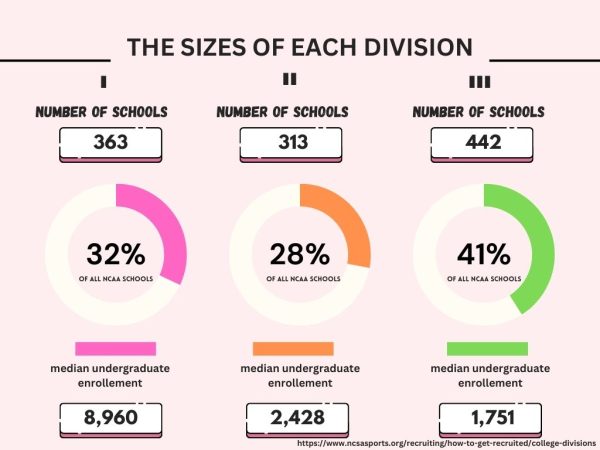

Spanning across the United States, the dreams and ambitions of numerous college student-athletes converge under the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). This governing entity orchestrates the intricacies of collegiate sports, providing a structured framework for institutions put into its three distinct categories: Division I (DI), Division II (DII) and Division III (DIII). The delineation of NCAA divisions ensures fairness, fosters competition and creates a platform for schools of varying sizes and resources to participate in collegiate athletics.

With the increasing concerns over the safety of college football, the NCAA held a meeting in 1905 led by President Theodore Roosevelt to address the country’s worries. Initially known as the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States, the NCAA adopted its name in 1910 and has since evolved to organize national championships, commencing with the National Collegiate Track and Field Championships in 1921 and expanding to include basketball in 1939.

In the aftermath of World War II, the NCAA recognized the need for standardized regulations and responded by adopting the Sanity Code in 1948. This set of guidelines strongly emphasized financial aid, recruitment and academic standards to preserve amateurism in college athletics. The appointment of Walter Byers as executive director in 1951 marked a shift towards professional leadership, reflecting the evolution of NCAA responsibilities.

Financial allocation within the NCAA’s divisions remains a critical determinant of the scope and scale of their athletic programs. DI schools devote substantial financial commitments to elevate their athletic programs. Institutions allocate a significant portion of the budget to coaching staff salaries, state-of-the-art facilities and athletic scholarships. For instance, University of Georgia (UGA) head football coach Kirby Smart signed a contract extension through the 2031 season, with a salary of $10.7 million and $1.3 million in bonuses for the current year. This investment serves as an incentive to attract and retain top-tier coaching talent and athletes, enhancing the competitiveness of the programs.

In DII, institutions distribute investments across coaching staff salaries, facilities and program development. While coaching salaries in DII may not reach the figures seen in DI, they remain competitive to attract skilled coaching staff. This approach enables DII schools to sustain a strong athletic presence without enduring the same financial pressures as their DI counterparts. DII schools annually receive 4.37% of NCAA revenue sources, contributing to the budget’s alignment with the association’s ten-year financial plan, strengthening championships, distributions to memberships and other initiatives.

DIII takes a distinctive approach, prioritizing a holistic student-athlete experience over high-stakes competition within the constraints of modest budgets. Institutions direct finance toward academic support, community engagement and fostering a well-rounded athletic experience. Coaching salaries, while competitive, do not reach the levels seen in the other divisions. The emphasis here lies on personal and academic growth alongside athletic achievement, aligning with the broader mission of DIII institutions. The division annually receives 3.18% of NCAA revenues, with approximately 75% of the budget devoted to supporting the division’s 28 national championships. The remaining 25% supports member schools and conferences through non-championship programming and educational resources.

Financial disparities do not only exist across divisions but also within divisions. Mere participation does not secure a position among the top revenue-generating institutions. Within DI specifically, schools encounter substantial financial variations that reflect diverse revenue streams and fundraising initiatives.

“For 2023-2024, UGA’s operating budget is approximately $175 million; Georgia Tech’s is $125 million; and Georgia Southern and [Georgia State] are approximately $36 million each. Both UGA and GT receive approximately $50 million for their conference affiliations. [Georgia Southern] and [Georgia State] are in the Sun Belt Conference and we receive $2.5 million. As long-time athletics programs, both UGA and GT pull more than $15 million from endowments, historical assistance that we do not benefit,” Georgia State University Director of Athletics Charlie Cobb said.

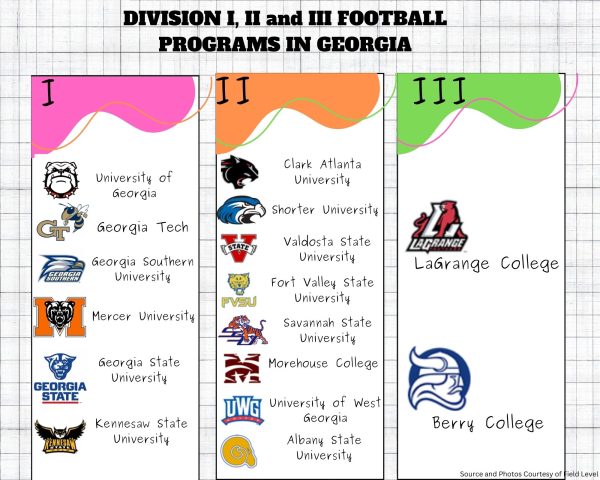

The variety in training facilities, stadiums and practice spaces highlights differences among collegiate athletic programs. Sanford Stadium, the home of the UGA Bulldogs, epitomizes DI football, boasting a net worth of $71 million accumulated over the years and providing seating for 92,746 fans. In contrast, the University Stadium at the University of West Georgia—a DII football program—accommodates 10,000 spectators with a net worth valued at $29 million.

In addition to the allure of Sanford Stadium, the UGA football training facility symbolizes the commitment of DI programs to provide frontline resources for their athletes’ development and performance. With an $80 million investment, this complex serves as a one-stop shop for college football’s top stars. It features an upscale locker room, players’ lounge, weight room and unique amenities such as a sports bar and demo kitchen. Moreover, it houses a barbershop and a sports medicine facility complete with hydrotherapy, sensory deprivation and cryotherapy.

Both DI and DII institutions extend athletics scholarships to student-athletes, with DI providing full-ride scholarships in certain sports. For instance, DI Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) teams can offer a maximum of 85 full-ride scholarships, while DI Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) programs can furnish up to 63 scholarships. Nevertheless, institutions can only provide full-ride scholarships in only a handful of sports, leaving several student-athletes to receive partial scholarships The average athletic scholarship in DI hovers around $14,270 annually for men and $15,162 for women.

In DII, student-athletes secure partial athletic scholarships, combining them with financial aid acquired through academic achievements, need-based grants or student loans. The average athletic scholarship in DII falls lower than DI, tallying approximately $5,548 annually for men and $6,814 for women. In stark contrast, DIII schools do not supply athletics scholarships but provide financial aid packages for non-athletic criteria. Despite the absence of athletic scholarships, DIII institutions recruit student-athletes and afford opportunities for participation in intercollegiate athletics.

“The large financial agreements benefit the 1-2% of kids, so most should still make their college decision based on team chemistry, fit with offensive and defensive systems, can I play for this coach, and does this school provide me with an academic major and other resources to gain a quality education (and diploma) that will change my life. Unfortunately, that is not happening on many levels and this is not good for the kids or the college system as a whole,” Cobb said

Across NCAA divisions, athletes obtain notable experiences, showcasing the diverse nature of collegiate sports. An athlete’s journey remains not solely defined by their division; individual factors such as coaching staff, team culture, academic opportunities and personal goals contribute to an athlete’s experience. Additionally, the nature of the sport itself plays a crucial role, with differences in training programs, competition schedules and team dynamics shaping each athlete’s journey.

“I will be going to Berry College for football starting in the Fall of 2024. The workouts I will be doing over the course of the season will focus more on building muscle but also on making sure I am healthy. The training facilities at Berry are still very nice compared to other Division Three schools. Division one schools, however, just have more money and more state-of-the-art ways for athletes to train and recover,” senior linemen Zachary Addison said.

While inequalities exist over the divisions, institutions can implement various solutions. Firstly, ensuring that each division obtains access to modern training facilities, equipment and resources can diminish disparities. This could involve NCAA officials allocating funding for facility upgrades and training resources. Promoting media coverage for lower division sports can increase visibility and recognition for athletes competing at those levels, providing them with similar opportunities for the same chance for exposure and recognition as their DI counterparts.

With the recent introduction of Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) deals, athletes across each division can monetize their brands. These NIL deals provide athletes with financial gain and avenues for exposure, potentially attracting sponsorships and endorsements that can contribute to the financial health of their teams. This additional revenue stream can increase team budgets, allowing for further investment in training facilities, equipment and other resources that ultimately benefit the entire athletic program.

Implementing stricter regulations on athletic scholarships and recruiting practices can help ensure that institutions compete fairly and prevent wealthier schools from gaining undue recruiting advantages. For example, the NCAA could consider imposing limits on the number of athletic scholarships that DI schools can provide, thus preventing schools with greater budgets from stockpiling talent. Additionally, allocating financial resources specifically designated for recruiting purposes to DIII schools could enable them to attract better talent and compete more effectively with their DI and DII counterparts.

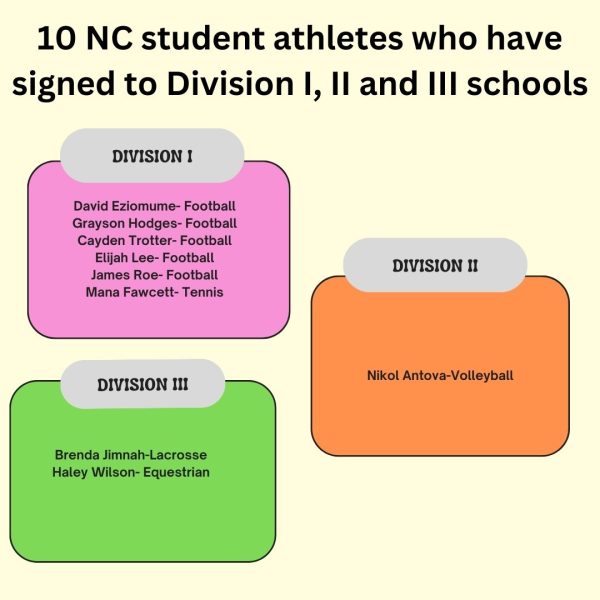

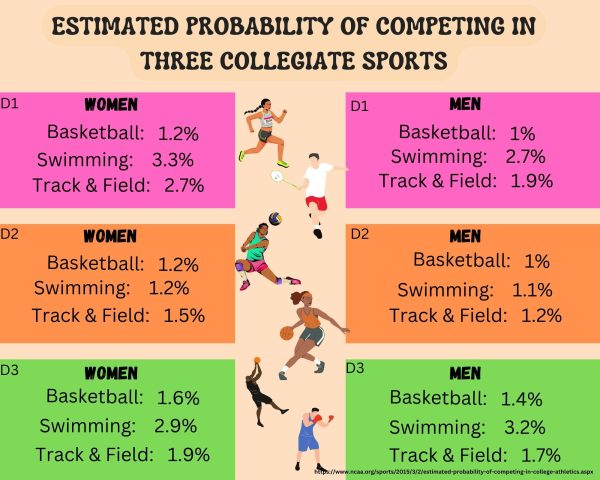

While countless student-athletes possess the dream to play their sport at the collegiate level, they should understand the great difficulty converting their dreams to realities can pose. Students obtain an estimated probability between 0.7% and 5% of competing DI in their sport. Roughly eight million students currently participate in high school athletics and only 6.6% or 530,000 of them continue to play in college. NC students, however, have proven successful at chasing their dreams. Over 20 NC class of 2024 graduates have signed across the NCAA divisions to their respective sport.

“We all must live within our means, so we make strategic decisions that benefit our student-athletes based on what we can afford. We preach our culture of success and operate with our three core values in mind daily. Coaches are still trying to recruit outstanding players, but the current environment says to recruit transfer players in addition to high school student-athletes. Across the country, the student-athlete experience is becoming more transactional and that’s not a good thing,” Cobb said.

While the systemic disparities in collegiate athletics may not disappear overnight, concerted efforts can pave the way for meaningful change. By prioritizing equity and fairness, schools within the NCAA can work collaboratively to create an empowering environment for all athletes. By fostering a culture of inclusivity, colleges around the U.S. can lead the way in shaping the future of college sports, ensuring that each student obtains the opportunity to succeed, regardless of their background or division.