5 more forgotten figures in black history

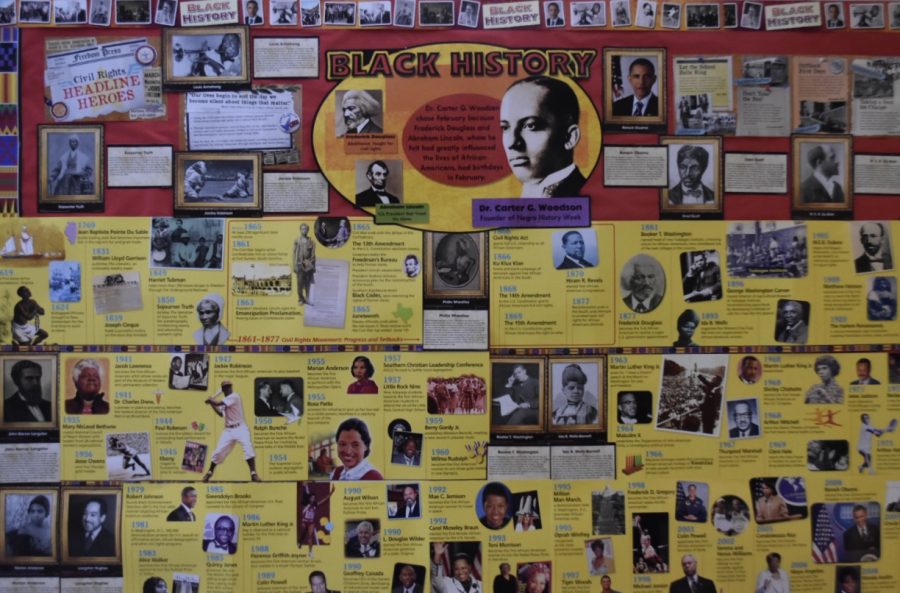

Every February, educators at schools all over America try their best to squeeze black history lessons into their curriculum. At NC, this board placed at the front entrance of the school features a black history timeline, showcasing important African American figures like Sojourner Truth and Barack Obama. Despite this board and the 20-second black history facts shared over the intercom on the afternoon announcements, students (and perhaps adults too) still do not know about the courageous acts of countless “forgotten figures” in black history.

February 24, 2020

“You may do that,” said Rosa Parks when the bus driver threatened to call the police after she refused to move to a seat in the back.

Everyone knows about Rosa Parks and the simple act of civil disobedience that sparked the Montgomery bus boycott. Everyone knows how Martin Luther King Jr. led the March on Washington and delivered his infamous “I Have a Dream” speech to more than 250,000 people; everyone knows about the Little Rock Nine, a group of black high school students who endured a hoard of angry parents every morning to integrate Little Rock High School in 1957. Because these stories and several others shape our perception of black history, future generations will most likely remember them due to continuous reteaching and reprinting. Unfortunately, the stories of several figures in black history never made it to our textbooks.

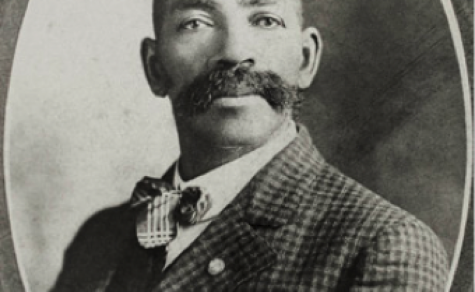

Bass Reeves

Historians believe that black slave-turned-lawman Bass Reeves inspired the titular character from the popular 1949 TV show The Lone Ranger. Born a slave in Crawford County, Arkansas around 1838, Reeves worked alongside his parents as a water boy until he became old enough to work in the fields; when the Civil War started, his owner took Reeves into battle. Historians do not know exactly how it happened, but during the Civil War Bass gained his freedom and fled to Indian territory, where he immersed himself in Native American language and customs, learned their tracking techniques and honed his firearm skills.

After the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, Reeves bought land near Van Buren, Arkansas and became a farmer, and when US District Judge Issac Parker presided over the Federal Western District Court in 1875, he chose Reeves as one of 200 new deputies upon hearing about his knowledge of the area and tribal languages. Reeves quickly earned a reputation as a clever, strong marksman, who brought over 3,000 criminals to justice within his first 25 years as a lawman, including his own son.

During his career, he killed around 20 men in self-defense, saying that he “never shot a man when it was not necessary for him to do so.” A master of disguise, Reeves might even pose as an outlaw himself to outsmart the more elusive criminals. Though he could not read or write, he memorized his arrest warrants and never arrested the wrong person. He became ill and passed away at the age of 71 in 1910. On May 12, 2012, the Bass Reeves Legacy Monument in Fort Smith, Arkansas opened. The statue honors his legacy as the first black deputy U.S. marshal west of the Mississippi River.

Mary Eliza Mahoney

Born in spring of 1845 to former slaves in Boston, Mary Eliza Mahoney knew she wanted to pursue a career in nursing from a young age: at 18, she enrolled in a rigorous 16-month program at the New England Hospital for Women and Children at age 18, and at age 33 Mahoney advanced to the hospital’s graduate nursing program, becoming one of only three students to graduate from the program in 1879.

After she graduated, Mahoney worked as a private-duty nurse for wealthy, white families: her employers usually underestimated her knowledge and skill level and treated her like a regular member of the help. Mahoney fought this by eating her meals separately from the servants and exuding a strong sense of professionalism, diligence and compassion. Mahoney’s reputation raised the standard for nurses of color, and she began receiving requests from clients in the North and Southeast coast.

In 1908, Mahoney co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) with Adah B. Thoms after facing discrimination from the predominantly white Nurses’ Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada (NAAUSC), whose conference members elected her as associate chaplain of the association. Later in her life, Mahoney became an advocate for women’s suffrage, and at age 76 she became one of the first women to vote in Boston after the ratification of the 19th Amendment. Mahoney passed away after a three-year-long battle with breast cancer in 1926. Ten years after her death, the NACGN created the Mary Mahoney Award to give to nurses who strive to break racial barriers in their field.

Robert Henry Lawrence Jr.

Robert Lawrence began training to become the first black astronaut in the US Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory Program (MOL) 16 years before Guion Bluford became the first black astronaut to actually travel to space. Born in Chicago on October 2, 1935, Lawrence graduated in the top ten percent of his high school class at age 16; he then graduated from Bradley University in 1956 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Chemistry. While studying at Bradley, Lawrence joined the Air Force ROTC and became a Cadet Commander. By 21 Lawrence established himself as a talented pilot, reaching a total of 2,500 flying hours. Shortly after in June 1967, Lawrence completed the US Air Force Test Pilot School, and the AirForce selected him for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program.

Unfortunately, on December 18, 1967, Robert Lawrence passed away in a jet crash during flight training at the age of 32, and never made it to space; the other men selected for the MOL program later traveled to space and made up NASA Astronaut Group 7. On February 15, 2020, aerospace company Northrop Grumman launched its new Cygnus spacecraft, the S.S. Robert H. Lawrence, named to pay homage to the first black astronaut.

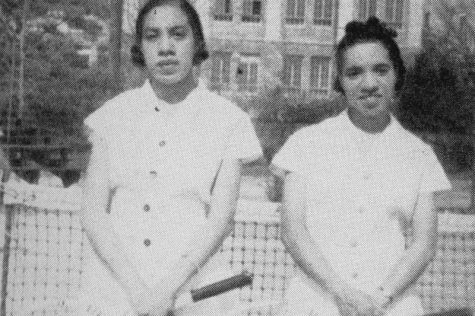

The Peters Sisters

Long before Venus and Serena Williams made their mark, sisters Margaret and Matilda Roumania Peters dominated the world of black tennis. Born in 1917 & 1915, respectively, Matilda and her older sister [Margaret] Rounamania grew up in the predominantly black neighborhood of Georgetown, Washington D.C., where they first started playing tennis on a court covered in sand and rocks. The pair quickly gained a reputation in the neighborhood for their doubles tennis skills, earning the nicknames “Pete” and “Repeat”.

In 1936, the American Tennis Association (ATA) (the oldest black sports organization in the U.S.) invited the sisters to play at their annual tournament. Though they did not win the tournament, numerous historically black colleges and universities saw their talent and offered them scholarships. The sisters each accepted a four-year scholarship from Tuskegee and continued to participate in ATA tournaments while also playing on the school’s basketball team. Both graduated in 1941, and for the next decade accrued 14 doubles tennis titles, becoming well known and admired in the African American community. Roumania also won two ATA singles titles and became the only person to defeat future Grand Slam title winner Althea Gibson at a major competition.

Despite the slice serves and powerful backhands they became known for, segregation prohibited the sisters from competing against white tennis players. The sisters went on to earn their master’s degrees in physical education, eventually returning to Washington D.C. to become teachers. Roumania passed away from pneumonia in 2003, and Margaret passed away the following year. The plaque at the Rose Park tennis courts (now called the Margaret Peters and Roumania Peters Walker Tennis Courts) where the sisters practiced as children, states that the “community is proud to honor and remember the legacy of these pioneering, African-American women from our neighborhoods.”

Americans manage to keep the legacies of well known African Americans such as Harriet Tubman, Jackie Robinson and Booker T. Washington alive by watching documentaries about them and studying them every February. The aforementioned figures, while regarded as influential for their groundbreaking contributions to black history, typically overshadow lesser-known trailblazers. While it may seem impossible to remember every single black person who ever succeeded in making a difference, legacies live by celebrating the progress they helped make and adopting their principles to guide how we live our lives.