Selective shades: colorism’s grasp on Asian communities

May 22, 2023

Asia, home to diverse and vast populations, faces a prevalent issue within its discriminatory standards based on the darker color and shades of individuals: colorism. In a continent where brown skin commonly exists, the desire for light skin plagues Asian societies. Seen through media and generational notions, fair skin as the beauty standard remains openly visible to the public eye with roots dating back to century-old instances. Parallel with this issue comes the harmful prejudices and stereotypes affecting people’s daily lives to the rise of economic businesses that profit millions from these damaging preferences.

Colorism in Asia remains rooted in the history of economic classes and the result of colonialism. Due to long laborious hours under the sun, the working class differentiated from the wealthy with their darker complexions. The wealthy and the upper class did not work outside in the blazing sun, sporting a lighter complexion in this instance. Due to this difference, the link between darker people to a lower socioeconomic class and the stereotypes within the class formed as well as the association of wealth with lighter skin. This desirable trait of wealth and high social standing also creates the desire for light skin. Colorism’s prominence happens in countries such as India and the Philippines, where colonialism has occurred and the effects of colonial rule play a part in instilling long-standing colorism standards in countries. Traces of colonial rule persists in Asian countries, which can result in the idea of continued inferiority toward colonizers long after they have left. The result of this inferiority leads to the desire for lighter skin to fulfill their colonial counterparts. During Britain’s colonial rule over India through the years of 1858 to 1947, the colonial power used a system to categorize the Indian people by skin color and occupation. White Europeans stood at the top of the hierarchy and darker Indians stood as inferior people. Furthermore, Britain used this system to determine which Indians would receive high-ranking opportunities, which included government and white-collar positions. Other British colonies worldwide took part in this system where colorism still stands today. These associations between skin color and wealth or socioeconomic standing prompted the preference for fairer skin to hold the same traits as the wealthy and higher classes.

Preferring lighter-skinned individuals over dark-skinned ones takes place in the entertainment industry as well. Within Asian shows and movies, dark-skinned actors rarely take the screen. In India’s entertainment industry, Bollywood, dark-skinned actors play villains and light-skinned actors play heroes and protagonists. Bollywood’s reputation for casting the majority of light-skinned actors promotes the characteristic of light skin in audiences and the Indian population. This lack of variety in entertainment industries further creates a desire to fulfill these unrealistic beauty standards.

These similar traits find themselves within Asian representation in the American or Hollywood industry. Although Asian representation increasingly makes its way to the big screen in American entertainment, dark-skinned Asians remain left behind to make their marks in the media as compared to their successful light-skinned counterparts. The ground-breaking film “Crazy Rich Asians” made its mark in Hollywood with its majority Asian casting. Though this development made a step toward the inclusion of Asian actors, the film shows traits of colorism similar to the ones presented in Asian culture. Light-skinned Asian actors made up an overwhelming majority in the film while the scarce amount of darker complexion actors available played roles as maids and service roles.

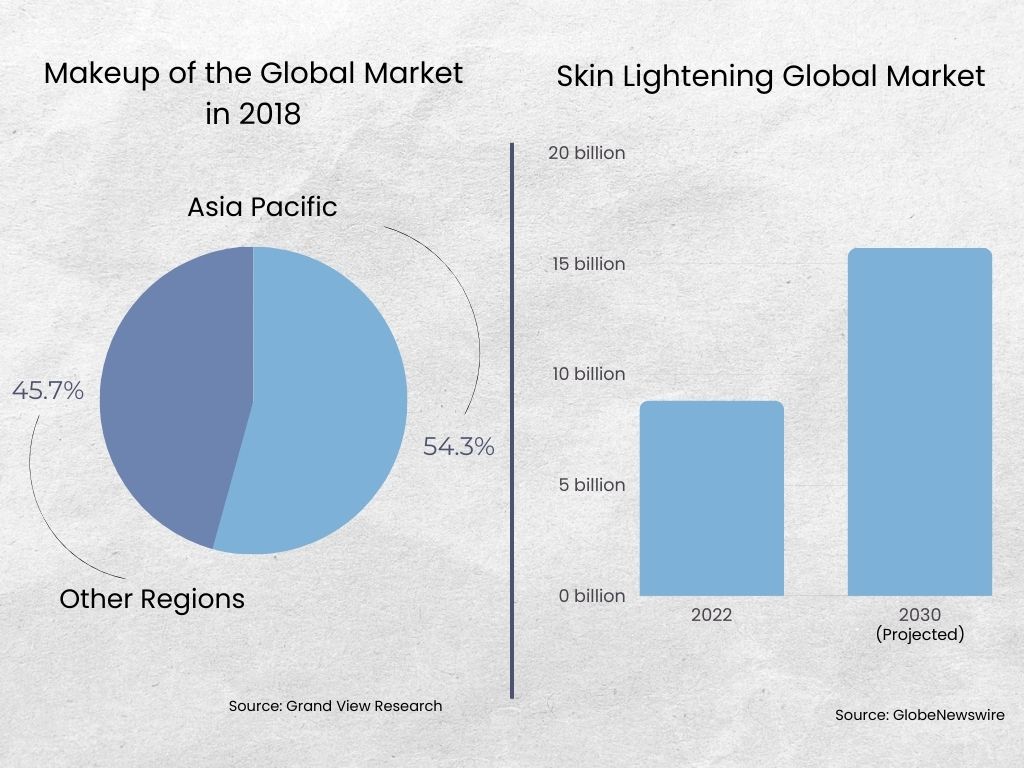

As colorism persists in Asian society, the skin-lightening industry capitalizes off the fair-skin beauty standard and continues to expand in billions. The Asian market makes up the majority of the industry’s global market as of 2017, serving as evidence of capitalization’s success. In 2017, the global skin-lightening industry was valued at $17.9 billion and economists projected the market will grow to $31.2 billion by 2024.

Lightening products remain popular within South and Southeast Asian countries— where the roots of colorism persist in society. Companies advertise that their products offer a solution for Asians of darker shades to achieve a lighter complexion. Major skin lighting companies include Procter & Gamble, Shiseido, Beiersdorf and Unilever, as their products such as lotion, sermons and cleansers stock up on store shelves. Companies have begun rebranding themselves by removing terms of words such as”fair”, “whitening” and “lightening” on their products but continue to sell the products to the public. They simply removed the inherent anti-darkness selling point.

“When you go to the drugstores or the groceries, you will really feel like skin whitening is the way to go because 95% of the lotions are skin whitening and the models are light-skinned women,” Filipino-based social media content creator Trish Terrado said.

Throughout the decades, these same companies have promoted the process of lightening skin within their advertisements and marketing campaigns, geared toward women who primarily use skin-whitening products. Tactics include light-skinned models plastered on billboards and commercials who advertise the effects of the products, giving them that lighter shade. Commercials create scenarios with women that gain the ability to obtain their dream job by becoming lighter. For example, in Priyanka Chopra’s 2008 Ponds ad, a dark-skinned actor earns her lover back after using a product that gives her a “white glow”. These marketing tactics push the insecurities of dark skin with comparison of people with lighter shades and offer a solution to “problems” that dark individuals face which contributes to the notion of favorable fair skin.

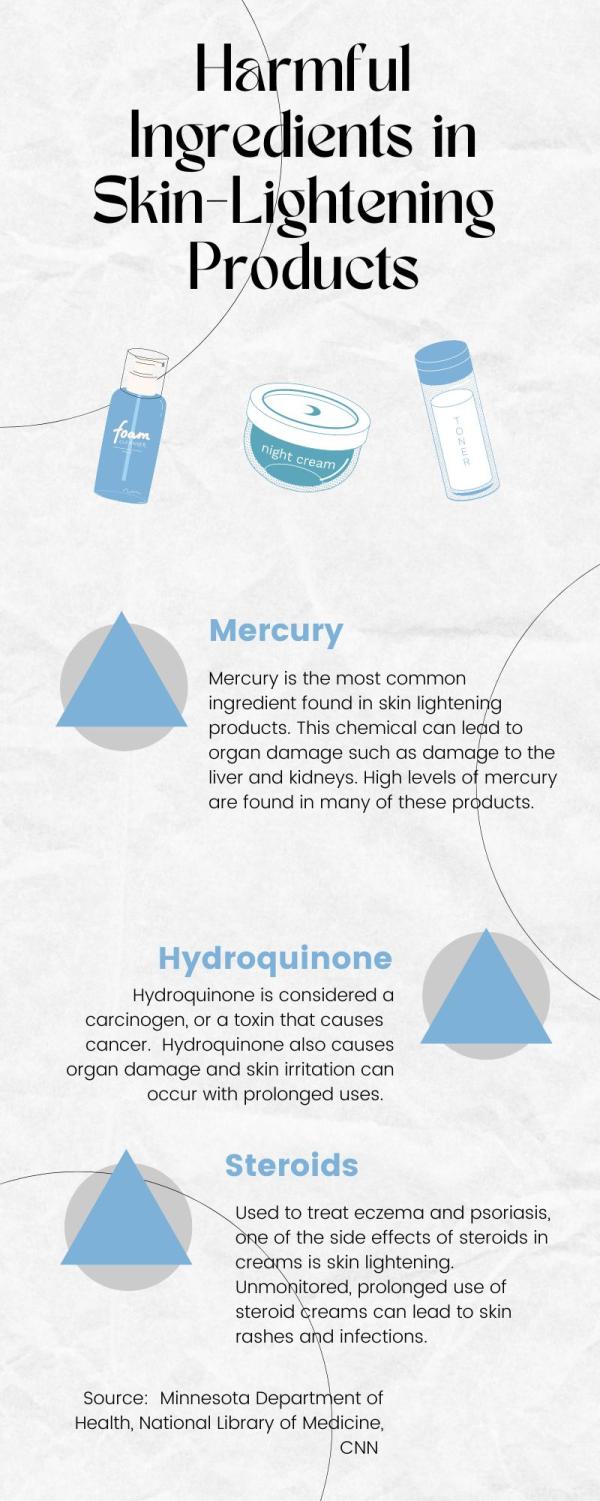

Harmful ingredients in whitening cosmetic and beauty products have not stunted their demand. Doctors have expressed the impossibility to lighten someone’s original skin color but efforts continue. The World Health Organization (WHO) released a report stating numerous skin whitening products contain mercury and other hazardous chemicals that pose harm to health and cause damage to kidneys and the nervous system. Even as countries implement bans on particular products, the companies still find their way to markets through the internet or illegally. Medications that contain steroids and hydroquinone require a prescription in some countries but remain misused or acquired illegally due to their potential to lighten skin. Lack of regulation and misuse of these chemicals can result in potentially serious health problems.

“The bottom line is that skin bleaching products that consumers are purchasing online and overseas may not be safe. In some cases, ingredients aren’t listed on the package, which should be a big warning sign to stay away.” American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) board-certified dermatologist Dr. Seemal Desai said.

The ideology of preferring lighter skin takes place intergenerationally and ingrains itself in communities. In addition to the outside conceptions of preferring fair skin through media, direct influences from family members’ remarks and circulation of skin whitening products in homes further put pressure on people, especially youth, to obtain lighter skin. Bridgerton’s Charithra Chandran spoke of receiving colorism comments from extended family members as well as strangers on her darker complexion. Comments included “shame about the color of her skin” and a comparison of her skin to lighter family members that occurred in her childhood.

“No one let me forget that I was dark-skinned growing up. My grandma was very light-skinned. Whenever we’d go around in India, they’d always say, ‘Oh, you’d be pretty if you had your grandmother’s coloring.’ ‘Shame about the color of her skin.’ ‘She’s pretty for being dark-skinned.’ All of these comments, all the time. My grandparents — I don’t hold this against them at all, they were trying to make my life easier — I wouldn’t be allowed to play outside. I’d have to play early in the morning or in the evening [to avoid the sun],” Chandran said

Preventative measures to stop tanning from the sun remain pevalent within Asian populations. Evidence exists with wearing masks and covering oneself in heavy clothing despite the hot and humid Asian climate to combat sun exposure. These tactics become instilled in Asian populations as younger generations can fear playing outside in the sun due to criticism of becoming dark and subjected to colorism and its beauty standards from an early age. Furthermore, family members and communities encourage the use of skin-whitening creams for a “beautiful” appearance.

“Well, I think that [colorism] especially affects Southeast Asians, West Asians and South Asians, because we typically have darker skin tones. Our [Asians] mental health is affected negatively because like our own family will be making fun of our complexion and like kind of make us think that we are less beautiful because of a darker complexion and then also like your own people, not finding us attractive even like in the like Asian world even and in the Western world,” magnet sophomore Elijah Smith, co-founder of NC’s Asian Student Association said.

Chandran’s experience resonates with other dark-skinned Asians as stories of bullying and discrimination from peers and family members for their skin shade become continuously shared and bring attention to the issue. Addressing Asia’s colorism comes through the forms of hashtags and media movements. One movement began with the #MagandangMorenx, as Asia Jackson, an LA-based actor of African American and Indigenous Filipino descent, challenges traditional beauty standards of fair skin with the promotion of the hashtag that translates to beautiful brown skin. Global media campaign “Unfair and Lovely”, which contrasts the widely used popular skin-lightening brand “Fair and Lovely”, became popular on social media in 2016. The campaign invited dark-skinned individuals to post themselves, combatting beliefs regarding colorism by showing the beauty of their darker shades.

Changing long-standing beauty standards can seem like a challenge, but taking steps can change the outlook on how people view darker complexions. Colorism’s intergenerational source continuation to pass through communities and families could end. Representation in the media can show dark-skinned Asians taking on roles contrary to their stereotypes. Putting an end to these beauty notions can create a safer, healthier outlook on diverse, colorful shades out in the world.