Your donation will support the student journalists of North Cobb High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

The impact of thrifting’s rise to popularity

April 14, 2021

In recent years, the cloud of stigma surrounding thrifting has dissipated. Certain demographics previously looked down on the idea of wearing someone else’s old clothes, but that mindset has begun to shift.

Those who shop second hand can trace a portion of thrifting’s destigmatization to the 2008 recession. This unexpected period of financial hardships increasingly led people to reclassify purchasing an article of clothing for a discounted price as an accomplishment instead of a source of shame, mirrored by the COVID-19 pandemic that continues to cause the same result.

Preceding those events, thrifting’s popularity also spiked during counterculture movements that emphasized the importance of avoiding materialism. In the 70s, shopping at thrift stores became normalized for those who participated in the hippie counterculture and rejected the time’s consumerist goals.

In the 80s and 90s, the success of artists such as Kurt Cobain of Nirvana and Eddie Vedder of Pearl Jam popularized the grunge subculture growing out of Seattle, Washington. Purchasing clothes secondhand fit the subculture’s standards of deviating from societal standards of materialism, and thrift stores gained another connotation from association with this group.

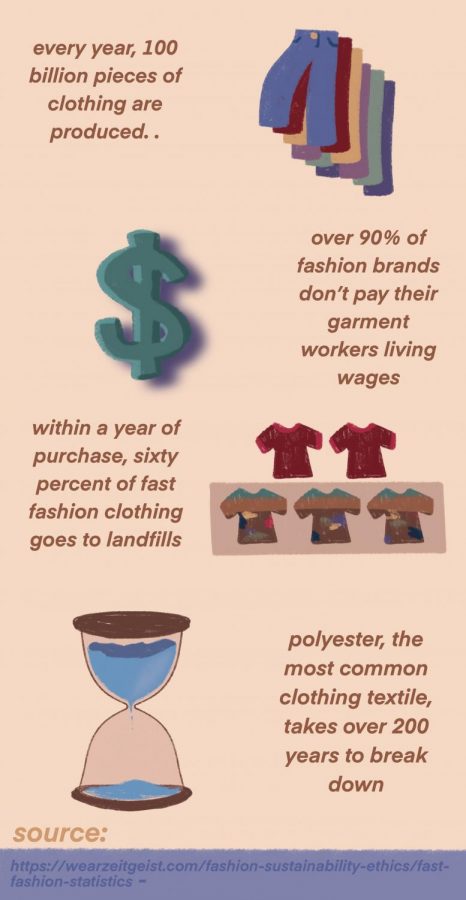

In the rising generation, concern for the effects of fast fashion and materialism on the earth increases, feeding partially into this cultural shift towards secondhand shopping. Fast fashion’s business model operates on offering consumers the most current and trendy clothing. When brands constantly aim to create and sell clothes in the newest fashion, concerns about the quality of the garment and the working condition of the employees frequently fall by the wayside. Information about the exploitation of workers who manufacture fast fashion feeds into its poor reputation, with environmental concerns continuing to grow as well.

Pollution continues to emerge from waste produced in textile factories, emissions released while shipping clothes overseas, and the clothes that pile up in landfills, frequently after less than a dozen wears. Beyond this, the clothing industry demands excessive resources, with the cotton grown for one pair of jeans requiring nearly eighteen thousand gallons of water. This statistic does not include the amount of energy needed to actually sew the jeans and ship them off to retailers.

With these concerns in mind, consumers search for new ways to purchase clothing without supporting this harmful industry. Environmentally sustainable brands such as Reformation have sprung up to supply customers worried about sweatshops and global warming with clothing, but these companies’ products come with a much higher cost. Stemming from the companies’ vows to pay workers living wages and source, manufacture, and handle materials safely, purchasing an entire wardrobe from ethical brands remains outside the reach of the majority.

Frequently promoted by youtubers and influencers such as Emma Chamberlain and Bestdressed, thrifting offers a remedy for those who wish to avoid fast fashion, but do not want to pay the price these higher profile brands require. With this perspective, the collective mind of the younger generation has changed thrifting from something shameful to a good deed.

“I started off thrifting when I was younger because my family isn’t exactly wealthy. And clothes cost a lot of money sometimes. So it was just easier to find stuff for cheaper. As I’ve grown older and have my own money, it’s still always better to go cheaper but now I do it more for the thrill and to be environmentally conscious. The clothing industry is so wasteful and hurts the earth immensely. So, I try to thrift what I can to help not support that so much,” junior Lauren Sloan said.

As physical stores began to benefit from this shift in thinking, online approaches to reselling pre-worn or thrifted items sprung up. Companies such as thredUP, Poshmark, Depop, and Swap quickly grew, with the online secondhand clothing market predicted to expand to a worth of thirty six billion dollars by 2024.

When COVID-19 began, these businesses gained an unexpected edge, as physical locations for thrifting and consignment closed and consumers turned to online shopping more than ever. Notably, thredUP continued to grow at a rate of 20 percent as lockdown orders became law.

However, as both in-person and online thrifting continues to grow, concerns have arisen from those scrutinizing the impact of thrifting’s trendy status on the populations who depend on thrift stores to clothe themselves. While likely unintended, thrifting excessively can negatively affect others by decreasing the amount of clothing available, especially when thrifting to resell. This, in turn, may force thrift store prices to rise over time to meet the demand with a limited inventory. These actions hold the potential to cause damage, especially when practiced in a low-income area where the majority of shoppers thrift from necessity, not choice.

“I think it’s a great way to shop more sustainably. I don’t think thrifting becoming more normal and popular is bad per se, but I definitely have issues with mass buying to resell and the like. Especially when people go into lower income areas, a lot of those clothes will be the best options for those in the area so buying up anything nice can cause a lot of problems. As well, prices jump when stores know they can get more profit, so giant resale hauls can contribute to prices inflating,” junior Amelia Oni said.

A similar moral conundrum has arisen around thrift flipping, a practice where creatives with a sewing machine purchase second hand clothing and alter it to create a new piece. This process frequently requires skill and creativity, as those who thrift flip face a new set of challenges with each garment. While an inventive way to reuse clothes and express one’s sense of style, it sparks controversy, as those who thrift flip frequently purchase plus size clothing to flip. Suffering economic disadvantages increases one’s chances of being obese, so the practice of thrift flipping may unintentionally take clothes that a different demographic actually needs.

“Thrifting’s popularity has definitely worked good and bad in ways. It’s much harder to find things for sure. The main problem I’d say is people buying bigger things to alter them. Plus sizes are really hard to find in thrift stores and not everyone can fit the smaller sizes,” Sloan said.

Now, shoppers from nearly every demographic visit thrift stores, drawn by the desire to emanate past and present styles with the added benefit of low prices and unique pieces. Discussions surrounding the ethics of thrifting continue to swirl, but the practice’s newfound popularity shows no sign of declining.

“I love thrifting because you find pieces that no one else has. Thrifting also can provide you with the wardrobe you want for half the price. It’s a treasure hunt every time you go and it’s such a fun experience… I think that with this new popularity it helps the planet, it provides people with more fair options, and it creates a fair playing ground for fashion. On the other hand though, it is harder to find more popular items like mom jeans or cardigans, but overall I think it’s a good thing it’s more popular,” Riverton High School junior Shannyn Krietzer said.