When one drums up an ideal of the U.S., different images appear; the aggressive finger-pointing of Uncle Sam, the American flag swinging gallantly in the air or the working class plowing a lush field stands as a few of the heuristics that surface concerning the country’s legacy. Unbeknownst to several Americans, however, those iconic images, as pride-instilling as they stand, represent versions of propaganda. The term, which Britannica defines as the distribution of information through rumors, half-truths, arguments and lies to influence public opinion, has effectively seeped its way into the global lexicon and still serves as a method of effective agenda-pushing for several organizations.

“Propaganda tends to work itself into everyday media quietly, specifically through emotional framing, the reinforcement of political echo chambers, and selective storytelling. I’ve especially noticed it in how outlets may cover international crises — shining a spotlight on one side of a conflict while leaving other perspectives in the margins. I think it’s important to note that what goes unsaid can sometimes be just as influential to the invention of propaganda as what is actually said and that this subtle imbalance shapes not only what people learn about such events, but also how they feel about them,” political science and psychology student at the University of California, Davis and American River College Aarti Sharma said.

Part One: The origins of propaganda

Although the use of the word propaganda began in the early 17th century, the term’s legacy dates back to the age of the ancient Greeks and Romans. In times of political or religious debate, propaganda and counterpropaganda ran rampant, with every side attempting to cement their opinions as “right.” During the 1500s, the monarchs of countries such as England and Spain utilized propaganda to boast the colonial successes of their respective conquerors. The actions of 17th-century Catholic missionaries further cemented the now-name-brand notoriety of propaganda when Pope Gregory XV founded the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith; years later, his successor Pope Urban V witnessed the creation of the College of Propaganda. From the revolutions of the French and the Americans, counterpropaganda was similarly used to turn undecided citizens into non-believers of the respective monarchs.

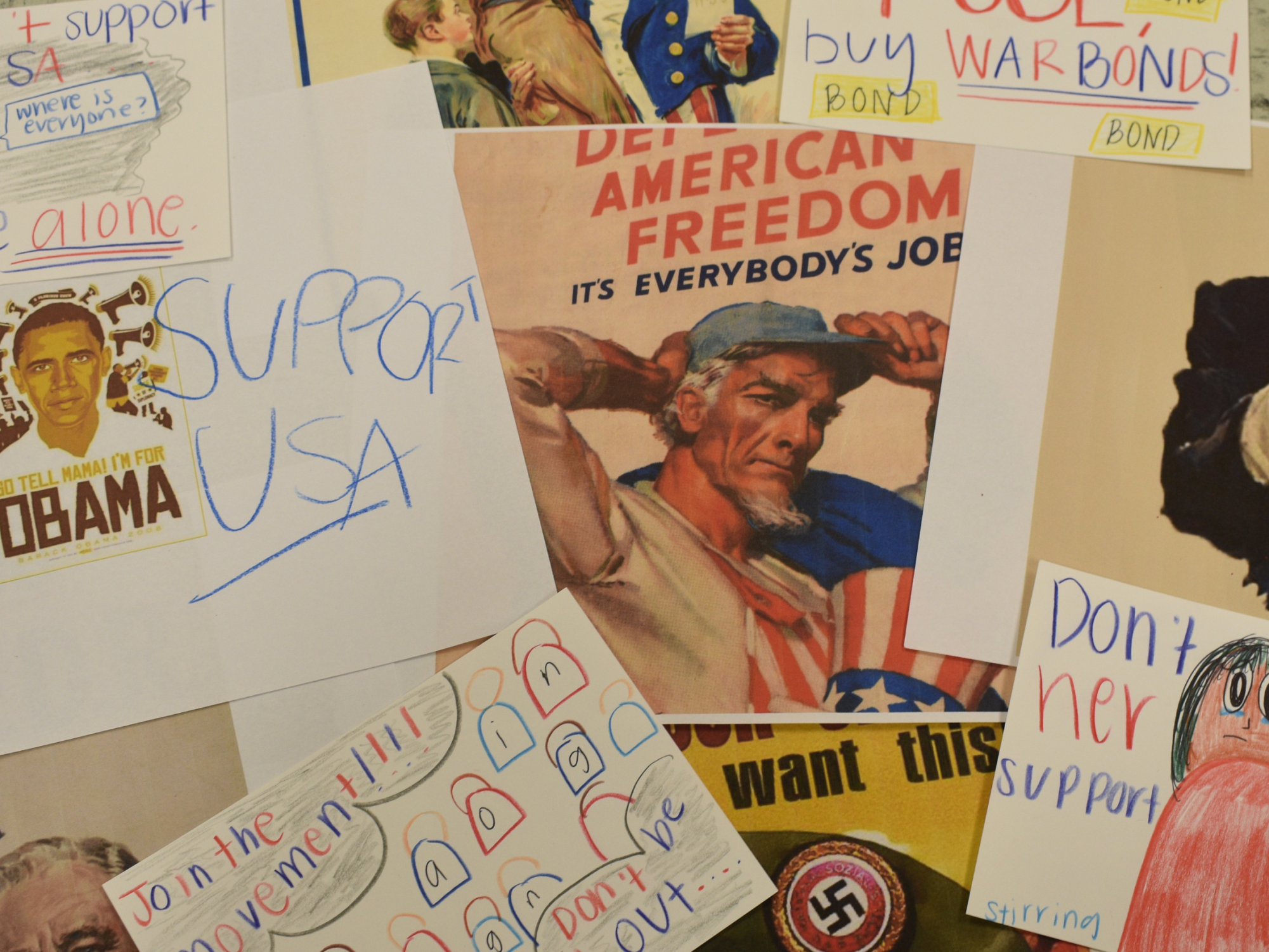

In the aftermath of World War One (WWI), leaders such as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin utilized their emerging post-war platforms to spread messages of communism and fascism, which ultimately took place through various forms of convincing messaging. During the Second World War, both Nazi Germany and the U.S. released unique forms of propaganda in the media, which morphed citizens’ perceptions of the Holocaust as well as the true extent of Hitler’s regime. After Hitler became the Chancellor of Germany, he dedicated members of his cabinet to creating a positive image of the country and counteract negative reports about violence against the Jewish people. American educators, concerned over the potential success that these news releases may harbor over impressionable citizens, began to teach their students how to identify markers of propaganda; to further this education, the Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) continued the same practices. Through mediums such as print, artwork or television, the U.S. used different platforms to highlight the true atrocities of what occurred in concentration camps and to show citizens the full story of the crimes.

The elongated international legacy of propaganda created a space for its stronghold in the U.S. to take form. In 1813, the infamous character of Uncle Sam was born out of a cheeky nickname for the U.S.; as the century progressed, artists grew the caricature, with James Montgomery Flagg creating the version best known to people today, complete with a blue top hat and a well-intentioned scowl. This image was heavily used during WWI to recruit young men for the war effort. During the 1940s, the iconic images of women such as Rosie the Riveter, working diligently at home to support the nation’s soldiers, spread rapidly, encouraging women to contribute to the economy during wartime. Throughout the years, propaganda tackled political and social issues such as school integration, nuclear warfare and presidential campaigning. Although several iconic images rooted in U.S. propaganda came to fruition in the past, their influences — and tactics — still show up in the modern day.

Part Two: How does propaganda work?

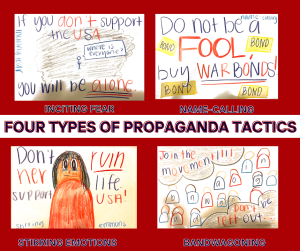

According to Master of Science in Education (MSEd) Kendra Cherry, people utilize tools of persuasion daily. Advertisements or political debates serve as a medium to bring people from one side to another and aim to encourage people in the middle on certain issues to choose a side. Despite the difference between the terms, several people view propaganda and persuasion as synonyms, whereas in reality, propaganda manipulates persuasive tools to generate emotions within audiences. Uniquely to propaganda, tactics such as name-calling, bandwagoning, inciting fear and stirring up emotions arise to create an extreme sense of allegiance to a certain viewpoint, and do so in a manner that criticizes the perceived opposition.

Ultimately, propaganda also works through its appeal to emotions. Through the depiction of crying faces of young children or the elderly suffering from illness and disease, tugging at the heartstrings of unsuspecting viewers helps cement images in people’s minds. Recently in the U.S., significant events such as the COVID-19 pandemic created a space for racist rhetoric to swim through American media. According to Reuters, for example, the Pentagon allegedly released anti-vaccination propaganda targeted against China. By creating images or titles with strong language, capitalizing on shock value to receive engagement for posts dominates modern propaganda. The use of techniques such as clickbait, as well as the technology of artificial intelligence (AI) opens up the capacity for propaganda to convince audiences of a higher degree of half-truths or lies.

“I saw many people particularly affected by propaganda in 2020 especially. With conspiracy theories that were spread about the impact of vaccines on the human body. I saw people trust the racist or homophobic beliefs about the origin of COVID-19. It was crazy to experience. I thought that an easy way to find the answer would be to go to a credible source, but most people preferred to listen to the first thing that supported their polarizing beliefs. I think propaganda is an impactful way for interest groups to push an agenda. It works wonders in today’s society without us even realizing it. I think it’s weird because we’re in a period of both over-intellectualization and everyone preferring to dumb things down,” magnet senior Destiney Jones said.

Part Three: The impact of clickbait and AI

Clickbait, as per Merriam-Webster Dictionary, describes a title or headline that urges viewers to engage with the post, often by using suspicious wording. While people may believe that clickbait does not always serve to create disarray, it uses elements of shock and emotional manipulation that appear in propaganda. Using extreme words such as “you’ll never believe” or “the best” jogs up similar propaganda techniques that urge people to believe opinion over fact, and do so in a way without questioning other ideas.

Similarly, generative AI can help create propaganda images through its diverse set of tools. Although AI-created propaganda can circulate in an attempt to spread awareness — cut to the image of a teary-eyed little girl and her puppy floating around in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene — the platform emerges as a divisive tool meant to push agendas. While viewers of the post may have spread it to showcase the emotional destruction of the storm, several Republicans utilized the post to criticize how the administration of President Joe Biden handled the relief efforts. The political influence that generative AI presents holds near-equal influence on viewers as campaign speeches can. For example, President-elect Donald J. Trump has utilized AI to form images of himself, with his recent creation resulting from his proposal to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau for Canada to join the U.S. Similarly, his ally and founder of SpaceX, Elon Musk, shared a photo of Vice President Kamala Harris wearing a communist uniform on his X account, where millions of his followers bore witness.

Although AI can create photos to help share productive information, several extremist groups abuse the platforms to engender inappropriate pictures of celebrities and public figures, intending to use their name and likenesses to encourage their fan bases to follow ideologies. As recently as the 2024 Presidential election, Trump utilized the image of pop star Taylor Swift in AI-generated political posters, with a significant photo showcasing Swift in an Uncle Sam-esque fashion. Audiences can use any tools at their disposal of material in the public domain, so they can create inappropriate content for mass distribution; if audiences can not tell the difference between real or false images, impressionable audiences will become scarred.

Part Four: How to combat propaganda’s impact

In the face of persistent propaganda, audiences must develop the essential skills necessary to combat opinionated attacks. As concluded by a study from Media Literacy Now, only 38% of adult respondents learned how to analyze media messaging in high school; however, 84% of those surveyed supported required media education in schools, which represents a significant degree of support for efficient training in media consumption. Improving media literacy stands as the premiere way for citizens to combat the easy influence of biased media. The ability to read text and form conclusions represents an effective manner to read between the lines of propaganda and craft logical inferences.

Media literacy similarly ties to evaluating the sources one consumes. According to the organization AllSides, media bias exists in different channels through strategies such as spinning facts, sensationalism and bias by omission; each one of the 16 tactics listed on their websites can provide audiences with an overdramatized — or even incorrect — idea of policies or politicians. Even within renowned television stations like Fox News or The Atlantic, bias can permeate news reporting. The AllSides Media Bias Chart showcases various sources that harbor liberal, left-leaning, centrist, right-leaning or conservative views, and demonstrates the spectrum of opinions in the news centers people watch daily.

“I’ve heard that many people, and this is especially true for young people, get most of their ‘news’ from social media. My advice on how to combat the impacts of propaganda: read newspapers and other sources beyond social media. I’ve heard educators talk about ‘lateral reading.’ Instead of simply reading one thing and trying to understand, find other discussions of the topics, especially from different perspectives,” Professor of History and Assistant Department Chair at Kennesaw State University Dr. David B. Parker said.

As the world continues to globalize and technology quickly advances, humans must develop the tools necessary to read their media, analyze the text and not fall prey to the pitfalls of propaganda. Although bias can worm itself into the lexicon of different news outlets, several tools lie at the disposal of audiences to consume stories responsibly. Combating propaganda requires effort from every American who consumes media; to ensure that no one citizen falls prey to its impacts, everyone must cultivate a concerted effort to read between the lines.