The last walk

May 24, 2017

Anything Can Happen in the Next Half Hour by Enter Shikari

As sophomore Chloe Vernex-Loset woke up on the morning of February 11, 2015, she got ready for school, checking on her brother one last time before making her way to the bus stop at the end of the street.

Chloe glanced at her brother’s locked door, but she refused to overthink it. She went on, not knowing that she would later remember it as the worst day of her life.

Chloe’s brother, battling years of addiction, took care of her on February 10, 2015 while their mother traveled to Mexico for work. That night, they celebrated his fifth month clean.

“He asked me to go for a walk with him, and I told him I didn’t want to. I will regret that for the rest of my life,” Chloe said.

With puffy red eyes and odd behavior, Zacharie (Zak) Vernex-Loset, Chloe’s 22-year-old brother, exchanged a “good night” and an “I love you” with his sister before going to his room for the night, but despite his promise that he would see her the next morning, Chloe never saw her brother again: he had overdosed.

“When someone dies of something that society considers to be shameful, it’s hard to plan a funeral,” Chloe Vernex-Loset said. “Consider this: you never see teen and young adult drug overdoses on the news unless it’s a famous person.”

Hesitant on whether or not to tell people the true cause of Zak’s death, the Vernex-Loset family hosted a funeral for 300 guests. Ultimately, they decided to confide in their close friends on the events that had truly taken place.

Together, Zak Vernex-Loset’s closest family and friends stood in the cemetery and recited the serenity prayer said at the end of every AA meeting: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the strength to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

Who are you? by The Who

Born in France and entranced by music, Zak Vernex-Loset always loved to play the guitar and write songs.

“He called himself the Fresh French, and he always asked me what my opinion was on his songs and if his transitions sounded sloppy or messy. He’d make sure that it was perfect,” Chloe said. “His music was amazing. And the way his face brightened up when he was making or listening to music was probably one of my favorite things to see.”

However, Zak’s love for music soon grew into something more than just a source of inspiration.

At the age of 13, his obsession with Nirvana and Kurt Cobain, whose songs and lifestyles often promoted drug use, reached a new level when he and his friends began using prescription painkillers to get high. Soon, his painkiller addiction manifested into heroin use.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “Nearly half of young people who inject heroin surveyed in three recent studies reported abusing prescription opioids before starting to use heroin. Some individuals reported switching to heroin because it is cheaper and easier to obtain than prescription opioids.”

Despite the small dip in Zak’s grades, his behavior at home seemed to reflect that of a normal rebellious teenager, and until Chloe entered her last year of middle school, Zak’s addiction remained a secret from most of his family.

“When I was in eighth grade, my sister finally told my parents that Zak had a scary heroin addiction. I was confused; I didn’t really understand most of it. My mother and father kept things really quiet, but I do know that my mother cried a lot and was really scared for him,” Chloe said.

Thereafter, Zak’s family admitted him into a local rehabilitation center, Ridgeview Institute, that aided in his brief recovery.

Ridgeview’s 12-step program gave Zak a six-week period to fully detox and face withdrawals from heroin without the help of any medication created to stop the body’s heroin cravings, such as Suboxone.

In simpler terms, Zak faced the complete repercussions of heroin detoxification without the support of his family: nausea, shaking, agitation, sweating, and depression. He had no access to a cell phone, and the facility only allowed one phone call per day, worrying Chloe to no end.

“A lot of the time, we had no idea what was going on. He felt very isolated and scared because he was going through recovery without us there to hold his hands and tell him we were there for him,” she said. “It made him feel like a prisoner a lot of the time. It really took a toll on his mental health.”

However, Ridgeview provided services for families of recovering drug addicts as well, holding special meetings where families asked questions to better understand the effects of drug addiction through the user’s point of view.

This program, Families Anonymous, created an environment where families could express their concerns and confusion without fear of judgment.

In another meeting offered by the facility, families could ask questions and share experiences without the presence of the patients, making it more comfortable to cite personal situations without throwing their recovering family member under the bus.

“It really helped my family feel less alone,” Chloe said.

Once Zak completed his six weeks at Ridgeview, his family admitted him into another program: Safety Net.

Safety Net, an apartment complex where Zak roomed with other recovering drug addicts and alcoholics, required residents to participate in community service and find a job. By administering random drug tests each week, Safety Net ensured the continued recovery of its residents while they enjoyed a higher standard of living.

“It really seemed like he was doing wonderfully,” Chloe said.

Unfortunately, the Vernex-Loset family never could have known that Zak’s progress and recovery would not follow through.

The Obvious Hidden Clue by The Fresh French

Chloe Vernex-Loset, in her final attempt to contact her brother on February 11, 2015, left him a message saying she arrived at school.

When Zak’s ex-girlfriend began texting her frantically to ask about her brother, Chloe could only give the information she knew: he acted oddly before bed, he locked his door, and he did not answer her calls.

They agreed to meet at the Vernex-Loset house to check on Zak, and when Chloe and her grandmother came home to prepare for dinner, Zak’s ex-girlfriend pulled into the driveway in panic.

Chloe and her grandmother followed Zak’s ex-girlfriend to his room, the door still closed. Chloe’s grandmother picked the lock and peeked inside, immediately and quietly telling her granddaughter to go into the living room.

“I remember [Zak’s ex-girlfriend] coming upstairs in shock, crying and saying no over and over again, and my grandma walked up to me and hugged me, very calmly telling me that Zak had died,” Chloe said.

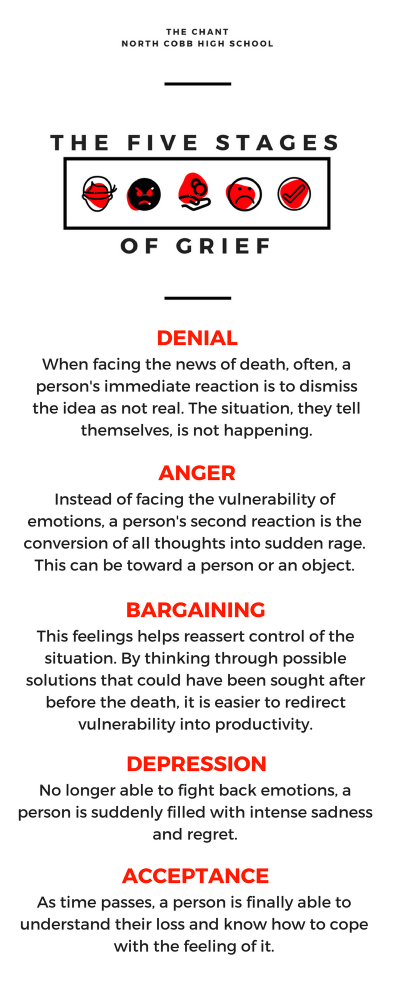

Chloe refused to believe it. She pulled away from her grandmother’s embrace and shook her head. Even when the police arrived, she did not fully grasp the idea that her brother had died.

Zak took a hit of heroin the night before without knowing it also contained Fentanyl. Combined with the effects of the strong narcotic painkiller, the heroin Zak injected caused his body to go into overdrive, resulting in his death.

“It wasn’t until I had to call my father and sister to tell them they needed to come to my house as fast as possible that it really hit me,” Chloe said. “I remember my sister crying as she ran into her car while she was on the phone with me. I never told her he was dead but I think she knew.”

The Vernex-Loset family all began making their way to the house, and one by one, they came in to face the news. Everything still a blur, Chloe only remembers the feeling of anger, panic, and overwhelming grief.

Keep Your Head Up by Ben Howard

From a young age, Chloe Vernex-Loset loved watching her brother make collages. Zak would sit at his desk, cutting pictures out of magazine articles and gluing them together to create intricate patterns. Zak explained his vision to her, telling her how he manipulated the meaning of the shapes to show a different story. Chloe stared, mesmerized by his ability to make art out of random photos.

“I kind of held my brother in this godly status. He was my hero,” Chloe said.

Zak often involved his sister in his pastimes, singing to her and teaching her music techniques as well. And to this day, Chloe recalls the moment she sat on his bed as he performed a private concert for her, singing “Hey There Delilah” by the Plain White T’s and playing the tune on his guitar.

Still, Chloe knows very well that memories fade, and perceptions change.

“My brother was such a beautiful person, inside and out. He was very confident and talented,” Chloe said. “But he was very weak.”

Now, over two years after her brother’s death, Chloe still faces the anxiety and depression following the trauma. She no longer attends Ridgeview meetings, but she visits a therapist to help her recover.

Little moments still remind her of Zak, like a song he used to play or an artist he looked up to, but Chloe knows better than to let those thoughts affect her well-being.

“My favorite song was the one I discovered just after he died. I was on a plane to Hong Kong, and I pulled out his iPod. The first song that came on was ‘Keep Your Head Up’ by Ben Howard,” Chloe said.

To help in recovery, Chloe and her family bought necklaces with Zak’s ashes made into them. Despite the steep cost, the Vernex-Loset family sees the necklaces’ artistic beauty as a symbol of Zak’s personality and vision.

Chloe wears hers everyday, and she knows that Zak would love them.

Instead of dwelling on the past, however, Chloe looks for the positivity in everything she endures, through the opportunity to help those struggling through similar situations or the knowledge that upsides exist in every difficult circumstance.

“The good that came out of my brother’s death was the sudden closeness of my family. We all kind of noticed how important we were to each other and how much we loved each other,” Chloe said.

The initial shock of the situation disappearing, Chloe now expresses her comfort in the idea of helping others who fear for a family member’s health. Recalling her personal experiences, she knows which situations she handled correctly and which she did not.

She takes pride in knowing her grievous situation could potentially prevent her peers from going through the same misfortunes.

“The best way to confront someone using drugs is to make sure you don’t belittle them, judge them, or attack them,” Chloe said. “Try to remember that the things they are doing are because of the addiction. Addicts are selfish because they can’t help it. You have to focus on yourself and your recovery when they are recovering. Whatever happens, it is not your fault. You are not in control of the addict.”

Often, people overlook the symptoms in a family member or friend because of the person’s personality or circumstance, but Chloe urges her friends to think differently.

“Addiction can happen to anyone. It’s not just the homeless guy with scars all over his face or the super rich guy with too much money,” Chloe said. “Sometimes it’s the person with amazing grades and the world rooting for them. Sometimes it’s the person everyone thinks is perfect.”

Regardless of Chloe’s knowledge of what she and her family could have done differently, she also remembers how her brother’s death impacted her positively.

“My brother’s death actually helped me learn to love myself, if that makes sense. I know I won’t ever do drugs. I won’t give up on myself,” Chloe said.

And so, Chloe Vernex-Loset recalls the exact night her brother died, and she knows the single moment she would change in the years of grief her brother’s addiction caused.

“That night, I was the last person Zak spoke to in person, but I never got to see him again,” she said. “That’s the only thing I would change. I would’ve gone for that walk with him.”

Chloe Vernex-Loset • May 24, 2017 at 11:30 AM

Bahaar you rock my world and I love you. You wrote this way better than I ever imagined. I really appreciate you writing about my brother and my experience!