Suffering or salvation?: A universal guide to Lent

April 12, 2016

Every year in February, Christians, specifically Roman Catholics, across the world embark on a trial of suffering and fasting for approximately forty days: Lent. The fast, which mirrors the forty days Jesus spent in the wilderness tempted by the Devil, asks patrons to abstain from an aspect of their lives to prepare for the crucifixion and ultimate ascension of Christ on Easter. As a Catholic since birth, I asked junior Bethel Mamo, a non-Catholic Christian, to try participating in Lent for the first time and compared our experience to see the effect of the 47 day-long fast.

A History of Suffering

The Catholic (also celebrated by some Methodist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, and Anglican churches) holiday of Lent starts on Ash Wednesday, February 10 of 2016, where patrons attend a church service, or mass, and receive black ashes in the shape of a cross on their forehead. The ashes symbolize the ultimate mortality of humans, but also act as a symbol proclaiming the wearer’s commitment to self-examination and repentance. The period ends on the Thursday before Easter, known as Holy Thursday.

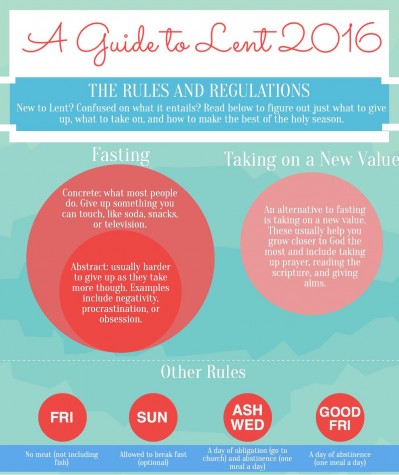

Fasting for Lent comes in different shapes and sizes. The church teaches Catholic children to give up a concrete object like soda or candy for the duration of Lent. As followers of Christ grow up, the concrete turns into abstract, like fasting from obsession, procrastination, or negativity. Still, other Catholics decide to take on a new value or practice instead, like prayer, service to others, or giving alms.

Furthermore, Lent requires no meat on Fridays, days of obligation (attending church services), days of abstinence (one meal per day), and repentance (going to confession). The exclusion of meat reflects the time of the Bible, when giving up meat meant giving up greed and expensive obsessions. Days of abstinence reflect the nature of the holiday, paired with attending church services and confession.

The experience of giving up sin or taking on a new value seeks to help Catholics grow closer to God and examine their own habits to prepare for the rising of Christ from the tomb.

All of the rules and regulations for Lent can seem overwhelming, but it comes down to fasting or taking on a new value, and then abstinence and penance.

“Lent is about conversion, turning our lives more completely over to Christ and his way of life,” Catholic website Catholic Online said. “That always involves giving up sin in some form. The goal is not just to abstain from sin for the duration of Lent but to root sin out of our lives forever. Conversion means leaving behind an old way of living and acting in order to embrace new life in Christ.”

Before Mamo started the experience, she did not understand Lent.

“I like traditions and stuff like that so I always thought Lent was interesting, but I wondered why people did it. I believe that God doesn’t really want you to punish yourself, so I didn’t understand the reasoning behind the suffering,” Mamo said.

I never thought about Lent like Mamo. Lent, to me, does not denote a cruel God who longs to see our suffering. Instead, Lent gives me a chance to put myself in the shoes of Jesus and to reform myself as both a Christian and a human.

The Ultimate Experiment

My Catholic upbringing allowed me to participate in Lent from an early age. As a child, I remember giving up soda for forty days and complaining as much as possible, looking forward to Easter so I could indulge again in the bubbly drinks. As I grew older, I started to look at Lent as an opportunity to better myself not only as a Catholic, but as a human.

I grew up with a lot of non-Catholic children; they would never understand when I told them I could not eat chocolate or meat. When I explained, they praised my courage and claimed they could never do it.

By the time February rolled around, I pondered how I wanted to celebrate Lent and how to improve myself for 2016. I realized, thinking about those kids, that the feat I accomplished every year could apply to more than just myself.

I asked a close friend of mine, junior Bethel Mamo, if she would want to try putting herself through Lent and she responded with unexpected enthusiasm. She immediately began planning what she would give up, and we both looked forward to seeing each other’s experiences play out.

We each decided to try out every aspect of Lent, which meant doing all of the options mentioned above. We each gave up a concrete sin, an abstract sin, and took on a new value. In addition, we fasted from meat on Fridays. To keep track of our Lenten experience, we journaled daily.

When Fridays call for no meat, fish becomes a popular meal choice. Catholic churches often hold fish fries on Fridays for all parishioners observing Lent.

For my sacrifice, I gave up snacks between meals, self-centeredness, and took on prayer and scripture. I fasted from snacks for Lent a couple of years before, and knew the waiting between each meal allows for true appreciation for the food and I could donate any money not spent on snacks to charity. I chose self-centeredness because I knew I struggled with it. Lastly, I took up praying twice a day, a habit I previously fell out of, and read from a devotional daily.

Mamo followed along the same lines, giving up unhealthy snacks, procrastination, and taking on reading scripture.

“I am always looking for different types of chips and every time we have them in the house I eat so much of it,” Mamo said. “Being addicted to anything is bad in Christianity, so this means I can’t eat chips or cookies even if they are part of a meal. As for procrastination, I always lie to myself and say I’ll do something but then never do it. It really wastes my time.”

We set out with the goal to journal everyday about our experiences and rated each day on a scale of its difficulty (0 as super easy, 10 as super hard), and our success (0 as not successful at all, 10 as the most successful).

Mamo and I quickly made our decisions on what we wanted to give up for Lent. We each chose a concrete sin, an abstract sin, and took on a new value.

Trial and Error

Starting on Ash Wednesday, Mamo and I found a passionate zeal for the upcoming Lenten season. With our goals in mind, we pictured the best possible scenarios.

“At first I was like I’m going to eat healthy from now on, and I am going to read the bible every night,” Mamo said. “And then week two I was like I’ll try doing all of that stuff but no promises, and then week three it was like, this is getting harder.”

In the first week of our journaling, Mamo and I recount the highs and lows of each day and list our successes and failures, no matter how small.

“When I went to see Deadpool, I got a coke and I was not tempted by the evils of popcorn. I hope it makes up for breaking the other day,” Mamo said on February 12.

My journal entries revolved around my devotional readings and their capacity to affect my life.

“Let me just explain here,” I wrote on February 22. “I was just in the process of trying to make myself feel better for my singing at rehearsal (which I am so self-conscious about) when I came across the headline [in the devotional]: ‘Don’t Be Afraid of Your Weakness.’ It’s like this is a little note from God saying, ‘Look, you’re not perfect. But do not fear failure.’ That is exactly what I needed to hear.”

On days when we would cheat, we looked back in regret and strove to do better tomorrow. We delivered on our promises for the most part, until the third week, where our habits parted ways.

By the time Mamo entered week three, she started to slip with remembering to journal and read scripture.

“When it was the third and fourth weeks, homework started piling up and then I had to journal and there were days when I would forget or would say I would do it when I finished my homework but then I would be so tired,” Mamo said. “I kept saying ‘tomorrow, tomorrow,’ but then I never did it.”

The repetition of the scripture also hindered Mamo’s ability to keep up with her fasting.

“I just forgot to read scripture because I don’t like reading on a schedule. Everything was about how God loves you and he sacrificed for you and I was like ‘Okay look by the third week I get it. I know,’” Mamo said.

My Lenten experience stuck to the books a lot more. I controlled my longings with more ease. Still, I did not complete the fast perfectly: I forgot to read a devotional or engaged in conceit with increasing frequency as Lent came to a close. The famed Catholic guilt reminded me of my failures, though, causing me to force myself to do better the next day.

I do not mention my success to put down Mamo’s experience, but as a contrast. Well-equipped with the Catholic ideal of suffering, I understood the difficulty when I started and accommodated the fasting to my life quickly and efficiently.

Looking at our ratings for difficulty and success, one can see a significant difference. Mamo’s success rate averaged out to a five on our makeshift scale, and her average difficulty rating almost hit six. Mine averaged out to seven and four, respectively. My previous experience with Lent helped me to take on its challenges without falling into too much temptation, and my guilt kept me going; Mamo’s lack of experience left her susceptible to breaking habits and the difficulty outweighed any guilt she felt.

Long-Lasting Effects

After 47 days of fasting and striving to improve ourselves, Lent ended on Holy Thursday, the 24 of March. Mamo and I looked back on the experience to discover what changed.

The tally count of days seemed daunting in the beginning. The daily reading and journaling grew annoying, and it took awhile to adjust to the hunger of forfeiting snacks. Eventually, though, it felt like just a drop in the bucket.

“It did feel like a long time, but now thinking back it doesn’t feel like that. When you’re in it it feels like the longest time but once you’re past it and you look back, it’s nothing,” Mamo said.

Even in the first week after Lent ended, Mamo saw the habits she formed during Lent carrying over into her own life.

“To be honest I did start eating healthier. I forgot to read bible verses, but I still believed in God. I haven’t procrastinated since Lent began and I am able to divide my time way more wisely than before,” Mamo said.

The same goes for my experience. Every time I complete Lent, the habits linger. I continue to pray, to search out the messages I read in the devotions, and to catch myself on conceit.

Lent functions psychologically by starting new habits that take hold and improve character.

My Lenten experience helped me to curtail my unhealthy habits and taught me to trust in my own abilities. The meal planning helped me to eat healthily large portions of food, which I do not always do because of lack of time. The devotional readings allowed me to learn more about Christian values and trust in my faith to help me through formidable situations.

For Mamo, the idea of control reigned supreme: “I learned I need to control myself. Going through this it became more obvious that it’s really hard to control yourself. I would recommend the experience for people to learn to control themselves, because it is really helpful I think,” Mamo said.

While Lent comes with the stigma that only Catholics, or only Christians, can or should attempt the fast, our Lent experience says otherwise. Lent may be rooted in one of the oldest religions, but it does not require faith in God to complete. Anyone can benefit by purging an unpleasant habit from their life or taking on a new trait to improve themselves. Society tends to relegate fasting to a religious rite that sounds too frightening to attempt, but trying to improve oneself as a member of that society should be, in line with the meaning of the word “catholic,” universal.