The term aesthetic originated with the Greek word aisthētikós, which represents a relation to sensory perception. The word’s association with beauty began when German speakers adopted the term in the 18th century. Since the word’s emergence in the English language, its use has expanded to describe an object’s visual essence. The modern it-girl summarizes her environment, her likes and her dislikes through various looks. Whether she prefers clean girl or coquette, this internet user’s preferences fall into a niche, easily discarded aesthetic. As this person aims to achieve the coveted vibe, he or she purchases items that appeal to a particular taste, items that the buyer may no longer want in the time that follows.

“It [the impact of your aesthetic] really depends on what values you want to have. Do you want to value an aesthetic for a few months and then switch it, leading to more excessive overconsumption or do you want to stick with one value or aesthetic? One way will lead to more items in landfills and one way will ensure that the majority of items bought are used to their full potential,” Eco Warriors secretary and magnet junior Simran Kant said.

Alongside the word aesthetic, the Industrial Revolution also commenced in the 18th century. Increased use of fossil fuels, access to inexpensive products and abandonment of provincial lifestyles each grew during this time. These changes arose due to developments in factory manufacturing, so people could use machines to cheaply and efficiently complete work previously done by artisans. These machines operated through coal combustion, which released smoggy air, called greenhouse gasses. Although these gasses, such as carbon dioxide, belong in Earth’s atmosphere, the increased presence caused by unbalanced anthropogenic activity contributes to global warming.

Similarly, as affordable access to materials expanded, people in economic groups that previously might have acted frugally gained access to disposable income and cheap products, creating a sense of disposability in their possessions as well. This growth in access assisted the economy and quality of life but took a toll on the environment. Trees turned black, the air grew smoggy, and murk flourished in the water. Capitalists brought this about for the production of beautiful objects to fill equally produced beautiful spaces.

Since the development of industrial production, efficiency has only increased. This productivity, again helping economic development, harms the environment because it allows people to overconsume. As developed societies normalize this once-marvelous expenditure, it grows, only furthering the environmental effects. Now, clothing companies manufacture a surplus supply of clothes that purchasers do not buy, inducing the industry’s annual failure to sell between 10-40% of produced clothing. Farms grow crops sold in grocery stores that purchasers never use, leading to the 60 million tons of food waste ending up in America’s trash cans, but the importance of TikTok’s latest kitchen gadget trend easily overpowers overproduction’s issues’ value. Teenagers’ perceptions of these trends’ importance contribute to product creation, overproduction and resource use, but as manufacturers ship out new items, the old ones continue to take up space in landfills, piling up with the fast-paced overturn of necessities. An important note, however, remains for consumers to consider; when one belongs to a particular niche, even certain trendy items that suit that interest can maintain environmental responsibility. The purchaser must utilize the item until it breaks and opt for quality, low-emission materials.

“We as a society need to overcome the economic approach of designing products for the dump. Although Perceived and Planned Obsolescence now dominate our economy and make profits for corporations, they cause our products to need replacement sooner, causing frustration in consumers and destruction to our natural world because of continuous additional raw material extraction. We have to come up with cultural strategies to overcome unnecessary consumption — by purchasing high-quality products that follow cradle-to-cradle design,” Berry College’s Associate Professor of Environmental Studies & Anthropology Dr. Brian Campbell said.

While human consumption in the first world mushrooms, the space people take up follows. These areas require wood, stone and metal to build, so habitat disruptions including deforestation and mining continue even in areas left undeveloped or unpopulated. While industry leaders have slowed deforestation since the 1980s, the mining industry has still felled almost 1.4 million hectares of trees in under 20 years, and other destructive environmental patterns remain. These materials’ necessity could drop with a declining creation of sizable homes and extensive gardens, work-from-home business culture and lessening motivation to follow architectural trends, each of which would decrease energy and lumber use.

Countries develop land to farm, industrialize and house their citizens and provide enrichment to members of urban communities. These spaces create beautiful fields of agricultural land, places to build goods that spark joy and complex buildings that generations may marvel at. Unfortunately, developed land, no matter its visual appeal, creates environmental issues that may fail to outweigh the benefits. While paved land increases, water loses its ability to seep into the ground, which can create a medley of catastrophic effects on the Earth and its populace. Similarly, as forests lose density for the sake of picture-perfect vegetables and frolic-worthy farms, soil erodes, carrying pesticides and fertilizers that harm the ecosystems that interact with them.

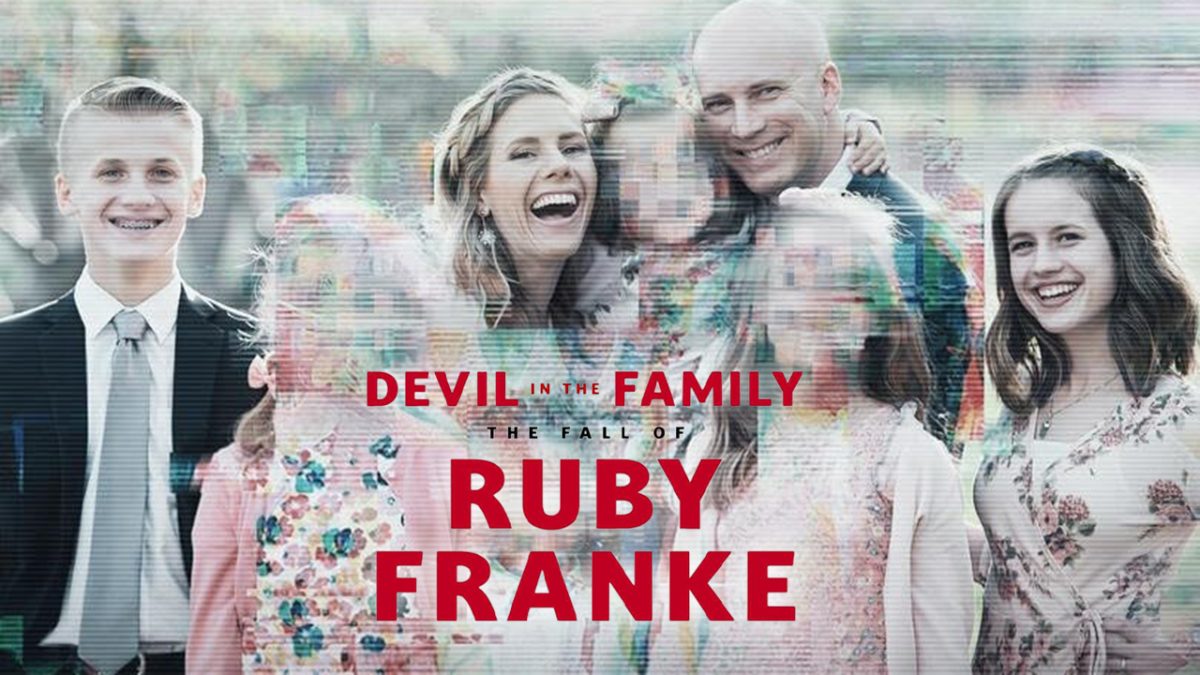

In the modern era, the First World community members consume a higher degree of materials than they could ever need. Americans’ exemplification of overconsumption — the unrestrained use of purchasable items that negatively affect environments and people — alarms environmentalists. Not all Americans possess the means to participate in a high rate of consumption, but social media and a need to appear wealthy have built a culture that normalizes and enables buying and selling beyond necessity. While the average citizen cannot purchase extreme Shein hauls or expensive appliances, they still may find it easiest to shop in places that sacrifice sustainability for profit. For example, the clothing brand Patagonia produces high-quality pieces with environmentally responsible materials, but the price of one sweater typically exceeds $100, with even the brand’s adult-sized beanies costing roughly $50. In comparison, the synthetic sweaters sold by fast fashion brands such as Shein tend to cost under $20. Concerning American wallets, investing in cheaper, lower-quality products can improve self-esteem as people attempt to follow the ever-changing trend cycle, but the massive manufacture of wasted textiles and quickly discarded clothes continues to create unnecessary pollutants as fabric production causes 20% of the Earth’s clean water pollution among its other drawbacks.

“[There is] a landfill in Chile in the Atacama Desert that is huge and it is primarily or exclusively filled with discarded clothing. Some of it still has tags on it, so there’s a bunch of Shein clothing just in this landfill in the desert. That’s just one indicator of environmentally unhealthy levels of consumption amongst men, and then there’s the fast fashion of a new style every six weeks. I don’t even know how to approach the fast fashion thing because it is just so big,” Vanderbilt University’s Director of Undergraduate Studies in Climate and Environmental Studies Dr. Zdravka Tzankova said.

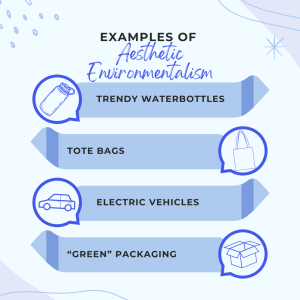

In contrast, certain purchase-based crazes encourage underconsumption core. This aesthetic, a recent trend on TikTok, emphasizes owning only one item or mending it before one throws it away. Though helpful in theory, these trends can contribute to overconsumption and its sister problems. Stanley, a reusable water bottle company, sold buyers on reusability and sustainability: low-plastic, low-emission water. Ideally, this aestheticization of sustainability can promote healthy lifestyles, but in reality, it creates a reverse effect. In 2019, Hydroflasks rose in popularity — and Stanleys followed. Recently, Owala water bottles took the internet by storm. While no one company may legally monopolize reusable vessels, the competing containers’ ability to come in and out of vogue drives home the idea that even sustainable consumption flails in the hands of popular culture or visual appeal.

Reusable tote bags also present visually appealing opportunities for self-expression, but studies, particularly one conducted by Great Britain’s Environment Agency show that these bags, despite their environmental marketing, rarely supersede plastic bags’ sustainability on a carbon emissions front. While one may hope the bags would pollute the planet less, people continue to purchase or receive these totes, creating luggage for their carbon footprint. Even the supposed sustainable choice falls to fads, with trend-chasers receiving word that a mini tote carried by Trader Joe’s now warrants purchase. The problem only becomes exacerbated as users continue to use plastic bags, therefore negating the hope that their reusable alternatives might eventually improve the user’s carbon footprint.

“I’m very concerned about toxins in various types of consumer products, and so my primary concerns are that we’re destroying the environment because we’re consuming so many of these things that we use for a little bit and then they end up in a landfill somewhere. My other concern is that a lot of cosmetics are not very well regulated for environmental and human health and safety. So two things I’m sad about when I see young people include [their] feeling like they need all these products and they want to try out and experiment with these facial care routines. It’s a massive generator of pollution both in manufacturing and disposal,” Tzankova said.

Perhaps a notably current issue, skin care fads exemplify people’s fascination with beauty’s negative environmental impacts, particularly for social media approval. While women and girls apply moisturizers and use serums and lather cleansers, water use, ocean pollution and landfill leaching increase. Among these skin care obsessions, the frequent reapplication of sunscreen takes precedence, but this ultraviolet light protection can enter waterways, carrying tetrahydroxybenzophenone. The chemicals can contaminate human drinking water and create toxic environments for the organisms that share the water, acting as endocrine disrupters and harming coral reefs. This sunscreen exists as a miniscule part of the cosmetic industry’s negative impact, with animal testing, the release of microplastics and the use of animals to create perhaps toxic fragrances, each contributing to cosmetics’ environmental destruction.

Humans contribute to Earth’s biosphere; they influence it, and it influences them. Regardless of whether their quest works toward beauty or safety, a negative impact follows. As people watch on, the guilt of existence may weigh on their minds, but effective change rationally can only come to pass through government and corporate regulations. By creating rules on the materials companies can use, limiting the quantity of their stock and regulating land use, these bodies can prevent the encroaching threat of beauty. As individuals, people can opt for mindful consumption, attempt to restore any land they control to its natural state and possibly review their understanding of glamor.

“I do buy things to make myself feel beautiful, like skincare or nail polish, but only if I need to restock usually. That’s really motivated by me not wanting to waste money but it helps the environment too. I wear a lot of accessories but I’ll get those second-hand. Landscape-wise, seeing something really beautiful and majestic puts me in this eco-warrior mindset, like I need to go green and never buy anything again and live off the land. But I know that’s not entirely feasible for me right now so I just save electricity and follow the three Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle),” magnet junior Allore Walters said.