Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

The art of language

December 19, 2016

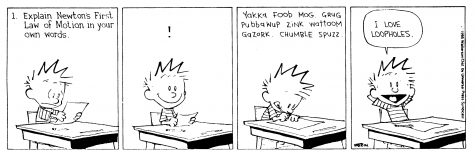

At one point in many people’s childhoods, they dream of creating their own secret language. They imagine developing a nonsense alphabet, and using it with their friends to communicate behind their parents’ backs. For most, this progresses no further than a brief flirtation with Pig Latin, but for a few, these dreams never went away. In adulthood, they put nonsense words into vocabulary tables and organize them with fully-structured grammar, bringing them all together to create conlangs (short for “constructed language”).

Most monolinguals would think one can create a language with a minimum amount of effort: just switch out English words for made-up ones. However, they ignore the grueling truth of language, a truth that any language student could testify to: speakers cannot learn most languages with ease. Conlangers mould aspects of language most speakers would never think to question into interesting, bizarre, and sometimes even unnatural forms. For example, the practice of treating the “he” in “he hugs John” and “he eats” the same, or ordering a sentence by placing the subject first, then the verb, then the object.

So why would someone choose to undergo the brutal process of creating a language? Why choose to spend hours mapping sound tables, charting out grammatical systems, and adding one new piece of vocabulary at a time?

Contrary to popular expectation, most conlangers do not teach linguistics, or even study it in university; they usually come from much less professional origins, with reasons for developing languages that vary as widely as their languages themselves.

Pierre Suisand • Feb 11, 2017 at 6:30 PM

This piece was truly captivating and was extremely interesting to read. The Author is clearly a good journalist and reporter.

Juana Elena • Dec 19, 2016 at 7:53 PM

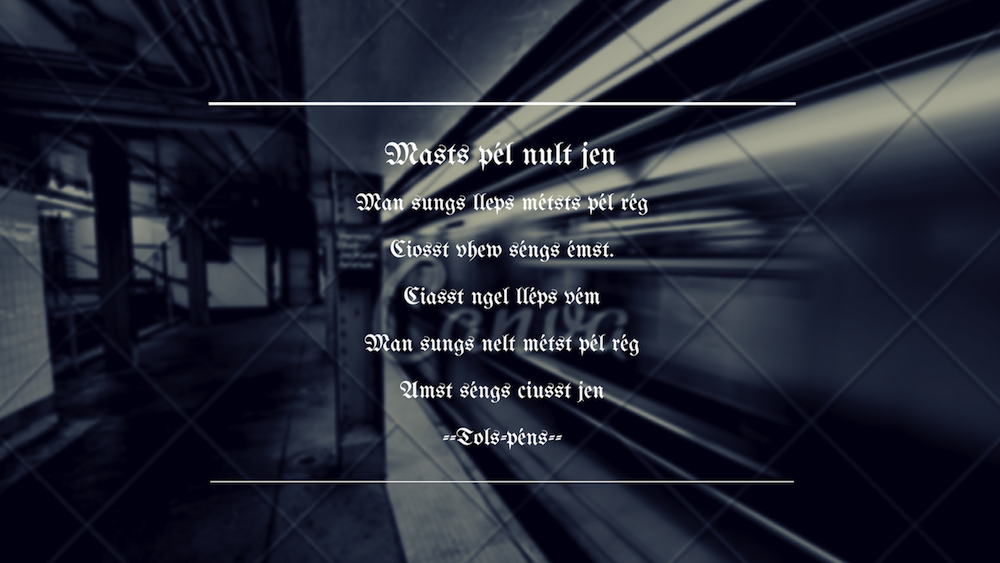

I found this article incredibly enlightening! Prior to reading it I had no idea of the history, depth and philosophy behind Conlang and the desire of the historical and current community to use it to build bridges among people. I also enjoyed the explanatory graphics, especially the Ithkuil example. Well done!