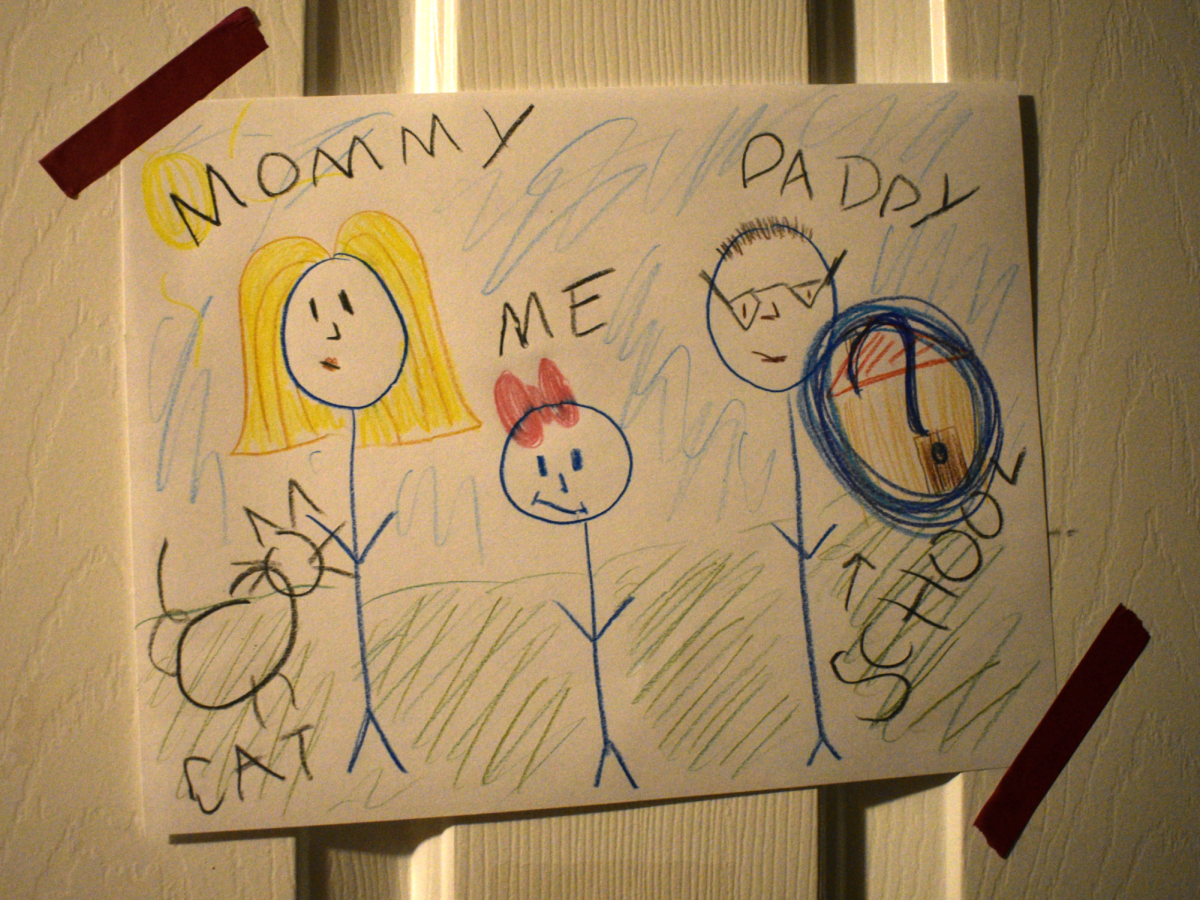

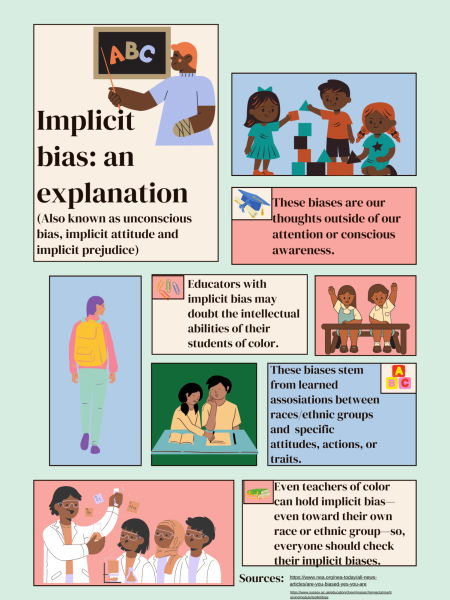

Known for their curiosity, imagination, innocence and laughter, children remain the most vulnerable group in society. As they head into the real world, they will inevitably make mistakes and cause trouble; this inevitability requires parents, teachers and any adult who engages with children to know that the responsibility to educate and guide the youth falls in their hands. Unfortunately, implicit bias reigns in the minds of adults in education, causing them to find trouble in the innocent actions of Black and Hispanic children and harshly discipline them.

May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled on the notable Brown vs. The Board of Education case, overturning Plessy vs. Ferguson and ridding the notion of separate but equal. Students of color paved their way into previously segregated schools, establishing their right to the same educational opportunities as their white counterparts. Nonetheless, the hundreds of years of racism and inequity would not cease immediately. Despite the Constitution and laws declaring all students equal, Black and Hispanic students continue to face challenges in education today, which ultimately lead to disparities in the school system and beyond.

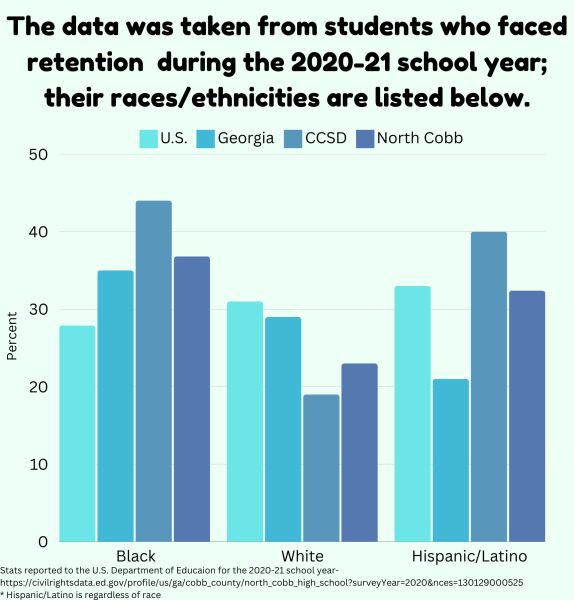

Pulled from state data taken from the 2020-21 school year, 36.6% of all PREK-12 students in Georgia identify as Black and 37.5% identify as white. Given the similarities in the enrollment of Georgia’s Black and white students, an equal, implicit-bias-free educational system would mean that the statistics regarding their discipline and retention rates would not bear any drastic differences.

However, given the U.S.’s history with race and education, this idea of an equal system does not stand as realistic in the U.S. As a result, Georgia and its school districts, including the Cobb County School District (CCSD) present obvious disparities between minority students in comparison to their white counterparts.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, of the nearly 3000 PREK-12 CCSD students who repeated a grade—also known as retention— in the 2020-21 school year, 40% of them identified as Hispanic/Latino, and 35.2% identified as Black. For those familiar with the district, these statistics may not seem shocking due to CCSD’s racial makeup. After all, Black students compose 30.5% of CCSD’s population, with Hispanics trailing behind at 23.7%. However, to determine if these statistics prove significant, one must examine their rates in comparison to white students. White students still exist as the district’s most populous racial group—as 35% of the district’s students identify as white, — yet their percentage for retention stands at 18.9%, far lower than Black and Hispanic students. If white students summarize the plurality in the CCSD, why do Black and Hispanic students account for nearly 75% of the retention, while white students do not even amass 20%?

Ultimately, various reasons exist for why a student, regardless of color, may repeat a grade. Commonly, the student does not meet the requirements and progression needed to advance to the next grade level. To learn the course material, a student needs actually to attend class, however, when Black and Hispanic students face barriers to access to education, this becomes troubling.

Recently, California passed the “Too Young to Suspend Act” which, in essence, banned schools from suspending and expelling preschoolers and kindergartners. California’s Black and Hispanic youth began missing too much school due to the influx of punishments that resulted in time away from school. In fact, in the 2017-18 school year, Hispanic California students missed 382,769 days of school due to out-of-school suspensions—composing 55.4% of all the days of school missed in California. Furthermore, despite only making up 5.5% of all California school enrollment in the 2017-2018 school year, Black California students accounted for 17.5%, missing 123,273 days of school that year due to suspension. This means that despite the fact that white students account for four times the population of Black students in California, there lies a less than two percent difference in their days of suspension. Ultimately, if school districts such as those in Georgia want to attack the problem of retention rates for minority students, they will need to focus on allowing minority children to stay in school, particularly through acts similar to those established in California.

Given that minority children face punishment both more harshly and more frequently, one must ask the daunting question: are Black and Hispanic students simply more troubled than white students?

Nearly a decade ago, the Yale Child Study Center shared a study that shined a light on the implicit bias that educators hold about their students, particularly Black boys. The experimenters asked 135 teachers to watch a video of a Black boy, a Black girl, a white boy and a white girl playing together. The researchers then told the teachers to find the misbehavior in the video, however, the preschool children did not truly misbehave. While the subjects simply looked for misbehavior, the study used an eye-tracking feature to determine which student the teachers looked to when looking for misbehavior. An overwhelming 42% of the educators observed the Black boy most closely. This illustrates that Black students do not misbehave at a higher rate than their white peers, rather, educators observe Black boys more closely due to their implicit biases toward the Black youth.

“When it comes to implicit bias, sometimes folks aren’t necessarily looking for it, but they have no filter for it when it happens. So there were many times in my classroom when I had Black students, they may say or do something that, culturally, I could understand what it was, and I could join in on the joke. A white teacher sees the same thing and they are trying to discipline them for something when they didn’t even do anything bad. They don’t have a filter to differentiate them being mischievous, from them being funny. But, it’s the teacher’s responsibility to have that filter,” Educator Ruth Jones said.

Currently, to obtain a teaching certification, no federal qualification requires teachers to take any courses regarding children’s races in education. Additionally, Georgia teachers—among teachers from almost every other U.S. state—do not receive implicit bias screenings nor counseling to ensure they provide a safe and equal environment for all students, regardless of color. If educators hold implicit racial biases, educational institutions and policymakers will need to set the agenda to include methods to rid implicit bias and create an equitable environment for young Black and Hispanic students that although the U.S. has legally promised, they have still yet to provide the framework for.

Truly, the complexities of public policy make policymaking an achievable yet difficult goal. Teachers who teach in diverse areas such as the CCSD do not need to wait for policies from their local, state and even federal government. To effectively attain an equitable environment for Black and Hispanic students, teachers need to check their own implicit biases on their students and do the work needed to ensure every child feels comfortable and equal when walking into a classroom.

“I think they [the teachers] have to understand the communities that they are going into. If I know that I’m coming into a community that I don’t know about, and I’m about to engage with a culture that I don’t know about, it is my responsibility to learn about it…, I may need to find some educators who are from that community to give me some advice. Or, I need to ask my students or do cultural projects with my students to understand more about the places they are coming from. Or, I invite their families into the classrooms so I can better understand them, right? You do have to be thoughtful about it…to ensure that all of your students feel welcomed and that you all understand each other,” Jones said.

The effects of neither solving nor acknowledging racial biases in the classroom do not only result in viewing Black and Hispanic children as troubled. In fact, in 2020, the College Board released data that showcased the differences between Black and Hispanic math scores from their white counterparts—all students identified as seniors in high school. Out of the 800 total points, one can score in the math section, Black students, on average, scored 454, and Hispanic students scored 478. On the other hand, white students boasted a score average of 547. This means that nearly 60% of the white test takers met the benchmark to be on track for college while less than 25% of Black test takers and less than 35% of Hispanic test takers also met the same benchmark. Given that these students—prior to the test-optional policy that college admissions use today—would need to submit their test scores to colleges; this put Black and Hispanic students at a disadvantage on the path to seeking higher education.

“We should have more people in office and have more people who are higher up who are of color or who are from different cultures. They can advocate for [people of color] and explain why groups of students act the way they do, and the differences in the way that students act.[For test scores,] the education has never really been tailored to us. So, I guess we are kinda learning something foreign. And it shows up in our scores,” magnet junior and Black Student Union president Mikiyah Spotwood said.

Outside of the school doors, Black and Hispanic children already face higher amounts of implicit bias within the criminal justice system, the healthcare system and other systems that determine their quality of life. As young students of color enter the doors of their classrooms, they should enter a space where they can learn freely, without the daunting implicit bias that takes over their everyday lives. To remove these hurdles that slow down Black and Hispanic youth from achieving equality, teachers, students, parents and all adults who contribute to the success of a child’s education must collaborate to rid their implicit biases and learn about the communities they educate.