Ballet: a graceful, elegant form of art that various countries and people participate in. The form began in Italy during the 1500s, where nobles would learn the sophisticated moves and perform them during celebrations such as wedding feasts. Ballet continued to develop during the 16th century when Italian royal Catherine de Medici married King Henry II and introduced the practice to the French courts. In France, King Louis XIV popularized ballet and even performed various roles himself in productions. Under his reign, a dance academy opened in Paris in honor of the nation’s love for ballet. This academy eventually opened stand-alone ballet performances to the public.

These performances grew worldwide, and in the 1700s, Peter the Great of Russia began to replace Russian folk dancing with ballet performances in his attempt to westernize the country. Multiple dance schools began to appear in Russia throughout the century as the art spread worldwide.

While the dance form continued to expand internationally, a Russian dancer named Agrippina Vaganova (1879-1951) revolutionized the world of ballet. Vaganova danced at the Imperial Russian Ballet and studied under French teacher Marius Petipa. During her time at the studio, Vaganova comprised the Russian principles she learned with the influences of Petipa and her knowledge of technique from famous Italian ballet instructor Enrico Cecchetti. In merging these principles, Vaganova created the prevailing Vaganova technique that continues to direct dance studios today: such as the various ones that NC students and adolescents attend in the surrounding Kennesaw area.

Vaganova began her career in 1916, teaching her students her new technique. She documented her method in the book ‘Basic Principles of Classical Ballet’, which broke down the fundamentals into different sections. Each chapter dedicates itself to a different group of essentials such as arms, movement of the legs, the eight body positions, jumps and pointe work. Ballet pedagogues around the world continue to use this novel today to operate their teaching style and to gain a deeper understanding of the style.

One example of this influence that Vaganova inspired, the barre system, became a critical part of studios worldwide. The barre exercises activate specific muscles such as the glutes and abdominals to build strength so the dancer can incorporate the movements they learn into dance performances. As the barre increases strength and proper technique with the support of the barre, it also prepares a dancer’s muscles to practice the same movements in the center portion of the class. In the center, ballerinas learn a combination of steps they practiced at the barre. Choreographers may then incorporate these steps into performance pieces such as recitals or shows like the infamous The Nutcracker. Along with this impact on teaching, Vaganova also influenced the performance aspect of ballet classes.

“While Vaganova was still teaching, she produced one brilliant dancer after another. The results of her teaching method could not be denied. She wrote a book, “Basic Principles of Classical Ballet,” detailing her ideas, technique and way of teaching, and the Leningrad Choreographic School named its school after her. With this book and her former students preserving and continuing her methods, the Vaganova style has become one of the leading methods of training dancers and continues to produce some of the best dancers in the world,” Impact Dance of Atlanta ballet teacher Amanda Neeley said.

This teaching method not only influenced how instructors teach dance lessons but also how teachers and choreographers plan performances. Dancers learn moves during class that they will eventually perform in shows or recitals. The approach uses the idea that a dancer will continue learning increasingly challenging moves only when they master previous skills adequately. Previous dance teachings included teachers continuously expecting students to perform higher-challenging moves, so this idea opposed that view by waiting for students’ skill levels to develop.

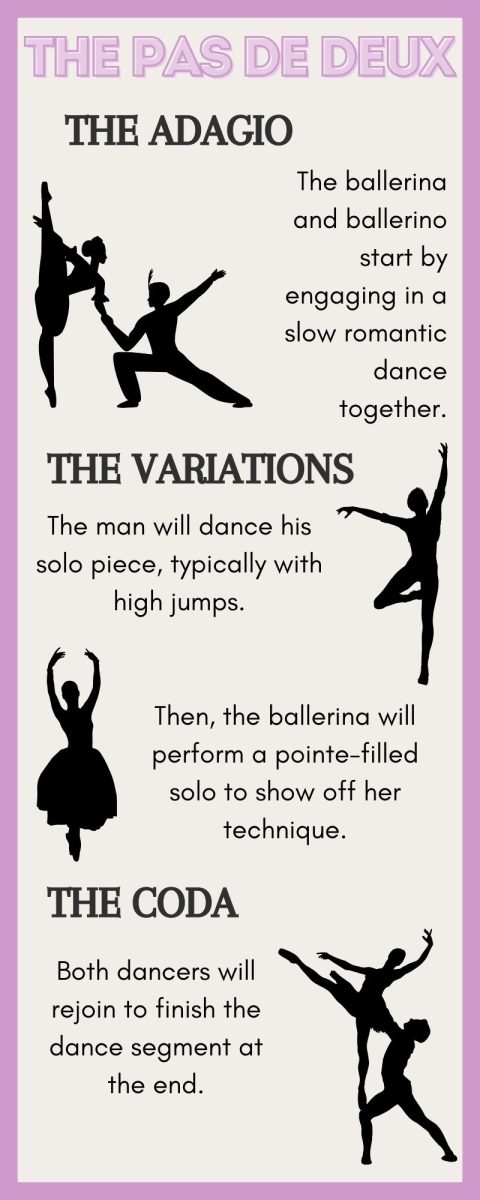

Vaganova additionally emphasized the Pas de Deux in performances. The Pas de Deux, meaning “step of two” in French, displays two dancers as a section of a ballet performance. The two dancers, typically a female ballerina and a male ballerino, begin dancing together in an adagio piece. The adagio, meaning “slowly,” encompasses a romantic duet in which the woman and the man dance together closely throughout the first section of the piece. The ballerina engages in abundant pointe work while her partner supports and frequently lifts her. Afterward, the couple separates and each performs a solo piece called a variation. Typically, the male dances first and performs numerous jumps and grandiose movements such as a Rivoltade to travel across the stage. When his variation ends, the female will dance next. In her variation, she will display quick pointe movements and turns such as Chaînés to show off her technique. The dancers will reunite at the end and perform another duet to finish the piece.

Vaganova believed all work during ballet training should ultimately prepare dancers for this duet piece. She believed it to demonstrate the various ballet moves and techniques a dancer needs, which reflects her ideas of strength training and building each move a dancer learns on top of another.

Ultimately, Vaganova used her class as a way to teach dancers the specific characteristics that would eventually lead them to the Pas de Deux she emphasized. These specific attributes encompass what Vaganova takes her infamous ballet style’s fame from.

Other attributes that characterize Vaganova’s style contain elements such as a dancer’s awareness of his or her entire body, a squared torso and arms that aid the rest of the physique. The namesake of this pedagogy emphasized arms used for purposes other than aesthetics. The importance of the arms supports the ideal of awareness of the body since the technique wants ballerinas to use their bodies as a whole, as opposed to the legs primarily working and the arms simply looking pleasant.

Along with the aid of the arms, Vaganova ballet highlights the squaring of the torso to provide stability and strength to the dancer. A torso with shoulders aligned to the hips —instead of twisted—allows the dancer to develop proper strength of the arms. The built-up strength provides an elegant look that this technique strives for, maintained by the arms and legs working together to portray ballet with ease and control. These two aspects contribute to the desired awareness of every aspect of the ballerina’s body by portraying thorough detail and sophistication in performance.

“Agrippina Vaganova… began to explore and develop her system of teaching by thinking of the body as a whole and breaking each movement down into its basic form, and gradually building upon each step into more complex movements to make each step become art. Vaganova teaches how to use the whole body cohesively within its eight levels or years of study. The upper body supports the work of the lower body, and great emphasis is put on awareness of using the correct muscles and holding the proper posture to support the body during movements to avoid injury, and most importantly, being expressive,” Neeley said.

Furthermore, the Vaganova technique emphasizes the significance of the arms and legs working together, as well as èpaulement: the movement of the upper body. In this practice of teaching, the arms, legs, head and shoulders move together and provide the dance with a delicate and coordinated look, such as the variations in Paquita. The Cecchetti method includes similar desires for the arms and legs to work together, as well as the èpaulement emphasis in the French method.

The Vaganova method exemplifies various aspects of the Cecchetti and French styles since Vaganova derived her inspiration from these two sources. However, this pedagogy differs in multiple ways from every other ballet style, including Vagaonva’s two main influences.

The Bournonville method, which arose in Denmark from Danish choreographer August Bournonville, also uses èpaulement. However, these dancers utilize it in different ways than Vaganova dancers. Bournonville appreciated a diagonal èpaulement, in which the head and shoulders face the working leg: the one that moves as opposed to the one standing. This opposes èpaulement in Vaganova which consists of the shoulders facing the rest of the body, but the head looks over the front shoulder. Ballets such as La Sylphide employ these Bournonville characteristics in their choreography.

Another method, Balanchine—also known as the American style—shares several characteristics with Vaganova. Both Balanchine and Vaganova’s techniques fall under the umbrella of classical ballet and feature in famous ballets such as Swan Lake and Giselle. This method, formally developed in the New York City Ballet School, derived considerable inspiration from Vaganova. However, the Balanchine style differs with its emphasis on speed and strength, so the dance world recognizes it as a separate and distinct technique.

These methods, along with multiple others, influenced the world of ballet in various ways. However, Vaganova’s transformation of ballet studios worldwide remains unparalleled. Today, ballet scholars refer to her technique as one of the “main three” methods along with Cecchetti and the Royal Academy — the English style that merges a variety of ballet techniques. Overall, the Vaganova approach influenced the formation and adaptation of copious other methods, as well as maintained a lasting influence on the teaching style that incorporates barre and pas de deux work into modern ballet classrooms.

“Vaganova technique stresses overall consciousness of the body and creates a greater range for expression through the synergy of movement. It emphasizes character portrayal and dramatic expression. Vaganova encourages the dancer to infuse emotion, storytelling, and depth into movement. The technique perceives the body as a whole, with equal utilization of arms, legs, core and facial expressions working together, rather than [for example] primarily the legs doing the work and the rest of the body serving as an aesthetic,” Assistant professor of dance at Kennesaw State University Autumn Eckman said.

With significant differences in each ballet method and multitudinous influence on the culture of ballet, the Vaganova system requires strength from each dancer. The world recognizes Vaganova for its effect and various aspects as it continues to affect ballet classrooms and performances. Even today, family customs such as watching “The Nutcracker” each Christmas display Vaganova’s influence to those who do not know about ballet extensively, as the technique’s presence remains prominent.

“The Vaganova technique is crucial in ballet for its focus on achieving an equal blend of athleticism and grace. It stands out by combining the physicality of classical ballet with a deep understanding of artistic expression. Unlike many other methods, it creates dancers who possess both technical skill and the abilities to convey emotion through their performances,” magnet junior Ellie Huff said.