An April evening

April 25, 2017

Phagan, born on June 1, 1899 to tenant farmer parents who moved to Marietta from Alabama to capitalize on the financial success of the city, set out to pick up her weekly pay from the National Pencil Company downtown on the afternoon of

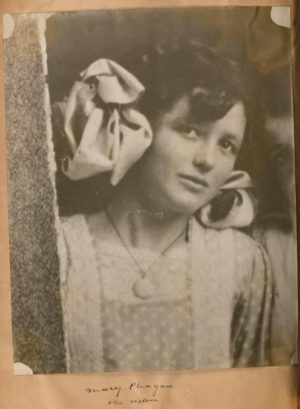

The young Mary Phagan poses for a photograph.

Confederate Memorial Day, with plans to attend the parade later in the day. Frank, the last person to see her alive, paid her wages. The time in between him paying her and the factory’s watchman Newt Lee finding her body in the basement, abused both physically and possibly sexually, offers the deepest mystery and the news of her death sparked outrage in the public.

The next morning, the police contacted Frank and began to find evidence against him. He claimed that he stayed in his office for at least twenty minutes after Phagan left, but another factory worker, Monteen Stover, claimed she did not see him when she picked up her pay shortly after. Furthermore, Lee, who the police initially suspected, revealed that Frank called after leaving the factory to verify that “everything was all right,” an out-of-the-ordinary move. They also found a pinkish-red stain in the corner of the girls’ dressing room that the State claimed as blood but Frank claimed to be red varnish.

A photograph taken of Jim Conley.

Using this as evidence, the police arrested Frank. They brought him to trial and put the National Pencil Company’s African-American janitor Jim Conley, who admitted to helping Frank move Phagan’s body, on the stand as the main witness against him; the police had arrested Conley earlier after finding him washing red stains out of his shirt.

Further evidence included a statement by Frank, drawn from questioning, in which the prosecution, led by Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey, removed all of the questions and compiled his answers into one paragraph without context, a piece of cord and rag found around Phagan’s neck, wood chips with red splotches on them from the floor, a bloodied shirt found at Newt Lee’s home, and a pad of paper belonging to Conley. Police found two notes resting by Phagan’s body, purportedly written by Mary Phagan and blaming the murder on Lee; Conley later admitted to writing the letters at the request of Frank.

Solicitor General Hugh Dorsey poses for a photograph.

The compiled evidence and testimonies in brief form 318 pages of documents, including more than one hundred witnesses for Frank’s character. As the trial progressed, contradicting statements and evidence from Conley, who provided more than four conflicting testimonies, and other witnesses, as well as interference by the media, led to myriad opinions from either side. The jury eventually convicted Frank and sentenced him to death.

In an attempt to appeal, Frank contacted constitutional lawyer and member of the American Jewish Committee Louis Marshall, who gave Frank’s lawyers, led by Luther Rosser, Reuben Arnold, and Herbert Haas, advice on how to appeal that they ignored. They filed three appeals to the Supreme Court of Georgia and two to the U.S. Supreme Court claiming procedural problems and public influence on the trial. The courts denied each appeal.

Georgia governor John M. Slaton next reviewed the case, reading over 10,000 pages in documents and visiting the pencil factory; he eventually decided on the injustice of Frank’s trial and commuted Frank’s sentence from the death penalty to life imprisonment under the assumption that evidence would lead to Frank’s eventual freedom.

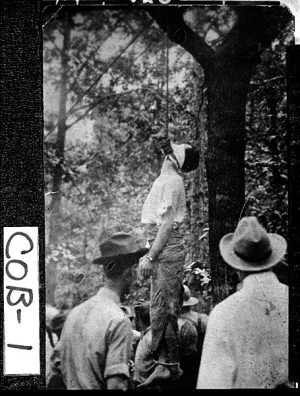

By the time of the commutation, more than two years had passed since the initial murder. A prison farm in Milledgeville, Georgia held Frank, and on August 16, 1915, a number of citizens of Marietta broke into the prison, dragged Frank from his cell back to Marietta, and hanged him the next morning.

A postcard of Leo Frank’s lynching taken on August 17, 1915.

The case sat untouched for 67 years until the eighty-three-year-old Alonzo Mann testified in 1982, that he saw Jim Conley carrying Phagan’s body to the basement of the company on April 26, and that Conley threatened him to keep quiet. The testimony in part inspired the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles to pardon Frank in 1986, though not due to his perceived innocence but because of the issues with his trial and his inability to appeal because of the lynching.

“Without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence, and in recognition of the State’s failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the State’s failure to bring his killers to justice, and as an effort to heal old wounds, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, in compliance with its Constitutional and statutory authority, hereby grants to Leo M. Frank a Pardon,” the board said.