From William Shakespeare and Charles Dickens to Stephen King and Colleen Hoover, ever-changing styles, rules and dialects impact the continuously developing English language. As technological advances and media cycles transform language, different ways of communicating shroud linguistic history. Cursive disappearing into print and formal tongue-to-slang stand as characteristics of a constantly evolving modern language. As current students advance in their schooling, they receive exposure to various languages and they must face the everlasting impacts of novel technology on pieces of history.

Old English, defined as the language spoken and written in England before the year 1100, emerged from Anglo-Saxon roots. A predecessor to Middle English and the current Modern English, this Germanic-derived tongue displays a staggering difference from the English language seen and spoken in the U.S. today. English language courses across the nation use historic works to enhance their curriculum and teach older ideas, but, as language changes, these pieces become increasingly difficult to decipher. Current students find it difficult to understand old works of literature with older English patterns of scattered word order and extensive vocabulary, unusual to the organization seen today. The gradual yet constant evolution — recognized as a complex system — requires the alterations of three main ideas that modify the face of language: transmission, generation and location.

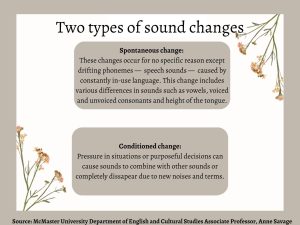

“English starts in a bunch of dialects that were quite different from one another, possibly not mutually intelligible. If we go back even further to the Indo-European language family, and realize that once there were 12 different language groups there… somehow the dialect spread out. And, of course, people were not mobile like we are now — and when you put people in a place and isolate them, they change without knowing it… Language is fluid, and it’s always a moving thing. Our vocal apparatus is moving but also our culture is moving and we need new words for things,” McMaster University Associate Professor of English and Cultural Studies Anne Savage said.

Exposure to various types of speech plays a major role in language acquisition. While remnants of the Anglo-Saxon language remain in American vocabulary today, the manner in which people accurately grammatically craft sentences today differs from historical origins. As individuals interact, they borrow words, sounds, sentence structure and other mannerisms from various languages and cultures. Simply speaking to a person from a separate region or background can subconsciously impact one’s own language. This subconscious change can even become recognized in today’s society with the help of trends. One individual may start a new fad over a witty word, and soon enough his/her entire school adds the term into their vocabulary. These transfers of language tend to occur in the subconscious mind, through observation and trends — the community that surrounds a person majorly influences his/her individual thoughts and perceptions.

“[The change] might have happened because English during the 12th century started borrowing so many words from Latin and so many words from French. The Old English vocabulary lost about 80% of its words. When writers were writing, they were often translating English into French, and then Latin and French into English. They started just taking the words, so we started getting Latin and French words. Once we’d started this borrowing habit, English didn’t just stop borrowing. One of the big changes for Olde English in sound was the Norman Conquest in 1066, English is the earliest vernacular written language in Europe. We have writing from the seventh century — the sixth century even — so that’s good for us because it helps us chart,” Savage said.

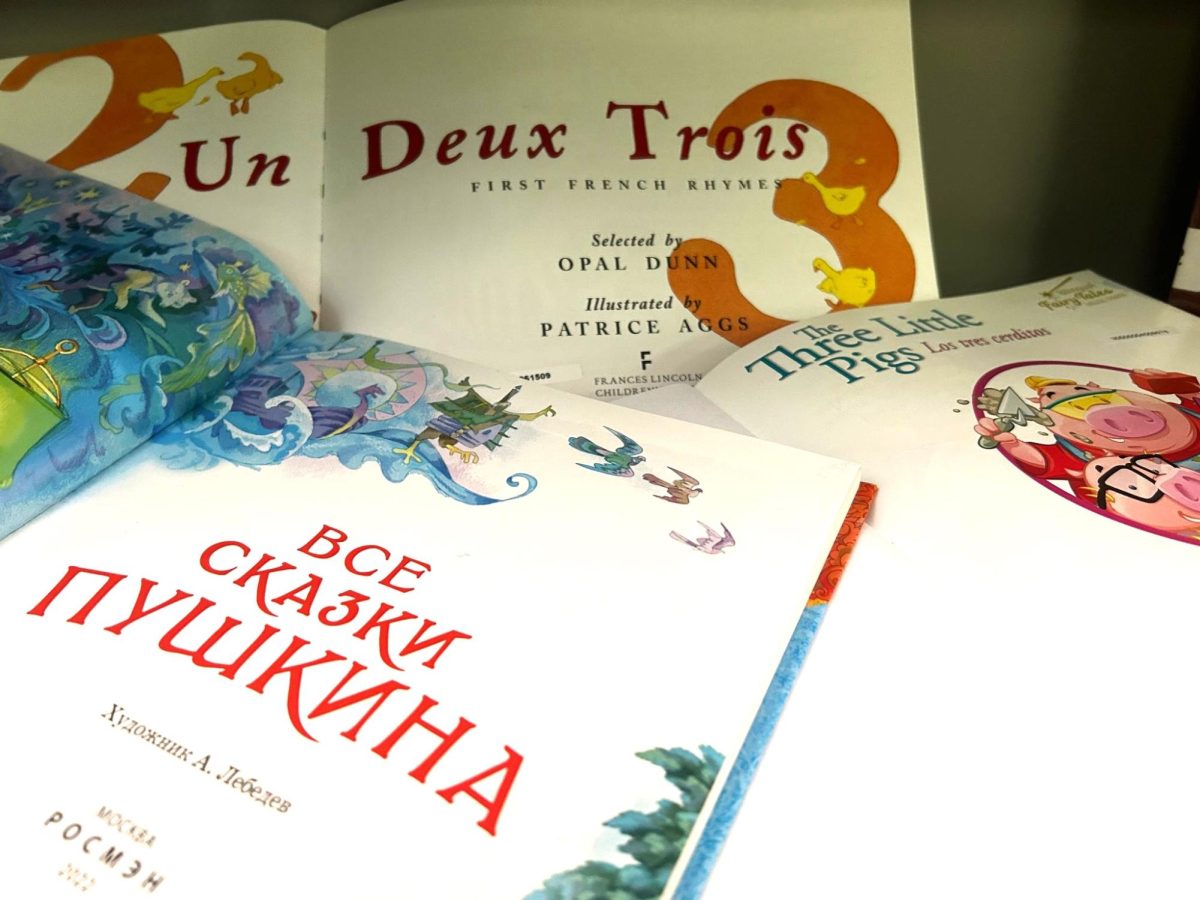

Similarly, language passes down through family traditions. Different generations will introduce new ideas based on historical events and developing technologies, causing linguistic styles and preferences to alter. Similar to how fables can alter and change as they pass down in a given family tree, language acquisition occupies moving parts and pieces. For example, various households across the U.S. speak multiple languages, predominantly Spanish. One in five U.S. households speaks a secondary language to English, showing the effect of parents raising their children in multilingual homes. These linguistic trends alter speaking patterns when speaking English, causing languages to blend such as Spanglish due to slip-ups and combination words between two cultures and mother tongues — which can become further accelerated through language sharing in online platforms. Additionally, the sheer location of an individual can affect linguistics: Geography and region create communities that isolate behaviors and speaking trends.

With recent pushes of technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots and assistants, information possibly not heard or seen before can become easily shared and accessed across the world. This eliminates the burden of location for sharing information worldwide. This accessibility explains how conversation has evolved from proper sayings and settings into casual terms and slang. With words shortened and put together to form new meanings, different regions and groups of people recognize different forms of slang and dialect. With people from Southern states repeatedly using “y’all” and Canadians cutting their “o” sound short, language proves itself an entirely diverse subject.

“Language changes differently in different places, which is the reason that you can recognize that someone is from Britain as opposed to America. American English has just changed differently than British English. You can probably recognize somebody who comes from the state of New York — that they don’t sound like they’re from around here. You can make a conscious decision, but usually you don’t. Usually, you’re just following along with what you hear around you and what makes sense to you. Language is very situational,” University of Georgia Professor in Humanities, Department of English Fellow Bill Kretzschmar said

Similarly, when written language first developed around 3200 BCE, cursive — or script — stood as the primary form of daily writing. However, one may now imagine script in a completely different way than it historically appeared. The older forms of cursive underwent intense transformations before resulting in the loops and swirls it traces with today. A 2012 study conducted by The New York Times showed that a majority of individuals wrote in combined handwriting with elements of both cursive and print. Slowly altering through the different eras, this new take on an old form of penmanship quickly became the dominant form of communication, establishing its importance across the world.

“I learned cursive in second grade and always used it up until the sixth grade. It was then that I found out my teacher could not read cursive, so I had to relearn print. Simply because many people cannot read or fully understand cursive, I don’t think it proves a necessity for children to learn. I have noticed a change in the importance stressed with children learning language. Firstly, from an international sense, I feel that children, especially in American schools, do not receive pressure or advice to learn another language, even though it could be a helpful thing to have later in life. Second, I think language overall in school has become more lenient, and certain kids do not end up writing well due to lack of preparation,” senior Henry Witschy said.

Today, schools determine the criteria taught in a classroom through a guideline application known as the Common Core State Standards. This initiative outlines a specific curriculum to ensure learning goals — but states control the lessons required. These standards include the required skills for each grade level in K-12 schooling, but cursive has faced a recent decline in mandate. Debate over whether cursive actually appears in guidelines significantly contributes to confusion regarding writing lessons.

Because the requirement differs depending on the state, numerous reporters claim cursive appears in guidelines while opposing organizations believe teachers hold the power to determine whether to teach it. Due to the lack of state assessment regarding cursive — especially in grade three when teachers typically introduce the art— advisers push script into the shadows. This creates teachers’ panic to squeeze the needed handwriting lessons between the required syllabus instructions: without receiving classroom time, the bends and loops fade out.

An incentive for this alteration in curriculum stems from shifts to technology and typing. Learning how to navigate the endless forms on online websites and programs such as the various computer systems including Microsoft Windows and Google takes priority over perfecting handwriting with several tests such as the ACT, SAT and AP exams transferring to online formats. This technological focus, notably the time spent on typing practice, overwhelms the long process of teaching cursive, leaving teachers with limited time to instruct basic handwriting.

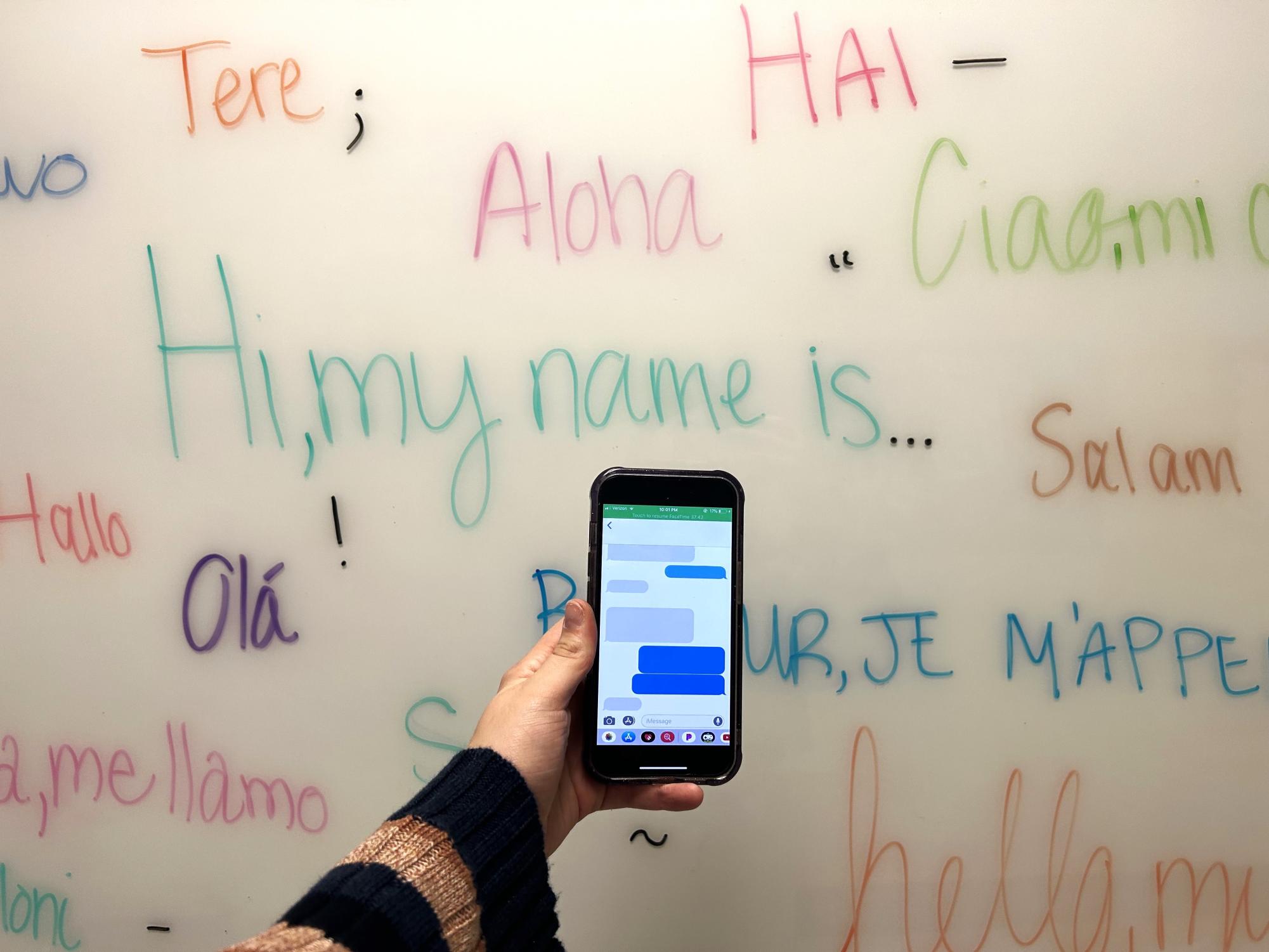

Similarly, technology has advanced prominent verbal processes over decades. While telephones, Alexander Graham Bell’s revolutionary invention helped pave the way for the 1800s, current improvements to older innovations have only intensified the effects of the technology. Smartphones — frequently found hidden in the pockets of adolescent Americans — provide easy access to technology and the World Wide Web with the click of a button. Messaging apps such as iMessage allow individuals to connect instantly through a chat screen, sending instant messages and halting the historic trace of letters sent for mail transit. This ease of sharing information alters the recognized dominant form of real-life speech. Historically, aside from face-to-face conversation, letters acted as the prominent secondary form of language transfer. However, with the introduction of texting and phone calls, a whole new world full of acronyms and short bubbles became a go-to for the transfer of ideas.

Telecommunication — the exchange of information through online means — completely shifted written and spoken language. From slang terms to FaceTime, the way humans interact has evolved from letters and conferences to speaking on a phone. Social media allows the quick and easy transfer of new words and trends, pushing several minuscule changes at a time. These changes, insinuated by social media, occur in split increments; for example, videos and images posted for attention may take weeks or months before they become viral — these growing pains cause delays in alterations. When experiencing day-to-day life, however, these adjustments within words and phrases show just how far information can spread in a limited amount of time.

“In my daily life, I use a lot of slang because it is either derived from my family, because I’m Haitian, or the places I’ve lived in growing up like Macon, New York and Sandy Springs. It is a little bit of both [picked up and conscious slang] but the new slang is very corny nowadays, so if I say it I say it as a joke — but the slang I picked up growing up is an everyday thing. Social media is very hard to know if things are true, but I mostly use it to get info about music,” junior Rashon Dixon said.

As online platforms spread across generations, novel technologies change the way people speak, write and even think. Humans continue to look for ways to polish the transfer of information and opinions, and technology helps in the conversion. Linguistics will always face alterations, parts of it quick and parts of it gradual, and even humans several centuries from now may not understand the words individuals today write and speak.