The Standardized Aptitude Test (SAT) remains a key factor in college admissions. Invented in 1926 by Carl Brigham whose motivation for creating the SAT stemmed from his unruly belief that American intelligence declined due to waves of immigration from Eastern Europe. Colleges use the assessment to assess the academic abilities of students. However, colleges rely on the SAT for student admissions and the test should not determine one’s future.

Standardized testing evolved since the end of World War One as a way to determine a student’s ability to handle college material. Inspired by his work with the army, Brigham invented the SAT, which he evolved from the Army IQ screener. Although the past testing process differentiates from today’s; the test’s fairness remains a contentious topic. Approximately 60% of Americans believe the SAT should not solely determine college acceptance which explains why 80% of today’s colleges do not require the SAT for admission.

By as early as 1935, Harvard University made SAT scores a mandatory requirement for admission, solidifying its role as a decisive factor in determining students’ eligibility for higher education. However, SAT-opposers still wonder if the SAT truly fulfills its intended purpose, or if it acts as a barrier to educational opportunities.

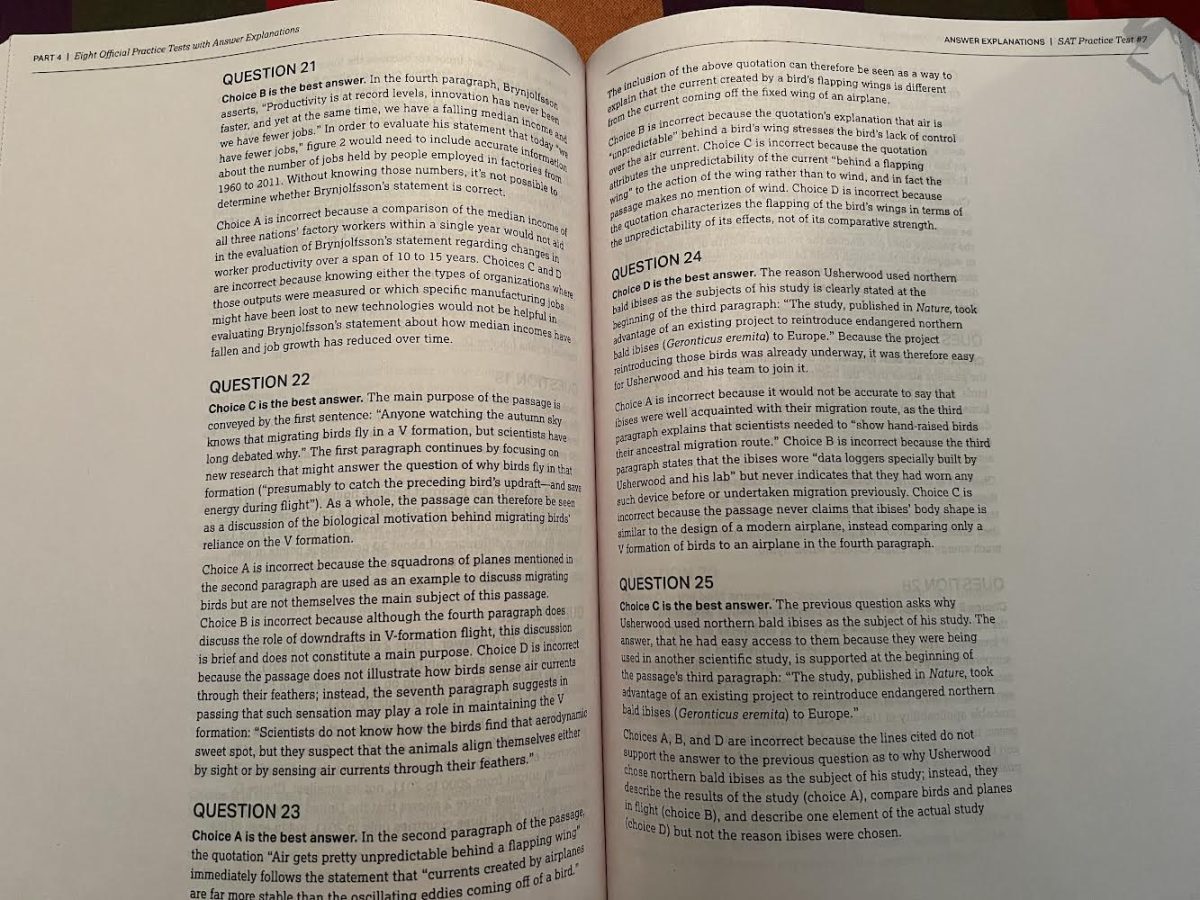

Critics may argue the SAT withholds no bias, stating preparation leads to a higher score. Certain statistics prove this point with the Preliminary Scholastic Aptitude Test (PSAT); students learned that taking the PSAT can prepare students for the test as they share similarities. Students may experience a growth of at least 139 points due to pre-preparation. This claim, however, fails to explain why richer families statistically score higher on the SAT than others and why the average scores for African American students taking the SAT remain significantly lower than white and Asian students.

Less than 80% of high-ranked universities require SAT score submission. The score, which ranges from as low as 400 to as high as 1600, combines two sections: reading and math. Notably, this test does not evaluate life skills, aspirations or common knowledge. Instead, it focuses on reading, writing and math proficiency.

The statistical differentiation causes students to believe they should not continue the SAT. In 2020, African American students scored an average of 454 in the math section, while their white and Asian counterparts achieved significantly higher scores, reaching an average of 530. African American test takers in 2022 held an average score of 926 and American Indian or Alaska Native students held an average of 936, while white and Asian test takers scored an average of 1098. The racial gap between SAT scores remains prominent and visible as time continues.

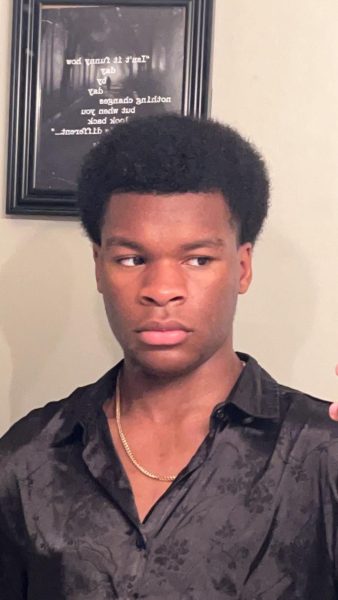

“I feel like [the school] could’ve better helped prepare me for [the SAT]. They could’ve given me tools instead of just telling me ‘Oh yeah take your SAT.’ Most of [the SAT] is like foreign things, but some of Algebra II was in it. I feel like richer families statistically have higher SAT scores because their parents may have gone to college and also because they have the money to hire tutors and get more resources,” senior Godwin Fini said.

Over the past 20 years, the gap between white and African-American students’ scores remains persistently wide and unchanged. This enduring statistical discrepancy serves as the primary argument against the fairness of the SAT as an assessment tool.

“If I had to say why richer households on average have higher SAT scores, it’d be the obvious [white people]. They have more money [In America], so they can afford a better education, but that’s not the only reason. Hard-working students wouldn’t struggle on the SAT for a number of reasons, but at its core, it’s because they have run through the information so much that it’s ingrained in them,” senior Ezekiel Cotton said.