, Lucille Selig, came from a prominent Jewish family in Atlanta. Her cousin Simon Selig founded the Selig Chemical Company, another relative, Levi Cohen, helped create Atlanta’s first synagogue, and the family garnered the reputation for their extreme dedication to Jewish culture.

Other than marrying into the Seligs, Frank factored into Atlanta’s Jewish scene starting in October 1907, after his uncle Moses Frank sought to invest in pencil manufacturing and invited Leo, an engineering student, to participate. Frank spent nine months studying pencil manufacturing in Germany and returned to America at Ellis Island on August 1, 1908, stopped in to visit his family in Brooklyn, and then moved permanently to Atlanta. Frank quickly moved up the corporate ladder in the Pencil Company, becoming superintendent, accountant, part owner, and treasurer.

Frank’s quick overtaking of the business reflected that of many other Jews in the area, and sparked outrage with southerners who felt Northern “carpetbaggers,” businessmen who came to the South for cheap entrepreneurship opportunities, threatened their economic sanctity and security.

While the South’s anti-Semitism did grow, the Frank case did not result wholly from a hate for Jews, but from a hate for Northerners as a whole. The South’s ire against the North hit such a high level that, for the first time in the country’s legal history, the court believed the testimony of a black man, Jim Conley, over that of a white man, Leo Frank.

The murder also fell on a holiday deepening the divide between the North and the South: Confederate Memorial Day. The holiday memorialized the men who fought for the South in the Civil War and included a large parade and other festivities. Overflowing sentiment from the Civil War permeated the South and added to the continued divide between north and south.

Marietta citizens celebrate Confederate Memorial Day downtown in 1915.

“This is post-Progressive era politics, and the South, particularly during the 1890s to the early 1900s, goes through a period of vehement, intransigent ‘not sorry for the Civil War-ness,’” AP Comparative Government teacher Carolyn Galloway said. “At that point, we are like forty to fifty years separate from the Civil War, so we have people who are remembering the past who were not part of the trauma of the Civil War. These people, who didn’t actually fight in the war, are building the social stigma into law and culture in the South.”

Tom Watson, the Georgian leader of the Populist Party, only fueled the fire further. Through his publishing company, Watson published his newspaper The Weekly Jeffersonian which, after the turn of the century, set out to attack African-Americans, Catholics, and Jews. Watson published editorials on the Frank case, inflaming public opinion through charged diction and spreading unsubstantiated information. Dorsey, with the goal to run for governor of Georgia, purportedly teamed up with Watson for the political support and reputation.

Watson initially blamed the case initially on the sexual impurity of Atlanta, attacking the Red Light District and the people themselves.

“The horrible fate of Mary Phagan appalls everybody. Here was a pure little girl, hideously outraged, in the centre of a great city, in earshot of the churches, in the midst of a Christian population… all surface eruptions are the evidences of impure blood: get the blood purified, and the sores disappear,” Watson’s Jeffersonian published on May 8, 1913.

Other media of the time heightened social cleavages as well, spreading sensationalized news and interviews to draw in readers. Three newspapers ran the media industry in Atlanta at the time: the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Georgian, and Atlanta Constitution. Nineteen-year-old Atlanta Constitution reporter Britt Craig grabbed the scoop first after overhearing Lee call the police in the Atlanta police station. Craig himself used the case as a reputation-improving job and set out to vilify Frank in the papers. After the lynching, the lynch mob and the media promoted the event by selling postcards of a picture taken at the lynching, and selling pieces of the tree and rope as souvenirs.

In the years following the turn of the century, news outlets operated with significantly less journalistic integrity than today. Sources derived from local gossip, promoted partisan rhetoric, and yellow journalism used to sell papers led to sensationalism on almost every news stand.

“Most major cities had two big papers at the time,” Galloway said. “One came out in the morning and one came out in the afternoon, and one was often more conservative while one was pretty liberal. Depending on the paper you got, you got almost radically different stories, but both of those still tended to be pro-White and sensationalize events dealing with other populations.”

Underage labor also characterized the era, with widespread poverty meaning that

The National Pencil Company, located at 37 to 41 Forsyth Street in Atlanta, GA.

children worked at ages as young as eight to support their families. The National Pencil Company’s work day began at 6:30 a.m. and ended exactly 12 hours later, with one thirty minute lunch break and another thirty minutes over the course of the day for bathroom breaks. The company employed over 170 workers in 1913, the year of Phagan’s death; preteens and teenagers made up the majority of the laborers, with an average age range of eleven to sixteen. Atlanta tended to look the other way at the young workers as long as they brought in money to a struggling class.

Factories offered higher wages than working on rural farms, even though the conditions in the mills barely met health standards. In the city, poor families found more opportunities and a better quality of life, as well as stability; weather may ruin one batch of crops, but factories always need workers.

“You’re coming out of the Civil War and what you have going on is an undercurrent of racial strife in the very segregated society with the severe poverty lines,” Dale Hughes, legal consultant and organizer of the Leo Frank exhibit at Kennesaw’s Southern Museum, said. “You had three different groups: wealthy whites, poor whites, and poor blacks. On top of that you have two very contrasting political parties, one that is very agrarian and one that is more business conservative. Little Mary Phagan, beyond being a victim of a horrific crime, was also a victim of the economic times, and basically a child laborer in extreme conditions.”

Her death also spurred on numerous civil society organizations, including the rebirth of the Klu Klux Klan (KKK) — started by the lynch mob, who dubbed themselves the Knights of Mary Phagan — and the creation of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL).

The KKK, revitalized in 1917 in a cross burning ceremony at the top of Stone Mountain, grew with Tom Watson’s help, staying large in the town of Marietta through the Civil Rights Movement.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, the ADL, created by the B’nai B’rith Jewish service organization of which Frank had served as Atlanta chapter president, strives to protect Jews from prejudice.

“The immediate object of the League is to stop, by appeals to reason and conscience and, if necessary, by appeals to law, the defamation of the Jewish people. Its ultimate purpose is to secure justice and fair treatment to all citizens alike and to put an end forever to unjust and unfair discrimination against and ridicule of any sect or body of citizens,” the ADL’s initial 1913 charter said.

101 years later

Though the case occurred over 100 years ago, its legacy continues to permeate the city of Marietta and its surroundings.

In the early 2000s, an undisclosed source and Steve Oney’s book, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank, created a list of the men involved in the lynching group, which includes prominent families of Marietta that still reside in the town today. The list, though shocking for the families involved, brought together a new avenue for speech about the issue.

“There are significant prominent families that are still here in Cobb County today that were involved in the lynching and up until the late 1990s, people didn’t know who the lynch mob was and people didn’t talk about it,” Hughes said. “As a result of the book, everybody, including those whose ancestors were on either side, all came together and it’s been this wonderful dialogue about what the whole trial means.”

The spot of the murder, 37-41 Forsyth Street in Atlanta, now houses the Sam Nunn Federal Center.

In addition to B’nai B’rith’s Anti-Defamation League, the case serves as an important event in American Jewish history. At the site of the lynching, 1200 Roswell Drive — not even a mile down the road from the Big Chicken —, Rabbi Steve Lebow of Temple Kol Emeth helped to erect two plaques, one in 1995 and one in 2005. The city tore down building the plaques hung on, and removed the historical marker on the spot for construction in 2014. According to the Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT), the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, the Georgia Historical Society, and the GDOT will work to find a renewed location for the marker. Since 2014, the department has made no mention of a replacement location.

On the 100th anniversary of the lynching in 1915, Congregation Etz Chaim, Congregation Ner Tamid, and Temple Kol Emeth held commemoration services for Frank. Congregation Etz Chaim planted a commemorative tree as well.

“Our hope and fervent prayer is that Leo Frank did not die in vain. His memory will live on when future generations view his grave-marker, and they appreciate the shade and magnificence of the natural beauty of the oak tree planted today,” Rabbi Shalom Lewis said.

The case itself also inspired pop culture from 1915 to now. Marietta native Fiddlin’ John Carson wrote the song “Little Mary Phagan” which he performed at the state capitol in protest of Frank’s commutation. It also inspired the 1937 film They Won’t Forget based on a fictionalized account of the case, a 1988 television mini-series called The Murder of Mary Phagan, a 1977 novel, Members of the Tribe by Richard Kluger, with a reconstruction of the case set in Savannah, David Mamet’s 1997 novel Old Religion, a fictionalized first-person point of view from Frank, and Alfred Uhry’s 1999 Broadway musical Parade.

“When I was growing up in Atlanta in the 1940s and 1950s, Leo Frank was mentioned only in hushed tones,” Uhry said. “I remember people getting up and walking out of the room if anyone talked about the case. Why? I think it was some sort of toxic combo of shock, horror and embarrassment. When one of my family’s own (albeit a New Yorker) married into one of the ‘good’ families, and became the focus of rabid anti-Semitism, it was a brutal slap in the face.”

The Chant used Google’s NGram viewer to compile all of the usages of the terms “Leo Frank” and “Mary Phagan” in books since before 1860. The y-axis shows the percentage of Google’s book records containing the search terms. Though not accounting for an overwhelming amount of their records, the two names have seen multiple spikes in popularity as authors publish more books and research.

Atlanta’s William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum opened a special exhibition called Seeking Justice: The Leo Frank Case Revisited that Kennesaw’s Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History displayed in 2015. Hughes and the museum’s Executive Director Richard Banz immediately jumped on the chance to connect the local history to the exhibit.

“I have a concept where I don’t believe in museums,” Hughes said. “Museums present history in a stagnant way. I believe in do-seums. You go through the museum, learn what you can from it, and you say ‘what am I going to do with this?’”

The exhibit showcased an exact replica of Frank’s desk, Mary Phagan’s childhood dress, photos breaking down Atlanta according to class divisions, the door of the Milledgeville prison, and more.

“You go through this exhibit and go ‘wow this sounds a lot like today.’ Then they have this photo of his lynching and as you stand, they actually have a silhouette cutout so that you’re a part of the crowd and it makes you think if you would have said anything,” Hughes said.

A lesson to be learned

Though 104 years earlier, Mary Phagan’s death and the Leo Frank case provide important lessons for today’s society. In a world still plagued with prejudice, division, and increased velocity of information, any number of issues could lead to a similar miscarriage of justice.

“In my mind we have an exactly similar situation today, with political, economic, and religious divisions,” Hughes said. “We have a volatile setting and we have a media that is trying to compete for attention, and this is not anything that we couldn’t also find around the 1800s, 1700s, or 1600s, and so on. The forms of communication were different but these things repeat themselves, so when are we going to learn that and when are we going to do something about it?”