Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

How does a memory work?

December 19, 2017

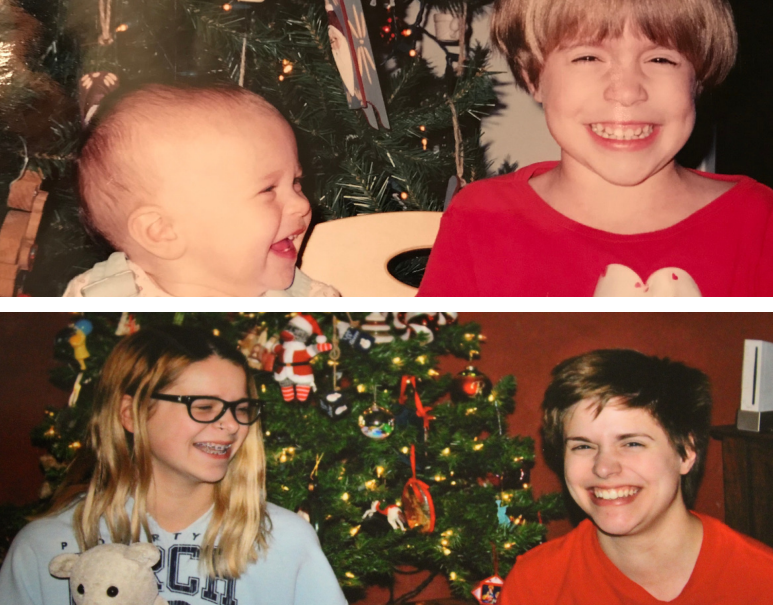

Shannon (left) recreates a childhood memory for her parents with older sister Kayley (right).

As children, we make memories that at the time seem extremely important: the first time riding a bike, the first day of school, and all the other stereotypical childhood occurrences that linger in the minds of young children for years. However, as adults, childhood memories appear to fade, which creates a challenge in trying to recall them. The vivid memories that children remember fade over time due to their underdeveloped hippocampus in the brain.

“It [the hippocampus] intakes all sensory information, with the exception of smell…. It processes new memories,” AP Psychology teacher Melanie Shelnutt said.

The hippocampus ties all of the scattered pieces of a memory, like sound and visuals, together. According to Nora Newcombe of Temple University, children usually fail to remember specific episodes until ages two to four because the hippocampus starts tying fragmented pieces of memories together during this time.

Memories of one’s own birth cease to exist due to infantile or childhood amnesia. Although a concrete answer as to why childhood amnesia occurs still puzzles scientists, a number of theories circulate throughout the world of science. A theory by Sigmund Freud offers an explanation stating that perhaps children forget their birth due to its sexual and traumatic nature. Other theories suggest that children learning language may play a role in the development of memories.

A vital aspect of understanding why humans forget their childhood memories lies in knowing how the brain processes memories. Three separate processes, encoding, storing, and retrieval, all aid in memory formation. Encoding begins with perception using the senses. Each of the separate sensations travels to the hippocampus where all the senses integrate into one experience. The hippocampus decides whether or not the sensory details of the experience possess any strong significance and if they do, it turns into a long-term memory. For a memory to become long-term, electricity and chemicals must encode them.

The actual encoding process starts with nerve cells connecting at a point called a synapse. All the action in the brain occurs at the synapses because electrical pulses carrying messages leap across gaps between the cells. When these electrical pulses leap between cells, it triggers the release of a chemical messenger called a neurotransmitter. Neurotransmitters allow for communication in the brain to occur, and they release from the axon terminal of a neuron and travel to the dendrite of a neuron. After this, the neurotransmitters bind and activate the receptors on the dendrites. When the dendrites receive the message, they reach out to neighboring cells to relay the memory in process.

By cells sending multiple messages to each other, synapses strengthen, which in turn makes the brain’s ability to make connections stronger. With each new experience, the brain slightly rewires its physical structure. Memories form based on input from the outside, so changes in the outside environment cause intricate circuits of knowledge and memory to build in the brain. For example, remembering a piece of music that one plays over and over again will stay fresh in the brain, but if you stop playing that piece of music for a couple of weeks, the musician will find it difficult to play it.

In order for the brain to determine an important memory versus an unimportant memory, the person must pay attention to their surroundings. Daily activities, such as brushing your teeth, taking a shower, eating breakfast, etc. do not create memories because they hold no extreme significance. If the brain remembered every event, it would overload on memory formation. However, the question of how the brain decides the significance of a memory still puzzles psychologists. Scientists do think though, that how a person pays attention to information may aid in memory.

“We have selective attention. There’s no way we can be aware of everything that’s around us, and we miss most of it,” Shelnutt said.

The second stage of memory formation revolves around storing the memory. Scientists believe three stages make up the storage process: the sensory stage, short-term memory, and ultimately long-term memory. During the sensory stage, the senses involved in the memory immediately store themselves into short-term memory. This process lasts for only a brief second due to the brain’s quick ability to register information. Short-term memory can only hold about seven items at a time but only for twenty to thirty seconds.

“Short term memory is about seven items, plus or minus, and you can only hold it for about twenty seconds, unless you can apply it to something already in your brain,” Shelnutt said.

Important information transfers itself into long-term memory, the third stage, where unlimited amounts of memories reside. Scientists believe that in order for a memory to become long-term, it must travel through the sensory stage and short-term memory. For example, when studying for a test, if a student only looks over their notes once, the memory won’t store in long-term memory. However, if the student studies continuously, the retention of the information will increase, which results in a long-term memory.

Storage failure could serve as the cause of infantile amnesia due to immaturity of the inferotemporal cortex and prefrontal cortex. These two cortexes correspond with the improvement on a number of memory responsibilities. Contrary to popular belief, the hippocampus, most active in memory formation, shows great maturity at birth.

Retrieval of the memory serves as the final step in memory formation. To remember a memory, a person must retrieve it on an unconscious level, and bring it to a conscious level at will. The human brain will recall a specific memory with ease when distractions did not present themselves at the time of the event. Forgotten memories occur from improper encoding in the brain because of a distraction.

Another cause of infantile amnesia could lie within the retrieval process because young children cannot access old memories. Growing up alters a young child’s perception to such a degree that appropriate retrieval cues disappear over time. The cues that we affiliated with memories as infants may disappear as our view on the world changes. At infantry, a table seems enormous, but by early childhood a table may not seem so large to the child anymore. The same idea applies with this theory; as children grow, they outgrow their old memory cues, making the retrieval process nearly impossible. Connection to old memories will cease to exist as long as the child grows.

“The physical structures needed in the brain for long-term memory aren’t formed until ages three, four, or five,” Shelnutt said.

However, not all forgotten memories fade from just suppression or repression. For children, childhood amnesia strikes early, most times before the age of ten. According to National Public Radio, a conducted study observed children at the age of three recalling a recent event in their life, perhaps visiting an amusement park or a relative visiting. Researchers found that by the age of seven, more than 60 percent of these children could recall the memory they spoke of at age three, but by eight or nine, less than 40 percent could recall their memory.

Memories that tend to persist throughout childhood into adulthood typically caused emotional distress to the child. Emotional memories tend to stick around because they “scar” a child for life. A study conducted by Patricia Bauer on mice revealed that an increase in emotional stress leads to a chemical change in brain receptors; the change strengthens connections in the memory regions of the brain. Because of the strength in connections, the emotional memories tend to stick around in the brain for years.

“The bad memories you have in life… you’re gonna remember them more clearly than just regular stuff that happens everyday because the stress hormone, cortisol, solidifies long-term memories,” Shellnutt said.

The age of seven proves the most likely age for children to start recalling memories accurately due to similarities to the brain structure of an adult. A young child may only remember certain parts of a memory. For example, they may only remember the “who” of the memory but not the when, where, or why.

“In kindergarten, I had this friend named Timothy, and his mom worked at my elementary school. He had asthma, so every single day during lunch I would walk him to his mom’s classroom, so he could use his inhaler,” junior Shelby Ruhl said.

Ruhl’s memory may come from the function of an underdeveloped adolescent brain, but it sticks with her due to the emotional aspect connected to it. The connection she held with her friend made the experience memorable to her, so she can recall the memory in full detail today.

Although scientists and researchers know a significant amount of information about why first memories fade, pieces of the puzzle still lack. The question of why birth memories don’t stick around challenges the idea of traumatizing events staying with a person until death. Research indicates childhood amnesia not as a case of “normal forgetting”, but as a strange phenomena that does not occur in adults. Adults forget information over a linear function of time, yet studies show that between birth and early childhood, children forget more experiences than expected by the adult forgetting curve.

Theories, such as the storage and retrieval failure ones, seem most logical, but another theory emerged over the last twenty years, called multiple memory systems. The theory suggests memory as not a single entity but made up of multiple distinct brain systems. The two systems, declarative and nondeclarative memory, differ greatly. Declarative memory pulls memories from a conscious recollection of experiences, while nondeclarative pulls from an unconscious memory of skills and abilities. The unconscious memory system appears at birth, but the conscious memory system develops over time. All signs point to the multiple-memory system approach to infantile amnesia

Even though psychologists know a great deal of information about memories and why they fade, just like most bodily functions, there still remains undiscovered information. However with the rising support for the multiple-memory system, scientists may finally unravel the complex mystery of childhood amnesia.

Anita Swiderski • Dec 29, 2017 at 10:39 AM

This article is fascinating and informative. The editor is spot on.