In a Barbie world: Women of color excluded from fashion industry

December 19, 2016

The beauty industry covers a broad spectrum of businesses. From nail polish to handbags, designers create products appealing to the public eye, specifically for women. Unfortunately, regardless of the product sold, these businesses share a common flaw: lack of diversity, especially when it comes to makeup and fashion. The choice to express oneself through fashion and makeup can provide confidence, but can society call it empowerment if only white women benefit from the choice?

Women face subtle discrimination in cosmetics. From light beige to dark tan, foundations offer an array of shades for lighter, or white women; meanwhile, companies limit women of color as a whole to about six shades.

Too Faced sells liquid and powder foundation, both of which received four star ratings by satisfied customers at Sephora. The shades allegedly range from medium to deep, but the liquid foundation offers four shades for black women, the darkest of which matches the tone of a brown skin woman. The powder foundation only goes as far as deep tan, not even bothering to make any shades for women darker than a paper bag.

Brands such as Bobbi Brown, Make Up Forever, and Anastasia Beverly Hills do well with providing an equal variety of shades for all skin tones. However, these high-end products come at a cost. Usually only sold at stores such as Sephora and Ulta, or online, they limit access to products that actually include darker women.

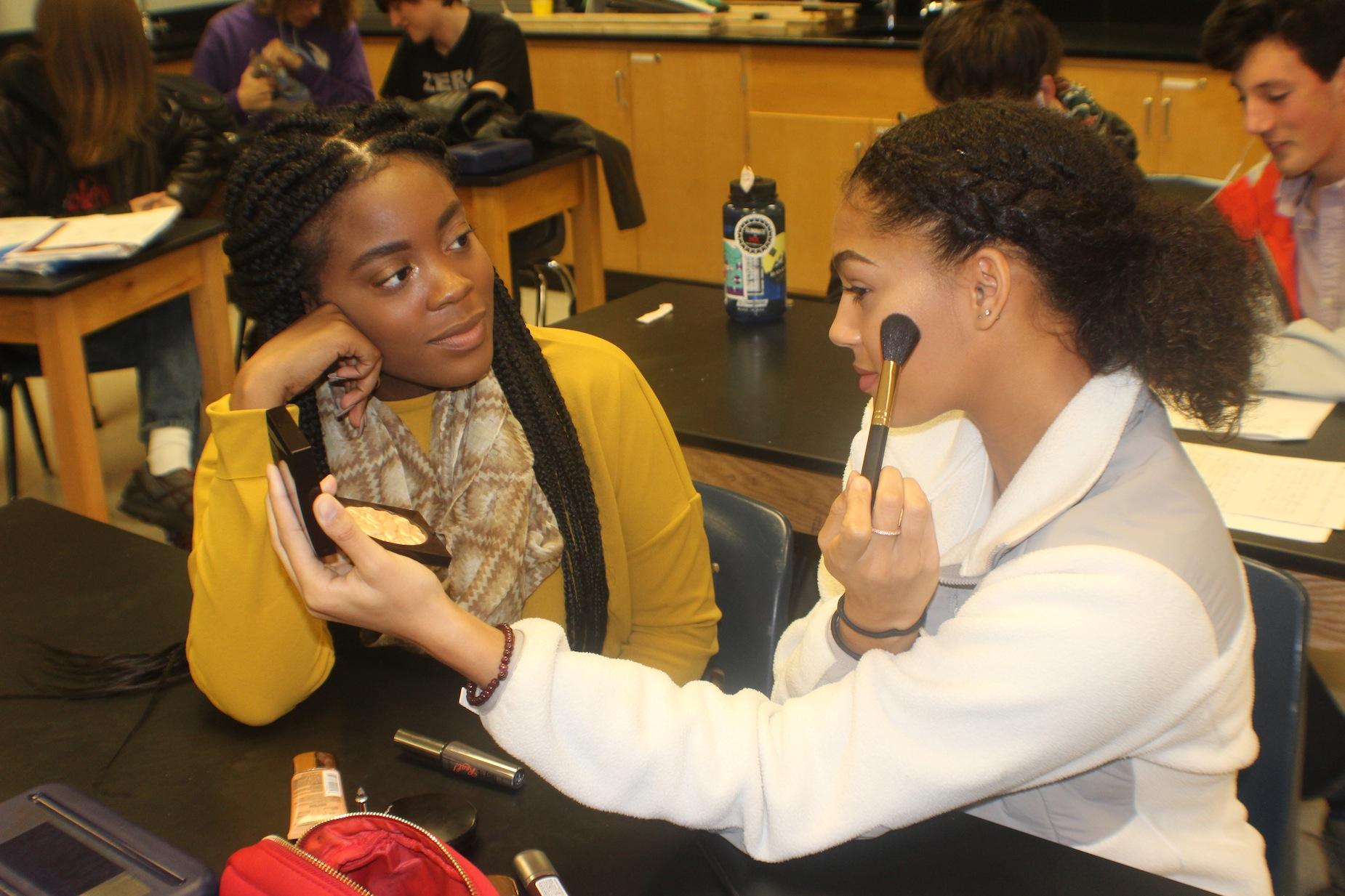

“I love L’oreal and Make Up For Ever, but I can’t afford Make Up For Ever a lot of the times. It’s great quality, but it’s expensive for a 17-year old,” senior Taylor Toney said.

It might sound like shallow cries for more makeup, but the problem runs much deeper than that. Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie rejected this notion, arguing, “Our definition of what normally comes across as powerful very much reflects male ideas, and the things our society traditionally considers masculine are not things that we generally think of as shallow or frivolous. There are many intelligent, thoughtful, innovative women who are interested in beauty and fashion, and we shouldn’t have any judgment about that.”

Discriminatory issues still matter, feminine or not. People do not notice exclusion until it consistently and specifically affects them. White women can visit any makeup store and find quality products in an assortment of shades, while a woman of color must jump through hoops to find four shades that might match her skin.

Marc Jacobs recently came under fire for the lack of diversity in their new line of foundation; at $55 a bottle, description boasts about the product’s oil-free formula and “24 hour full flawless coverage.” However, out of the 22 shades available, only three match the tones of darker women.

At the same time, Jacobs exploited black culture in his Spring-Summer 2017 show where he put faux dreadlocks on white models. He responded by calling “all who cry ‘cultural appropriation’ or whatever nonsense so narrow minded,” especially because they “don’t criticize women of color for straightening their hair.”

Picking out parts of a cultural identity to make a fashion statement only feeds into the paradox that women of color face in society; companies do not consider ethnic women when creating their products, but only how to use their culture to sell those products. Instead of hiring black models with dreadlocks, he justifies his appropriation by attacking black women for their own attempts at assimilation. Jacobs makes it clear that using black culture to sell his products comes before making a product for black customers.

This idea brings light to another aspect of the beauty industry that discriminates against women of color. When it comes to fashion, colored women experience exclusion from jobs in the modeling industry, as well as continued prejudice following employment.

Notoriously whitewashed for decades, fashion did not allow ethnic women to model. Besides pure racial bias, designers felt that only white women could present the “high-class” look they wanted. Naomi Sims and Iman, considered the first black supermodels, broke the glass ceiling for women of color in the 60s and 70s, but the industry remained far from diverse.

By the 90s, women like Tyra Banks and Naomi Campbell took to the runway, proving that black women could appeal to consumers. Alek Wek, credited with influencing people’s ideas on beauty, opened the door for dark skin girls without eurocentric features in the modeling world. Nowadays, every household knows Chanel Iman, Beverly Johnson, and Grace Jones. Does that mean models of color no longer struggle with inclusion?

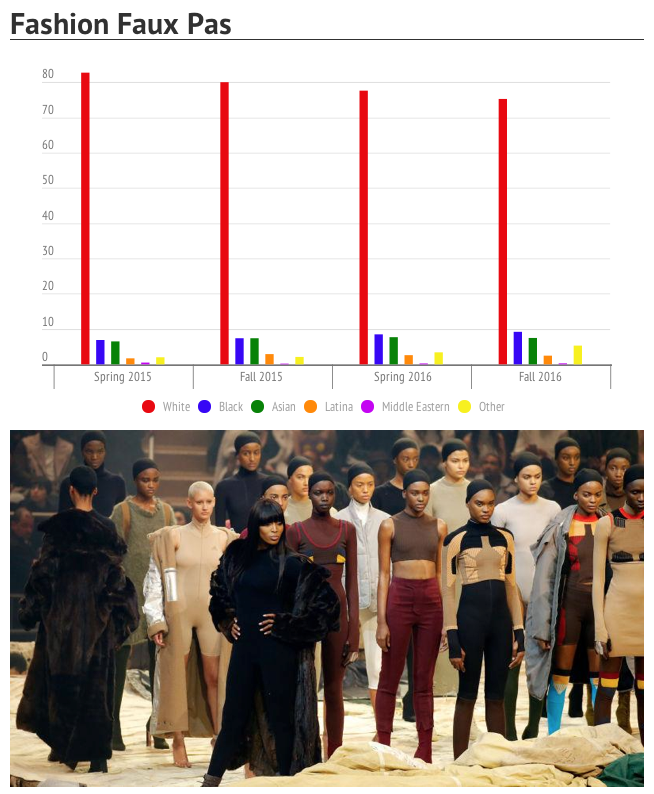

According to diversity reports released bi-annually by The Fashion Spot, during the Spring 2015 season, runways and castings sampled from Milan, London, New York, and Paris identified as 83 percent white on average, with less than a quarter of colored models at 17 percent.

In the next year, gains in diversity stayed low, but still showed achievement; runways and castings sampled from the same cities identified as 77.6 percent white, with an increase in ethnic models by 5.4 percent. Designers like Chromat, Tracy Reese, and Sophie Theallet led the way in diversity, putting on multicultural shows where women of color accounted for 60 to 70 percent of the cast.

Kanye West attempted to bring color to the fashion industry with his Yeezy Season 3 show, casting all ethnic models. Despite his feat, non-white models still have a long way to go. This graph shows the reports conducted by the online news conglomerate, The Fashion Spot, examining hundreds of shows and thousands of model castings from New York, Milan, London, and Paris. From Spring 2015 to Fall 2016, diversity increased by 7.45 percent overall; Black models jumped 2.32 percent, Asians increased .98 percent, Latinas on the runway increased .76 percent, and models in the other category are up 3.39 percent.

Despite the statistics, models still claim that the fashion industry shows nearly no signs of progress. Last year, Naomi Campbell sat down with SHOWstudio host Nick Knight and pointed out that although diversity continues to improve, racism still affects the women trying to reach the top in the industry.

“There is still an issue of ignorance in our fashion world,” Campbell said. “I don’t even like to use the word racism, I find it to be the word of you’re ignorant. They don’t want to change to be more open-minded and book a beautiful girl regardless of her creed and color.”

Additionally, she believes designers only use ethnic models to follow a trend; they will hire models of color for a period of time, but stop once the novelty wears off. Campbell does not see this as progress.

“We are not a trend, it shouldn’t have to be this way. I didn’t work 28 years for this to be a trend,” Campbell said.

Victoria’s Secret model Leomie Anderson also voiced her opinion on women of color in the modeling industry in an interview with MTV International.

“You feel very offended by it as a black person in general, but as a model you feel like, I’m sitting here next to a white model and I am the one being mistreated,” Anderson said. “As a black model you always feel like you have to bring extra stuff or be prepared that you are maybe going to be spoken to in a certain way at a casting or at a job. It’s just really unfair.”

These powerful quotes speak volumes to the concept of colorism, the practice of discrimination by which a person or institution treats those with lighter skin more favorably than those with darker skin. Alice Walker, author of The Color Purple, coined the term in 1982 in an essay collection titled In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. Colorism usually occurs inside one race; for example, Asian culture viewed fair-skinned women as royalty, while perceiving dark skin as a sign of peasantry. In this instance, colorism extends across cultural barriers and affects ethnic women trying to succeed in fashion. By creating the perception that light skin equals beautiful skin, companies push aside darker women with the beauty and potential to model for Balenciaga and grace the cover of Vogue.

NC senior Sinclair Gibson’s experiences as a model prove this statement true. Gibson took up modeling three years ago and instantly fell in love with it.

“I really enjoy it, it’s a way to express what I love to do. Plus, the free clothes aren’t so bad either,” Gibson said.

However, Gibson experiences the same struggles that these supermodels describe.

“Sometimes you go in knowing that the cards are stacked against you, especially when you know the designer is known for having a certain look,” Gibson said. “I’ll go to a go see or a casting call and notice I’m the only black model there; they’ll even let you get to the final cuts and make you feel like you actually have a chance.”

Regardless of age, location, and notoriety, most models of color share the same feeling of rejection from the industry purely because of their skin tone. The same goes for makeup artists and enthusiasts that want to express themselves in a community that offers them little support. A harsh truth to accept, but the truth nevertheless. As a nation, as women of color, the first step to breaking the glass ceiling lies in creating discussion and bringing attention to topics that affect everyone.

“We have a problem with representing every color, and it can’t be fixed until we address it,” Gibson said.