Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Chicano Power: stories of Latino involvement in the nationwide fight for race equality

December 20, 2019

Students taking any type of history class in the United States can obviously see that the majority of the main historical figures, events, etc. taught, deal with people who fall under the “straight, white male” category. For years, minority students asked for change and more representation in the curriculum presented in schools across the country. People of different backgrounds fought, and continue to fight for this country to become a better place but the history taught in schools erases their presence or depicts them as unimportant.

Although Latinos/Hispanics make up the largest minority in the United States’ population with 18%, students only learn about one piece of what they accomplished in this country. Schools teach a brief section about activist Cesar Chaves and move on, leaving the rich history that one can find in the Latino civil rights movement forgotten, and erasing the oppression faced and resistance created by Latinos during that time.

The Black Civil Rights movement in the south and the Latino Civil Rights movement in the west, also known as the Chicano Movement, echoed one another in myriad ways. They both inspired each other and experienced most of the same things, however, the Chicano movement remains overlooked or forgotten, making the link between them disappear over time. The desegregation of public establishments, such as schools, exemplifies this.

When asked about desegregation and what started it, people usually think of Brown v. Board of Education, when in reality, seven years before that a group of Mexican parents, specifically The Mendez family, took action. In California, cities were segregated towards Mexicans and Mexican-Americans but in comparison to the segregation of African-Americans, people with a lighter complexion or an Anglo-Saxon or European sounding last names were allowed the use of these establishments.

Schools in some parts of California segregated Mexican children from white children. They claimed that they fell under special needs criteria because of their inability to speak English and they intended to prepare them for American education. The problem became that whether or not they spoke English, school officials would sort them to these schools just because of race. The Mendez family moved to Westminster, Southern California in 1943. Gonzalo Mendez asked his sister Sally to enroll their children at the school they were supposed to attend.

When Sally Mendez tried to enroll them, the school told her that they allowed her children to attend because of their lighter skin tone and Basque last name, but Gonzalo’s kids would attend Mexican school. When Sally told Gonzalo, he became furious because the last school his children attended had no problem and allowed them to receive their education alongside white children. Gonzalo, along with four other Hispanic fathers (Thomas Estrada, William Guzman, Frank Palomino, and Lorenzo Ramirez) went to court and challenged Mexican school segregation.

In 1945 the case came to a conclusion in which the state overturned the law that allowed segregation, causing a ripple effect in the whole state. Laws that segregated Japanese-American and Native American students were soon after “abolished”. Mendez v. Westminster set a base for the Brown vs. Board of Education case and created a tremendous impact in American history yet never received the credit it deserves.

The Chicano movement began in 1848, right after the U.S.-Mexican war when the current border between both countries was created. Mexicans living in the new U.S. states were discriminated against in their own land. The movement gained momentum after WW2 but reached its peak in the 1960s and 70s. Throughout the west side of the United States, Mexicans and Chicanos demanded fair treatment in the fields, political/voting rights, equal education, and restoration of their ancestors’ land.

The American agricultural industry, in the past and present, heavily depends on mostly Latino labor. Though they contributed greatly to the stability of the industry, farmworkers had terrible working conditions. Growers, who were the people that owned the land and company these people worked for, paid them $1 per hour, did not provide them with restrooms, and only gave them a single can of water where all workers would have to share from.

Filipino farmworkers faced the same injustices and started a strike, led by Larry Itiliong, way before Chicanos did and by the time it arrived in Delano, California, Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, founders of the National Farm Workers Association, were gathering its members to decide whether or not they would join these protests.

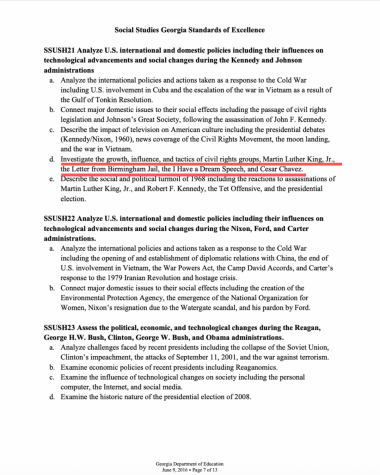

They agreed and shortly after put everyone to work. Strikers would stand near fields of workers and shouted for them to “Stop working”. While there were workers that followed along and left their jobs, a majority of them stayed in place in fear of losing their income. To try and advert this, growers would use loudspeakers to block out the protests so their own workers would not hear them. The movement requested the aid of more people to help end these work conditions but even though vast amounts of people arrived, the impact these strikes were creating barely scraped the surface so they decided to use a different method. Inspired by the Montgomery bus boycotts, the farmworkers started their own by boycotting Schenley liquor. This started to get the attention of various people including Robert Kennedy, who flew down to California to see the events unfold and endorsed the movement. The Farmworkers planned a pilgrimage from Delano to Sacramento, California’s capital, to pressure the government and growers into finally answering their demands for better conditions. This pilgrimage which was almost 300 miles lasted 25 days and by the time they arrived in Sacramento, Schenley gave in and was open for negotiations.

The movement did not see enough improvement after its first year so they turned to boycotts again and since those boycotts did not do as much as activists thought they would people began to consider violent protests. To prevent this, Chavez took a 25-day fast which caused more members to join the union and the talks of violence disappeared. After the assassination of Robert Kennedy, Huerta and Chavez decided to double the effort the union was putting forth. The union sent people to over 40 cities in the U.S. and Canada with one mission in mind, to boycott all grapes until a change was made. Picketers protested in front of supermarkets 12-13 hours a day to expose consumers to everything regarding the farmworkers’ mistreatment.

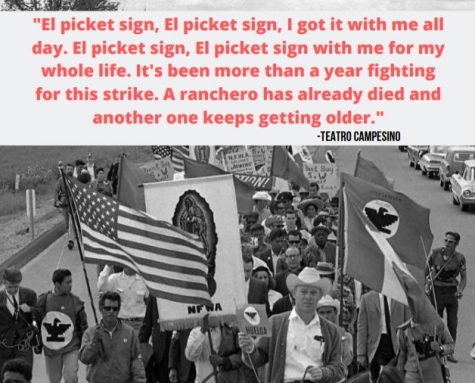

These are the lyrics from the song “El Picket Sign” by Teatro Campesino. With the Chicano movement growing in size, great amounts of people contributed, however, they could. Music became a major way people showed their support.

The boycotts pressured supermarkets and the number of picketers multiplied. Thousands of people followed, from high school students to priests and nuns, a significant amount of Americans joined the protest and it was estimated that 17 million people stopped buying grapes causing a loss of $25 million. After the Coachella valley growers endorsed the movement, people started to purchase only grapes that had the union black eagle. On July 29,1970, growers succumbed and agreed to sign a series of contracts in which they met the workers’ demands and provided them with new resources almost instantly. After five years, their constant fight finally paid off.

Numerous issues made up the goals of the Chicano movement and while the majority benefitted the Mexican-American community as a whole, one major group was often left out. Women in most cultures around the world are mostly seen as housekeepers, child bearers, etc., and Mexican culture was no exception. Throughout the movement, women realized that they did not benefit from the changes as they faced their “prescribed” role in the family.

Chicanas and other women of color criticized second-wave feminism for their inability to include classism and racism into their political coverage which lead to the creation of a sub movement within the Chicano movement known as Chicana Feminism where they started to fight for their rights as women within and outside of their own community.

The majority of schools, textbooks and, sometimes teachers throughout the United States include the Latino civil rights movement in a very minimal way. “We look at standards and clearly it would fit in U.S. History and it is part of our curriculum but its very brief. Other Cesar Chavez there isn’t a ton of specific standards but based on the timing of the End of Course test there sometimes isn’t an opportunity to investigate it further. Said N.C. Social Studies teacher Tom Callahan.

“We have some materials like D.B.Q.s (Document-based questions) and documentaries that go along with it but in some semesters we don’t have enough time to include it. It certainly should be included with the unit in the social change of the 60s.”

This leaves many students frustrated since they don’t get to learn about what their ancestors did for this country.

“I feel like in our educational system we tend to turn a blind eye to situations like that. They tell us that we are taught history so we don’t repeat mistakes, but how are we supposed to learn if we are not being taught about these situations. We are not using history in the correct way.” Magnet Junior Yamille Farias said.

As time moved on, the image of the American people changed and continues to diversify, and students merit a curriculum that reflects their diversity.