Forgotten figures in Black History

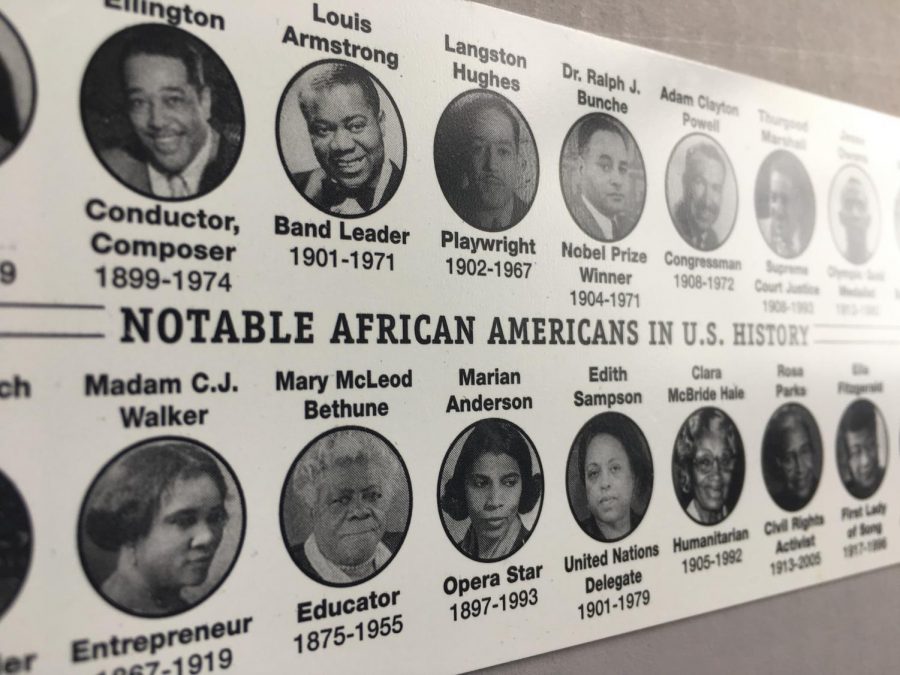

Every February, students remember notable African Americans for their suppressed accomplishments and efforts in the fight for racial equality. Although learning about these people nourishes the minds of young students, historians and educators alike deprive a multitude of African American figures of the credit they deserve.

February 27, 2018

Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Booker T. Washington— just three of the various names a keen student might hear during Black History Month this February. These influential figures shaped history and often receive praise for their courage and the sacrifices they made to aid African Americans in gaining equal rights. Their legacies will live on through the countless movies and monuments made in their honor. Regardless, the fight for equality involved more people than textbooks claim.

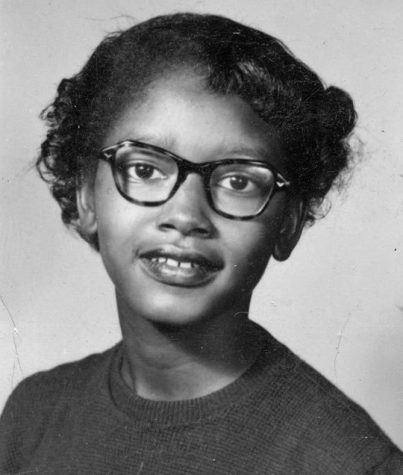

Claudette Colvin

The original Rosa Parks, Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat to a white passenger in 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama at just 15 years old. On her way home from school, the bus driver asked Colvin and her friends to move to the back of the bus so a white woman could sit in their seats. Her friends complied quickly, but Colvin remained, saying: “It’s my constitutional right to sit here as much as that lady. I paid my fare, it’s my constitutional right.” The bus driver told her that if she refused to move, he would call the police. Despite this, Colvin stood her ground. When the police arrived, they forcibly removed her from the bus and arrested her for assault, disturbing the peace, and violating segregation laws. She spent several hours in jail until her pastor bailed her out. That night, her family stayed awake in fear of retaliation.

“I was really afraid, because you just didn’t know what white people might do at that time,” Colvin said.

No one could ignore the fact that Colvin’s actions sparked a movement, especially the local chapter of The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). They knew that it could present a huge opportunity for the black community, but they did not want Colvin, a “mouthy” and dark-skinned young teen, to represent the movement. Instead, they suggested that Rosa Parks, a secretary for the NAACP at the time, lead the movement by refusing to give up her seat on the bus, thus writing Colvin out of history. Today, Colvin, now 78, lives a quiet life in New York as a retired nurse’s aide.

“Young people think Rosa Parks just sat down on a bus and ended segregation, but that wasn’t the case at all,” Colvin said.

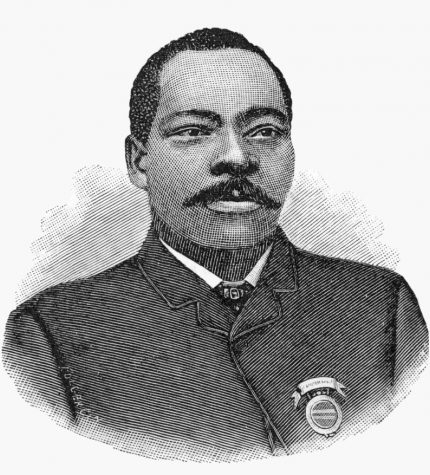

Granville T. Woods

Dubbed as the “Black Edison,” African American inventor Granville T. Woods held over fifty patents during his lifetime. Woods grew up in Columbus, Ohio in the late 1850s. He attended elementary school up until the age of ten and became self-taught in the mechanics field in order to begin working as an engineer. As a teen, Woods worked as an apprentice in a railroad machine shop and at a steel mill. Electricity and machinery fascinated him, so at age twenty, while living in New York City, he took courses to better his understanding of the subjects. After two years of studying, he found work on a British steamer, and he traveled the world before settling down in Ohio, where he formed the Woods Electric Company in 1880. In 1887, he patented the first of numerous inventions: The Synchronous Multiplex Railway telegraph, which allowed moving trains to communicate with train stations. This invention spurred countless more, including a system for overhead electric conducting in 1901, an improved steam boiler furnace in 1889, and an improved air brake system in 1904. Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the first functional telephone, purchased the rights to Woods’ “telegraphony,” a combination of a telephone and a telegraph, which enabled him to pursue a career as an inventor full time.

At the peak of Woods’ success, Thomas Edison sued him on the grounds that he invented the induction telegraph before Woods. Woods eventually won the lawsuit, but Edison, unsatisfied with his loss, invited him to work at the Edison Electric Light Company. Woods declined, preferring to work independently. By the time he died in 1910, Woods’ inventions prevented countless accidents and helped railways all across the U.S. function more safely.

James Armistead Lafayette

Born into slavery in New Kent, Virginia around December 10, 1748, James Armistead served his country in the war for independence by becoming a double agent and the first African American spy. In 1781, his master, William Armistead, agreed to let him join the Revolutionary War army at his own request. He served under the Marquis de Lafayette, the commander of French forces who allied with the American Continental Army. Lafayette employed him as a spy and told him to conduct espionage on the British camps. Armistead quickly gained the trust of the British officials, posing as a runaway slave. In fact, they trusted him so much that they employed him to spy on the Continental Army for them. Soon, Armistead moved freely between the opposing sides, delivering false information to the British, and helpful information to the Patriots, all without detection.

His most important contribution to the war effort came when the details from his reports allowed General George Washington to prevent the British from attacking Yorktown, Virginia. The Continental Army surprised the British by blockading the area and weakening their military. As a result, the British surrendered in Yorktown on October 19, 1781. Despite his heroic and loyal actions during the war, Armistead returned home and continued his life as a slave. Marquis de Lafayette wrote him a recommendation letter that enabled his freedom. To show gratitude for Lafayette’s kindness, he took his surname. After his emancipation, Armistead bought 40 acres of land and lived as a farmer until his death in 1830.

Fannie Lou Hamer

The youngest of twenty children, Fannie Lou Hamer worked as a sharecropper with her family in Montgomery County, Mississippi throughout her childhood. She excelled in reading and spelling at the one room school provided for the sharecropper’s children between picking seasons. Unfortunately, she left school at the age of twelve to take care of her aging parents. Despite this, her reading skills continued to improve, and in 1944, the plantation owner discovered she could read and promoted her to the plantation’s time and record keeper. She went on to marry Perry Hamer, a fellow sharecropper, and adopt two children. After receiving surgery for removal of a brain tumor, doctors also performed a hysterectomy on her without her consent, causing her to become unable to raise children of her own. All the while, her interest in the Civil Rights Movements grew. She attended annual conferences like the Regional Council of Negro Leadership, which rallied for voting rights for African Americans.

In 1962, she began taking direct political action in the movement. Hamer traveled to Indianola, Mississippi to take the literacy test and register to vote. Her unsuccessful endeavor resulted in the plantation owner firing her and her husband. Afterwards, Hamer and her family moved around continuously to avoid retaliation from the Ku Klux Klan. After returning to her hometown, she went back to the courthouse to register to vote again. Although she did not succeed, she told the registrar: “You’ll see me every 30 days ‘till I pass.” The third time she took the test, she passed, but when she actually tried to vote, she learned her vote would not count. Motivated by this injustice, she became involved with SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. She taught classes and workshops for them and collected signatures that petitioned for improved voting rights. She became the field secretary for SNCC in 1963.

That same year, on the way home from a conference, Hamer and several other activists stopped at a roadside cafe, but the employees refused to serve them. When they left the cafe, police arrested them, took them to jail, and brutally beat them. Hamer never fully recovered; the incident caused her permanent kidney damage, but she did not let that stop her. She went on to help form the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1964, which challenged the state’s all white delegation that year. She lost the democratic primary, but the televised convention allowed her to bring the Civil Rights Movement to the nation’s attention. In her final years, she helped minorities find work and provide healthcare for their families. She fought for civil rights right up until 1977, when she died of breast cancer. Buried in a memorial garden, Hamer’s tombstone bears her most famous quote: “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Well known figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Thurgood Marshall may receive much more recognition for their roles in Black history, but despite exclusion from lessons in schools across America, these influential people embody bravery, vigilance, and tenacity. Their stories will continue to encourage people to stand up for what they believe in for generations to come.