Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Is sleep really for suckers?

May 17, 2017

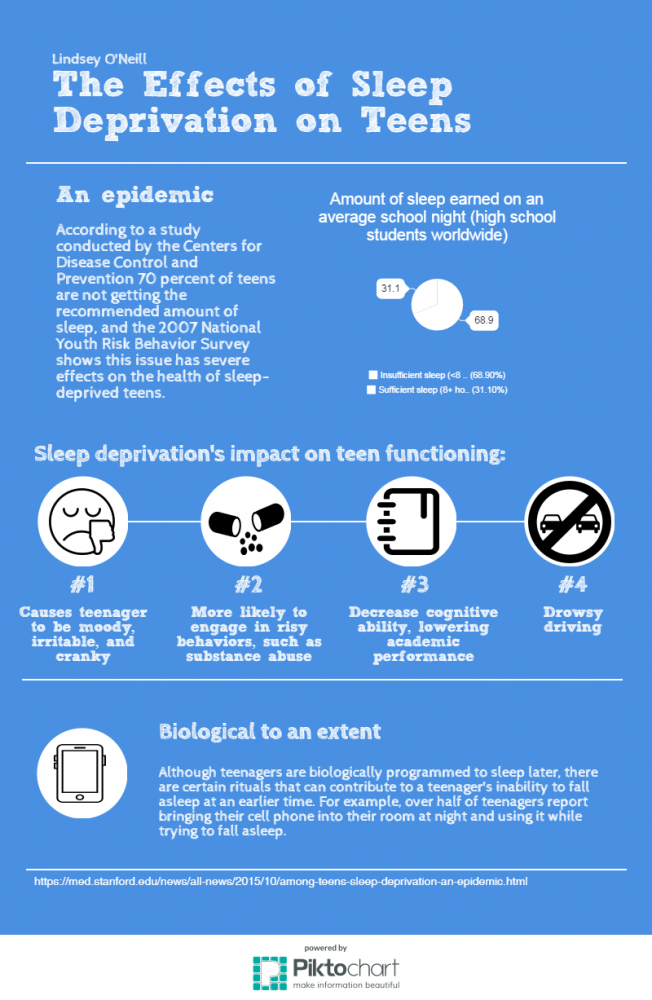

Each night high school students worldwide face the tough decision: to sleep or to study? Whether because of an overwhelming workload or the release of a new Netflix series, teenagers pride themselves on burning the midnight oil, sacrificing sleep.

Unfortunately, the human body cannot handle wakefulness 24/7. During one’s teenage years, their brain undergoes rapid development. According to neuroscientific research, during teenage years the volume of white matter within the teenage brain increases causing dramatic changes in teens’ executive functions specifically cognitive processes responsible for controlling thoughts and behaviors. By depriving themselves of sleep, teenagers put their own growth at serious risk. Yet teenagers continue their habitual late nights and early mornings; then they attempt recovery on the weekends by sleeping into the late afternoon.

NC students roam hallways, carrying not only the weight of binders and books but also the heavy bags hanging below their eyes. As high schoolers, students persistently involve themselves in extracurricular activities as well as multiple AP courses, putting them a step above their peers when college application time rolls around.

Teenagers suffer from a plethora of symptoms on top of constant chronic fatigue. A sleep-deprived individual might experience many changes in mood, suicidal thoughts, and difficulty concentrating, symptoms often dismissed as normal for a teenager in their years of “adolescent angst.”

Regarding long-term effects, sleep deprivation increases an individual’s risk of developing obesity, high-blood pressure, Type 2 diabetes, memory issues, and even accidental death. Although one might feel renewed after “sleeping off” their week on the weekend, the body never totally recovers when deprived from sleep repeatedly. Of course an occasional late night cram session here and there should not greatly impact an individual’s health, but for NC students, late nights add up fairly quickly amounting in serious “sleep debt.”

Sleep does much more for the body’s overall wellness than just improving mood and appearance. While asleep, the regions of the brain responsible for decision-making and paying attention deactivate themselves in hopes of preventing performance depletion the following day. This explains why students struggle with concentrating and retrieving information after not receiving sufficient shut-eye. When these regions of the brain go without rest, naturally their functioning diminishes which explains why teens make rash decisions when they go without catching any z’s.

The teen brain needs nine to ten hours of sleep a night to function properly. A teen who does not receive adequate sleep on a regular basis will likely experience a downward spiral consisting of weakening resilience and poor choices. A growing mass of research suggests a good night’s sleep proves a more successful alternative to an all-nighter. During sleep, the memory making machine parts of the brain communicate with one and other, recapping that day’s “sensory impressions,” forming memories. An all-nighter prevents the body from creating memories from that day; countless hours of studying go to waste if the brain did not properly interpret and store the newly learned information.

“I prioritize studying over sleep because in Magnet you cannot sleep or you will miss a week’s worth of material,” junior Baileigh Krause said.

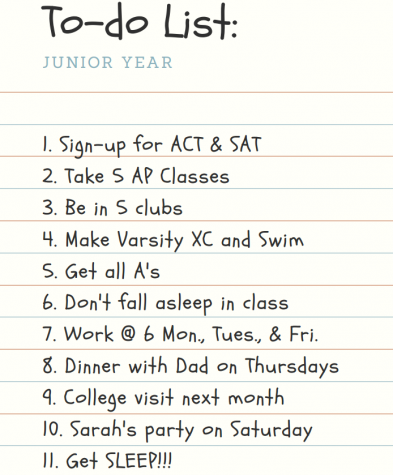

At NC, the Magnet junior year carries a reputation for consisting of a serious workload and very few hours of sleep. Junior year’s difficulty partly exists because of the class load that Magnet juniors often find themselves placed in, but many other responsibilities weigh into the stress.

“I think the hardest part about junior year is definitely not the amount of rigorous classes you are taking, because you have already grown pretty accustomed to those,” senior Celina Cotton said. “It is the fact that junior year is the year where you really have to realize you are becoming an adult.”

As juniors begin mapping out their futures, sleep rarely holds a spot at the top of students’ priorities lists. Although the future seems exciting, the subject rarely comes up without inciting stress; stress leaves students restless and anxiously awaiting the next major test or obstacle they will encounter. Amidst keeping up with their commitments, juniors find themselves arriving at school early for club meetings, test corrections, or early morning practices on a regular basis.

“[You begin to] think about colleges to visit that you want to apply to, sign up for the SAT/ACT (maybe even multiple times), you are becoming captain or holding leadership positions in clubs, and there is this overwhelming feeling that you have to stay on top of all of these things all at once. It’s like a bunch of water balloons are falling and you have to catch them all before they hit the ground and burst,” Cotton said.

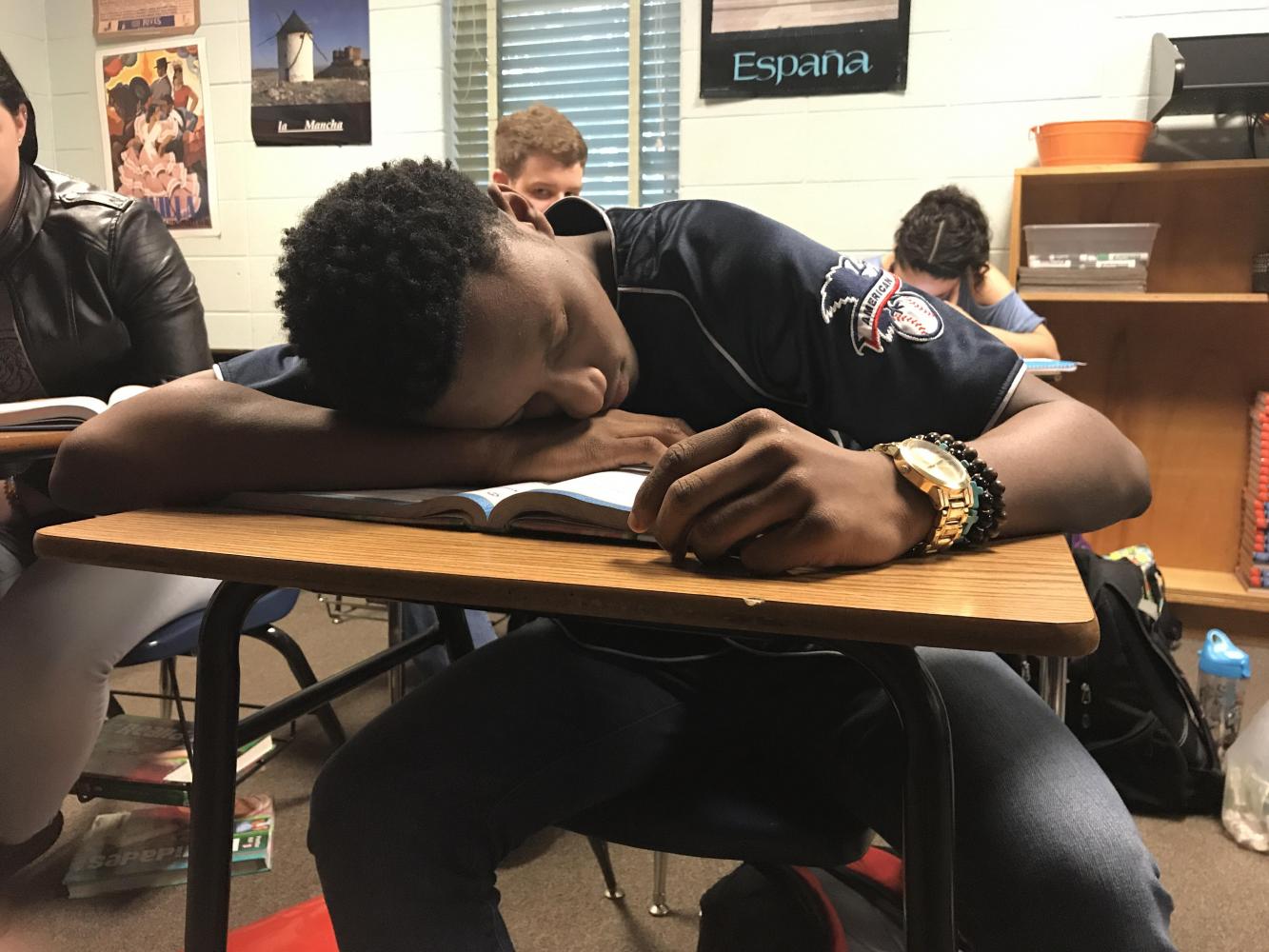

These same students leave the school well after 3:30 p.m. dismissal once they finish practices, games, opportunities for community service hours, study sessions, and more. Finally students arrive home around 6:30 p.m. — for NC Magnet students who live out of district their nights usually start even later due to their lengthy commute home — and do not usually hit the books until 8:00 p.m. after showering and eating dinner. Shortly after starting homework, students’ eyes begin rolling back and their heads and cannot quit nodding off. Some resort to caffeine, jumping jacks, or bright lights when fighting off the waves of exhaustion while others give in and crawl into bed or use their AP U.S. History textbook as a pillow.

High-school student athletes may have it the hardest juggling their sport, school, and social life, while still obtaining sufficient sleep. Research suggests less sleep causes depleted energy, speed, and focus within athletes, lessening their overall performance during competition. Insufficient sleep can also result in an injured athlete, as less sleep means slower and poorer post-competition recovery. NC coaches struggle when working with their scholar athletes in managing their academics and overall health. Involvement in high school sports involves more than simply attending practices and takes a lot out of the athletes who persistently show up each day ready to work, despite the overwhelming fatigue they feel.

“It’s extremely important to get a lot of sleep as an athlete. Also, to be able to function and pay attention in class you must get a lot of sleep. However, it’s really hard to balance practice and getting enough sleep as well as completing all my homework,” junior Abby Jeske, a top-performing varsity runner on NC’s Cross Country and Track team, said.

Aside from excelling in running, Jeske excels in the classroom as a member of NC’s Magnet program. Jeske sleeps around six hours each night on average. She reports feeling weak and more easily irritated when coming off of a week of very little sleep. However, Jeske, along with other NC athletes, prioritizes her studies over sleep because she needs good grades for getting into college. Additionally, Jeske fears feeling lost in class and knows her work will continue to pile up if she does not complete it in a timely fashion.

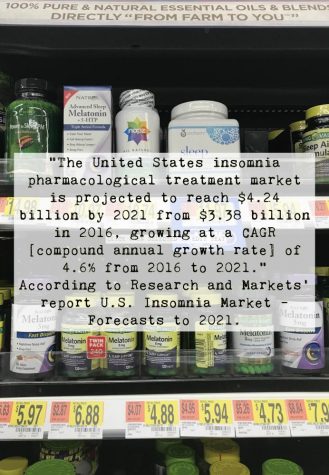

Ultimately, students cannot avoid sleep without facing serious consequences. While extracurricular involvement, good grades, and a social life guarantee an unforgettable high school experience, none of these will satisfy the body’s natural craving for sleep. So long as a sleep-deprived student’s body does not receive adequate sleep, their overall performance and mood will never reach full potential.

The future success of this planet depends on this unhealthy habit amongst today’s teens. Teaching time-management skills will simply not resolve the issue. High school health classes teach students they need at least eight to nine hours of sleep each night. While at the same time all other classes send students a completely different message as they load students with due dates, tests, and material.

Peers share the number of hours of sleep they received the night before like tokens in a game. While students brag about who stays up the latest, they make others view homework as a competition and normalize the idea of sleep-deprivation. Jeske feels like people in her classes brag about who stays up the latest like doing homework is a competition.

By normalizing the issue, individuals encourage and force the habit onto others. While a competitive classroom environment may benefit students short-term, it sends students an unhealthy message. Peers should encourage fellow classmates in prioritizing their own health and lead by example by doing the same for themselves.

Not enough hours exist in a day for today’s students and their busy lives. Students learn the essence of problem solving and thinking ahead in school classes, but application of these skills does not appear outside of the classroom regarding student health.