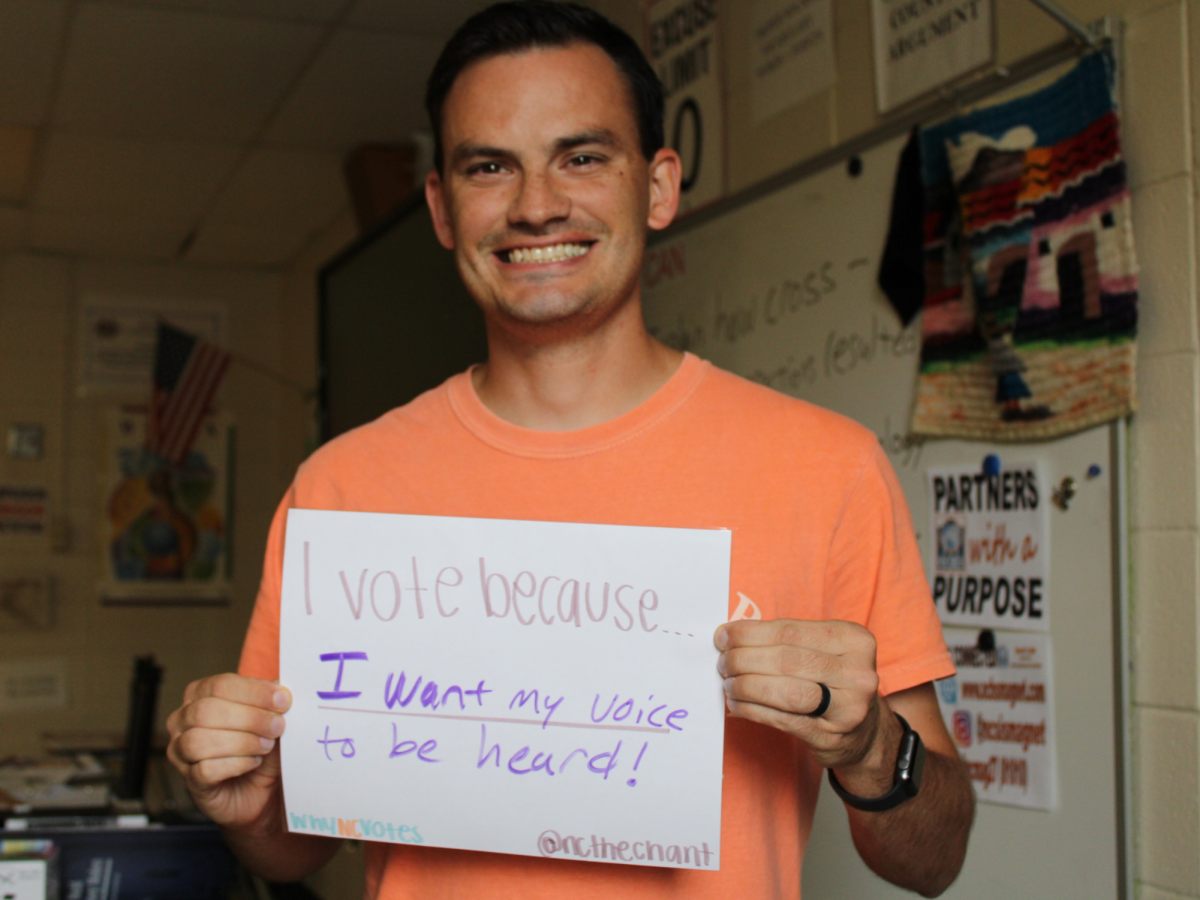

When humans settle into a new environment, psychology pulls individuals to settle and morph the space into an area that matches their personalities. Whether through decorating or meeting new neighbors, integrating oneself into a brand-new place provides a sense of excitement for what lies ahead. For NC’s new Advanced Placement (AP) World History teacher John Mitchell, Jr., that settling took the form of encouraging his newfound school community to vote. Similarly to the students who pass him in the hallways, Mitchell registered to vote as soon as he could during his senior year of high school; as he becomes increasingly familiar with NC’s student body, his understanding of the school’s political efficacy — the belief that an individual’s political action matters — grows exponentially.

“I started that process when I was 17, and that was in 2008. I couldn’t vote in the Presidential election of 2008, but I could vote for governor in 2010. I value that as your way of voting for who represents your ideals. I would say voting matters because when I reflect on history in the AP world, elections in terms of who you feel should be the leader have never been guaranteed. Elections have not been very common in history, and we live in a nation where we have the freedom to vote or not. Some choose to, some don’t. For people who want to but need to be reached out to, it comes down to the simple question of ‘Do you feel like your voice isn’t heard, and if so, why not?’,” Mitchell said.

Mitchell joins a substantial list of civically engaged millennials who show up to their local and national elections. In 2023, the news website Aristotle reported that millennials comprise up to one-fourth of the voter population; in the 2020 Presidential election, 65% of the 30 to 44-year-old demographic cast a ballot for a candidate. Regardless of the political party to which millennials support via their vote, the generation increasingly continues to show up at the ballot box alongside Generation Z (Gen-Z). As a millennial teacher who interacts with students in both Gen-Z and Generation Alpha, Mitchell aims to inspire a sense of collective togetherness in his age group and the young people he reaches daily.

As a world history educator, Mitchell understands the privilege of fair and free elections. In the beginning years of the U.S. citizens lived under tyrannical rule, where their voices did not matter in the eyes of their leaders. Upon a reflection on his studies, Mitchell calls upon the ways that ancient Greeks and Romans conducted direct elections for the first forms of a republic in their societies, and how that has morphed into our modern democracy. In his role as a teacher, he sees these democratic foundations spring up in his job daily — from how classrooms operate to the ways that businesses function, Mitchell feels the presence of democracy in several aspects of his life.

Ultimately, Mitchell believes that a significant component of voter participation lies in the importance of the individual acting in pursuit of the whole. The teacher believes that people may become lost in the grandeur of the election process and could absorb an attitude that one minuscule vote does not carry significant weight. Mitchell proposes a change in attitude and urges people to view voting as a distinct advantage of living in the free world. He believes that regardless of an election’s outcome, the act of projecting one’s voice into the political atmosphere stands as beneficial because citizens can showcase their desires and hopes for the country in which they live. By focusing on the collective benefit that an equitable election allows, Mitchell hopes that the ever-evolving American society can expand their perspectives on how deeply their votes matter. His faith in democracy, belief in progression and desire for a brighter future helps to ensure that a history of voter suppression does not repeat itself.

“I think one of the bigger things to note about getting the chance to vote is essentially getting the opportunity to speak your mind about changes or continuations in policy. You vote for something so much broader than yourself. You vote for what you feel is best for the future, best for the next four to possibly eight years. Typically, I vote for what I feel is best for the future, and with having children, what I feel is best for them and their future. People may vote for a litany of other reasons, but mainly for me it’s gotta go off of the family and what I feel is best for them,” Mitchell said.

![During an election season, several Americans recall the extensive history — and conflict — with how voting has operated. The vast and often frustrating methods of voting used in decades past can allow modern citizens to appreciate the current methods in place, while also remembering the fond memories that occurred on the civic struggle bus. For Advanced Placement (AP) Macroeconomics and honors government and economics teacher Dr. Pamela Roach, her knowledge and lived experiences of different voting eras allow her to cherish her civic duty, and teach her students to do the same. Although it may not be the most efficacious, I think voting is one act of political participation. You [can] write and email your elected representative, whether it's at the local state or national level. [That] has a place in democracy because how else will those elected officials know what we, the people, want? ‘We the people’ is a powerful phrase, and no one takes the time to actually go and let their voice be heard by these individuals. So yeah, your voice matters,” Roach said.](https://nchschant.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/roach-photo-1-1200x900.png)

![For several government and politics educators around the U.S., an election season represents a key time to educate their students through tangible examples. In the case of Advanced Placement (AP) Comparative Government teacher Carolyn Galloway, this opportunity not only excites her but fervently aligns with her zeal for democratic processes. Through her personal and professional experiences with voting and government, Galloway encourages her students — both those who can vote and those who can not — to enter into elections informed about any topics on the ballot. “[Voting] impacts your government, especially on the local level, because not a lot of people vote on the local level. Who you vote for, how you vote, and whether or not you understand what you are voting for impact everything from who your tax commissioner is, to who your president is, to what ballot measures pass. All of those impact the way the government works for you,” Galloway said.](https://nchschant.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/galloway-photo-2-1200x900.png)