Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Sweatpants or Sweatshops: How our desire to keep up with trends impacts underdeveloped countries

December 12, 2019

When buying a new outfit from the store, the majority of apathetic young people do not concern themselves with the origin of their clothes. Instead, pricing, quality, style, and color flood their thought processes before checking out. At one point or another, an individual may experience the thought-provoking question of where their clothes come from and the identity behind who produced the garment. The clothes that high school students wear mainly revolve around what society views as trendy. The entertainment industry heavily influences these fashion choices for young adults, thus encouraging the increase of clothes in high demand in order to fulfill the needs of retail industries.

“I like to go shopping every week if time permits. Prior to this school year, I did not look at the tag to figure out where the clothing came from. This changed once I read The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy in my AP Macroeconomics class. After reading this book, I have become more concerned about where my clothes come from to try and avoid clothing that could have come from a poorly managed sweatshop,” magnet senior Precious Ajiero said.

The term fast fashion defines trendy inexpensive garments that first appear in the modeling and celebrity world then transform into a cheaper quality and sold to the general public. Major retailers that participate in the fast-fashion concept include Forever 21, H&M, Hollister Co., and Abercrombie & Fitch. These companies and others like them, revolve around the production of clothes at a high quantity or bulk, while maintaining cheap production costs to increase their own revenue. In order to achieve this system, the companies stated prior produce their clothes in sweatshops.

Sweatshops, a concept that first appeared in American culture on the east coast in the late 1880s, provided a workspace for African slaves and immigrant workers. The inadequate work conditions of the buildings forced workers to complete harsh and extensive shifts only to receive little to no pay. Workers not only faced severe environmental conditions but also faced the potential risk of contracting diseases due to improper health code standards. These individuals became obligated to work in areas with massive, faulty machines, hazardous chemicals, unsanitary bathrooms, abnormal temperatures, and allergenic substances.

“These buildings are not fair for the employees because their effort is very underappreciated and they are not getting the benefits or rewards that they truly deserve from their work” Hiram High School freshman Janaya Evans said.

The makeup of sweatshop workers include 85% of women who fall between the ages of 15 and 25. Companies that own these sweatshops located in third world countries monitor their women closely, ensuring that the women take pregnancy tests regularly to reduce and prohibit individuals from receiving pay for maternity leave. These women endure both physical and verbal abuse in a high-stress level environment to reach their quota for the set day.

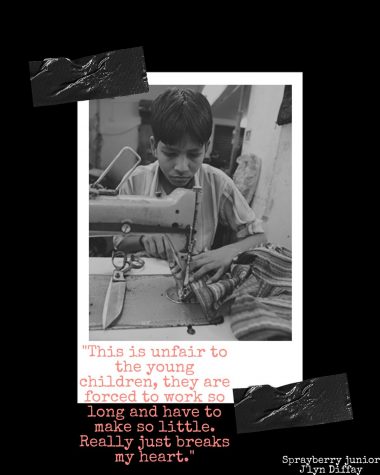

The remaining percentage that typically makes up sweatshops in underdeveloped countries include children, both boys and girls. Child labor, although banned in the United States, remains prevalent in continents such as South Asia, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa. These children work 45 hours per week in hopes to help support their families with the low-income rate. Their efforts cause multiple problems, the time that a child spends in these poor conditions removes them from the average childhood experience, thus distorting these individuals’ mental states as they mature into adults. Work becomes the only concept they know, while leisure, freedom, fun, and enjoyment remain unfamiliar subjects to children. Young individuals that work full time in these sweatshops also miss out on their education. In Bangladesh, an estimate of 1.5 million children never enrolled in school and instead 1.3 million work full-time shifts to only receive .05 to .20 cents a day.

“To be quite honest, I did not know what sweatshops even were and I definitely did not know that they had kids as young as five years old making items that we throw on and take for granted every day. This is unfair to the young children, they are forced to work so long and have to make so little. Really just breaks my heart” Sprayberry junior J’lyn Diffay said.

In 2013, the impact of these poorly maintained shops resulted in a fatal incident in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The Rana Plaza, a fabric building that collapsed, and killed 1,129 people became a striking wake-up call to clothing factories to change their safety protocols. Walmart however, a U.S based company that relies on the production of their products from Cambodia, refused to sign the Accord on Fire and Building Safety after workers complained that they experienced sweatshop-like conditions and worried about their safety after the Rana Plaza incident.

Popular companies such as Gap and Nike recently gained negative attention from the general public, resulting in an investigation on the source of their products and condition of their factories. These companies, who advertise to younger audiences must constantly adapt in order to keep up with the trends and styles that draw teenagers’ attention. In order for the labor abuse cycle to end, teenagers can help by buying eco-friendly clothes. New companies such as Goodfair sell the same trendy clothes that reside in stores such as Forever 21 and H&M without using sweatshop like conditions or leaving a major carbon footprint like their competitors. On their website Goodfair states, “Fast fashion has created a demand for low prices which has forced production to be farmed out to sweatshops. At Goodfair we don’t make anything new—cutting down on the need for low wage factories across the globe.

The issue of overworked individuals and inhumane work conditions will only continue if the general public do not realize where their clothes originate from and everything that went into making the garment. In today’s changing generation, young individuals possess the ability to change labor abuse in third world countries by changing the way they shop.