Racism in public schools: How Cobb and Greater Atlanta desegregated with racist elements left behind

December 2, 2019

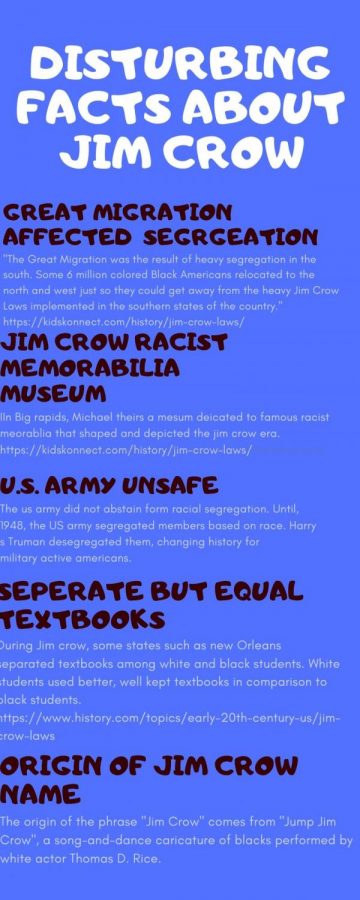

Racism, although legally abolished, remains a sensitive topic among Americans, dominating the cultural and social implications of today’s modern society. In public facilities throughout the United States, Jim Crow Laws once ruled in favor of the famous term “Separate but Equal”; depicting racial inequality at its peak. This doctrine majorly influenced the South, infusing chaotic hatred and violence within the southern culture. Now as today’s world lives as an integrated democracy, the issues that remain prominent including racism, become an important issue to discuss and further educated the current generations. Within the modern society students as well as parents and teachers should educate themselves on the issues to better understand how their local schools and facilities once existed as segregated white supremacist institutions and the reasons behind why modern discrepancies and issues still exist today.

“In the South, ‘Separate but Equal’ meant that legally, people can separate and keep a white society in the south and black society in the South, with whites as superior. However, the problem relied on the lack of inequality. They displayed the separation part correctly, but not the equal part,” NC Honors World History and Ethnic Studies Teacher Scott Trepanier said.

The term “Separate but Equal” began in 1896 during the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson. In a unanimous rule, the U.S. Supreme Court instituted racial segregation (Jim Crow Laws) within all public facilities, such as water fountains, bathrooms, public schools, etc.

“Because the south was against integrating it has really affected our society today because it makes people think that everyone they come across is just going to harass them and make them feel bad but others feel that respect is expected for everyone because for me I expect that people will be polite to each other and put aside those differences and really get to know each other through our personality.” freshman Victoria Sorrell said.

Georgia, and more specifically, Cobb County strictly enforced these laws, feeding the harsh, racist rituals of the south. Looking at Georgia’s public schools, segregation reigned, as the division of African American schools and Caucasian schools took place among students.

“In Cobb County at that point, there were only a few high schools and if you were a minority student, you had to go to a minority or ‘Black Only’ school in Marietta,” Trepanier said.

With efforts to change public school segregation, the 1954 landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v. The Board of Education stated that legally segregating African Americans from Caucasians students contradicted the constitution. Defense attorney, Thurgood Marshall, standing in front of all nine justices, explained how legal segregation in the public school system, violated the “equal protection clause.” Once passed, it ignited a fire in the hearts of Southerners, with persistent resistance to the new law.

“What Brown does is it forces states over time, to integrate their schools so that all schools would be open to any student that attends their district. In Cobb County, for example, there were white schools and black schools. After the Brown decision, NC opens in 1958, as a fully integrated school because the decision had been in place for long enough that anyone could attend, ” Trepanier said.

In retaliation to the Brown decision, Georgia’s governor at the time, Herman Talmadge proclaimed that any school district that attempted to desegregate would immediately lose all state funding, forcing the schools to close. This concerned Georgians, especially Cobb County and Atlanta public schools.

Looking at Cobb County, citizens felt conflicted, halting Cobb’s student integration. Although NC opened as an integrated school, the rest of Cobb remained undecided and as a result, it would take another six years for Cobb to institute integration. At the time, Cobb School Superintendent, Paul Sprayberry, asked all students and staff to remain “calm, patient and resolute,” basing their concerns less on desegregation and more on the idea of shutting down schools and losing funds.

In regards to Cobb’s stall, the Cobb Chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) sent letters to both the Cobb and Marietta school boards asking that they detail their plans for complying with the Supreme Court’s order in January of 1960. Cobb County felt the overwhelming pressure, a factor that would influence their decisions.

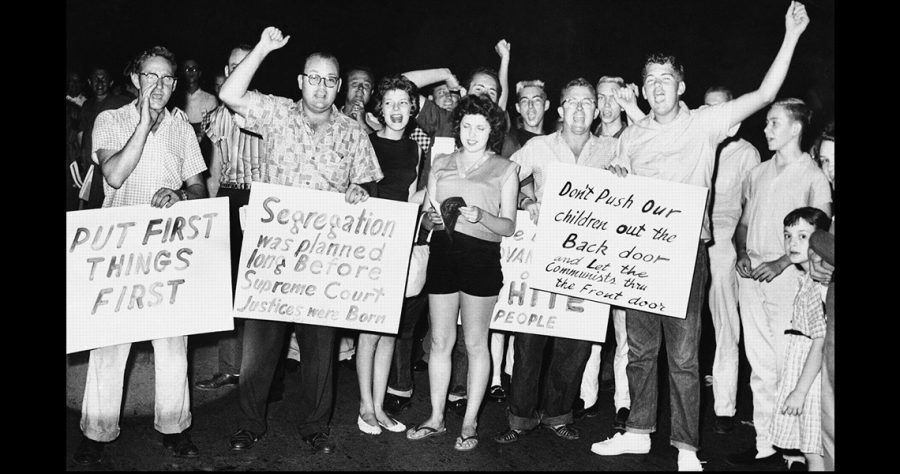

In addition, the Cobb County White Citizens for Segregation gathered at Sedalia Park Elementary School to generate a strategy for pressurizing both the public and the school boards to oppose the new law permanently in March of the same year. The group proposed a boycott using the slogan “Trade at the Store with the ‘S’ on the Door” and publicized the boycott in two full-page ads in the Marietta Daily Journal. This wreaked havoc, heightening Cobb’s difficult decisions.

After the chaos and pressure on Cobb, the Cobb County Board of Education voted five to one in favor of desegregation on March 1, 1965, only one year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. In the next five years, desegregation would become a complete reality.

“I would say that the majority of Cobb County integrated well overtime. It definitely still experiences issues in certain schools, but overall the student body, especially at NC remains diverse,” freshman Claire Scfadi said.

Although Cobb slowly integrated, greater Atlanta’s integration quickly became a reality. Public universities in Georgia, such as the University of Georgia, soon integrated as early as January of 1961; four years before Cobb. African American student and UGA integrator Charlayne Hunter applied to UGA with high hopes in the summer of 1959. She soon received a letter telling her the dorms were full, a nice way of saying “we don’t allow your race at our campus.” Although a discouraging response, Charlayne fought tooth and nail to eventually integrate the school after 160 years of segregation. After her efforts, she invited students of the Atlanta nine, giving advice and providing safe ways to desegregate their local public high schools.

“ The integration of UGA was really beneficial. It kind of set an example for all of the schools in Georgia to take that step and really be confident that people can put aside the differences and learn to love each other for who they are,” Sorrel said

Soon following, the Atlanta Nine, entered four all-white Atlanta Public high schools (Brown High School, Northside High School, Grady High School, and Murphy High School, now Crim High School) permanently desegregating them on August 30, 1961. During the events, parents of the nine students received severe threats and abusive phone calls resulting in police patrolling at each student’s home. Although concern for the students’ security, the students remained safe going on with their high school careers.

After Cobb and Greater Atlanta’s reluctant efforts toward school integration, the elements of racism began to linger leaving behind a growing racist culture that implemented itself into the 21st century. Now living in 2019, the elements of racism in some instances, still implants itself in Georgia schools including Cobb County.

“Today it seems as though most people see our color as a weapon and feel as though they have to use excessive force with us. But if it were a white student they would use the mental health card and just have a talk with them. Racism is still prevalent today and wonʼt go away if we donʼt come together,” junior Hanniyah Grimes said.

The common concern of disciplinary action still haunts in terms of equality. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, an AJC investigation found that African American students made up about 67% of expelled or suspended students in Atlanta public schools, In 2014. This generates concern among parents and students raising the question- Do African American students experience an increased amount of disciplinary action in comparison to white students?

“I don’t know if African American Students are more prone to discipline…In my classroom, I don’t really see a difference between students in terms of behavior, but anything is possible. It’s one of those situations where some schools experience those problems and others don’t,” Trepanier said.

Another factor relies on the distribution of races, implying that the term “Separate but Equal” never fully left the United States. In an article done by NYTimes, more than half of the nation’s schoolchildren exist in racially concentrated districts, where over 75 percent of students are either white or nonwhite. Georgia, in some areas, experiences this problem, including Cobb County.

“I think Cobb does a fairly good job of bringing students together, but there are still challenges because some schools are primarily-minority schools, particularly the southern end of the county. It’s a different environment for those students than east cobb schools where its a majority of white students,” Trepanier said.

Although Cobb still in some instances deals with this issue, the issues don’t carry out in NC’s culture.

“I attended Ford Elementary and Lost Mountain Middle School, both Cobb County schools and I have to say, the student body of both schools was primarily caucasian. I am extremely relieved and very pleased that NC’s culture and student body is diverse. Although throughout Cobb county diversity in some schools including mine remains an issue, NC definitely lacks this problem,” Scafadi said.

Despite the fact that racism is still present within public schools, the overall integration of schools evidently shows growth post-Jim Crow. The element of racism Jim crow left behind, although severe in some instances significantly decreased after the desegregation. The question now: What does the future look like for Georgia and for public schools in terms of race? Time will tell.