Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

How America constantly prosecutes rap

December 8, 2022

In the early 1970s, the rap genre flourished in New York City as DJs fused elements of funk, soul and disco songs into one conglomerate of music. While they played their unique sounds at block parties, people would soon talk and rhyme over the music in sync, thus curating the unique genre of rhythm and poetry. As time progressed, so did the sound of hip-hop. Due to it originating from a community of people of color (POC), several artists used this genre to bring awareness about social injustice toward African-Americans. Several artists in the 1990s tackled issues such as police brutality and gang violence that would make for powerful anthems for future generations, with infamous songs like N.W.A’s “F*** Da Police” still talked about in discussions of racial profiling. In nearly 50 years, Hip-hop continued to evolve into various subgenres where artists could either focalize on introspection and lyricism or curate music solely based on catchiness and replayability.

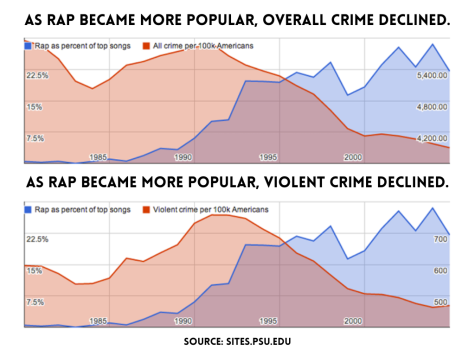

Despite its origins, political statements and current popularity, various people in the United States view the entirety of rap as violent. In 2008, Pew Research Center discovered that roughly 70% of the American public believed that hip-hop negatively impacts society. While popular rap songs such as “Crunk Ain’t Dead” and “Stop Breathing” certainly promote violent behavior, context matters for black rappers. Artists such as 21 Savage may glamorize violence in his music, but for him, it acts as a way to garner revenue as people want him to rap about murder and pistols. Several black artists also come from poor neighborhoods with low incomes, so rappers will lie about their actions because humans naturally crave violent behavior within media, hoping for a chance at admiration in the mainstream realm.

“I don’t think hip-hop instigates violence unless it’s what the artist is trying to make it about. I feel like teenagers get different ideas about what the artist is trying to talk about, but it really depends on the artist and their background. Other than that, it’s just music that has feelings and emotions just like other genres,” senior Abigail Trout said.

Ben Shapiro, a controversial figurehead in conservative media, strongly believes that rap does not meet the qualifications of music. Regardless, the genre resonates with numerous generations and continues to act as a vessel for black people to voice injustices. In 2015, Kendrick Lamar famously performed his hit song “Alright” at the BET Awards, where he performed the Black Lives Matter anthem on top of a cop car with an American flag waving in the background. Due to pre-existing biases of hip-hop in conservative media, Fox News found the performance distasteful and derogatory.

The belief that hip-hop perpetuates violence lingers in the American judicial system. In 2015, Tennessee convicted aspiring rapper Christopher Bassett for the murder of Zaevion Dobson. At the trial, prosecutors showed the jury one of Bassett’s music videos as evidence against him, which certainly perplexed hip-hop fans. The music video did not hold any relevance to the case whatsoever, as it did not mention the victim and Bassett recorded the video months before the murder happened. Prosecutors would continue to argue that Bassett’s violent language in the video implied confession to his first-degree murder charge.

Another example of rap lyrics used in trials includes Vonte Skinner and his involvement in a 2005 shooting. In his trial in 2008, the prosecutor extensively used Skinner’s rap lyrics against him, and read the jury 13 pages of violent lyrics written by the defendant. Once again, these lyrics held no relevance to the shooting and no mention of the victim. Yet, the prosecutor persisted in showing the jury this evidence, as the other evidence relied on witnesses against Skinner who changed their stories multiple times. These lyrics left such an impact on the jury that they found the defendant guilty of attempted murder, sentencing him to 30 years in prison.

In 2013, the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey found that in 18 cases in which courts across America could have considered the admissibility of rap lyrics as evidence, they allowed it roughly 80% of the time. Although it may sound minuscule, prosecutors increasingly presented rap lyrics to juries over time. In 2020, liberal arts professor Erik Nielson claims that he saw over 500 instances in which they used this strategy.

“As an expert witness, my job is to correct the prosecutors’ characterizations of rap music. They routinely ignore the fact that rap is a form of artistic expression— with stage names, an emphasis on figurative language and hyperbolic rhetoric— and instead present rap as autobiographical,” Nielson said.

Prosecutors intentionally present rap lyrics as character assassination against the defendant. Despite rappers utilizing their songs as a form of artistic expression, prosecutors will nitpick certain lyrics in rappers’ discographies and assert that their words remain truthful. It does not matter if the defendant did or did not do the crime, but rather how the jury became impacted by the presentation of violent and graphic lyrics. As previously mentioned, Skinner’s jury initially sentenced him to 30 years in prison, and after the questionable presentation of a music video in Bassett’s trial, the jury sentenced him to life plus 35 years. The antagonization of rap in court cases preserves existing juror bias, and defendants receive a slightly unfair trial.

Despite the frequent use of rap lyrics in judicial settings, the Supreme Court already ruled the use of protected speech as evidence unconstitutional in 1992. In the case of Dawson v. Delaware, the state attempted to introduce the defendant’s Aryan Brotherhood tattoo as evidence. However, the court denied the usage as both the defendant and the victim identified as white, therefore the court deemed the evidence as irrelevant.

Thirty years later, this sentiment of “protected speech” somehow applies to white supremacist prison gangs but does not apply to hypothetical lyrics from rappers. In addition to the prosecution of rappers, no other music genre faces such consequences. For example, Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody” remains a classic renowned by As a soft piano plays in the background of the song, lead vocalist Freddie Mercury infamously says “Mama, just killed a man/Put a gun against his head, pulled my trigger, now he’s dead”. Even with the inclusion of this bizarre lyric, fans still view it as the greatest song of all time. While pop music contains a similar amount of aggression compared to hip-hop, media outlets misinterpret the words of prominent rappers such as Kendrick Lamar. In a similar fashion, prosecutors do the same when they showcase rap lyrics as autobiographical.

The concern of using rap lyrics as evidence rises once again, as members of Young Stoner Life Records (YSL) face severe RICO charges. Prosecutors curated an 88-page indictment for the upcoming trial, where they pinpoint Young Thug as the leader of a criminal street gang. However, a portion of the indictment reveals a constant issue for rappers on trial, as prosecutors cited specific lyrics and social media posts that allegedly prove criminal intent. Gunna, a YSL artist charged with a singular count of racketeering, remains in prison after a Fulton County judge rejected his bond for the third time. Prosecutors referred to his music and claimed that specific lyrics contributed to the RICO conspiracy, but Gunna’s lawyers stated that he based his lyrical content on entertainment purposes and that his music “provides no basis for denying bond”. In fact, his law team stated that the RICO indictment only charged the artist with violating the Georgia window tint statute. As of now, both Gunna and Young Thug remain in their prison cells, and the YSL trial will officially begin next year in January.

“Before, I felt upset about the YSL case because I felt upset concerning rap lyrics and creative freedom. But then again, rappers should be more careful on what they say because he kind of set himself up,” junior Ralph Philogene said.

The indictment of YSL angered several fans of the “pushin P” artists, as they started the year as superstars with a song that earned a spot on the Billboard Hot 100. Now, prosecutors and judges alike have kept them inside the same Fulton County jail. As supporters hold up signs that state “FREE YSL” and “Protect Black Art” over their heads at music festivals, rappers like Fat Joe portrayed his frustrations on national television by performing a Young Thug song at the BET Hip Hop Awards. Hip-hop fans across the nation showed their contention with lyrics presented as evidence, and their protests recently impacted American politics. As of September 30, 2022, California lawmakers signed the Decriminalizing Artistic Expression Act, which states that prosecutors may only use lyrics if they depict factual and relevant details. When California governor Gavin Newson signed the new law at a virtual meeting, influential rappers such as Meek Mill and Killer Mike attended the meeting to show support. Reform also appears now on a nationwide scale, as bills such as the Restoring Artistic Expression Act become introduced to Congress. Regardless of an individual’s perspective on hip-hop, the ethics of prosecutors using an artist’s own art against them remains questionable.