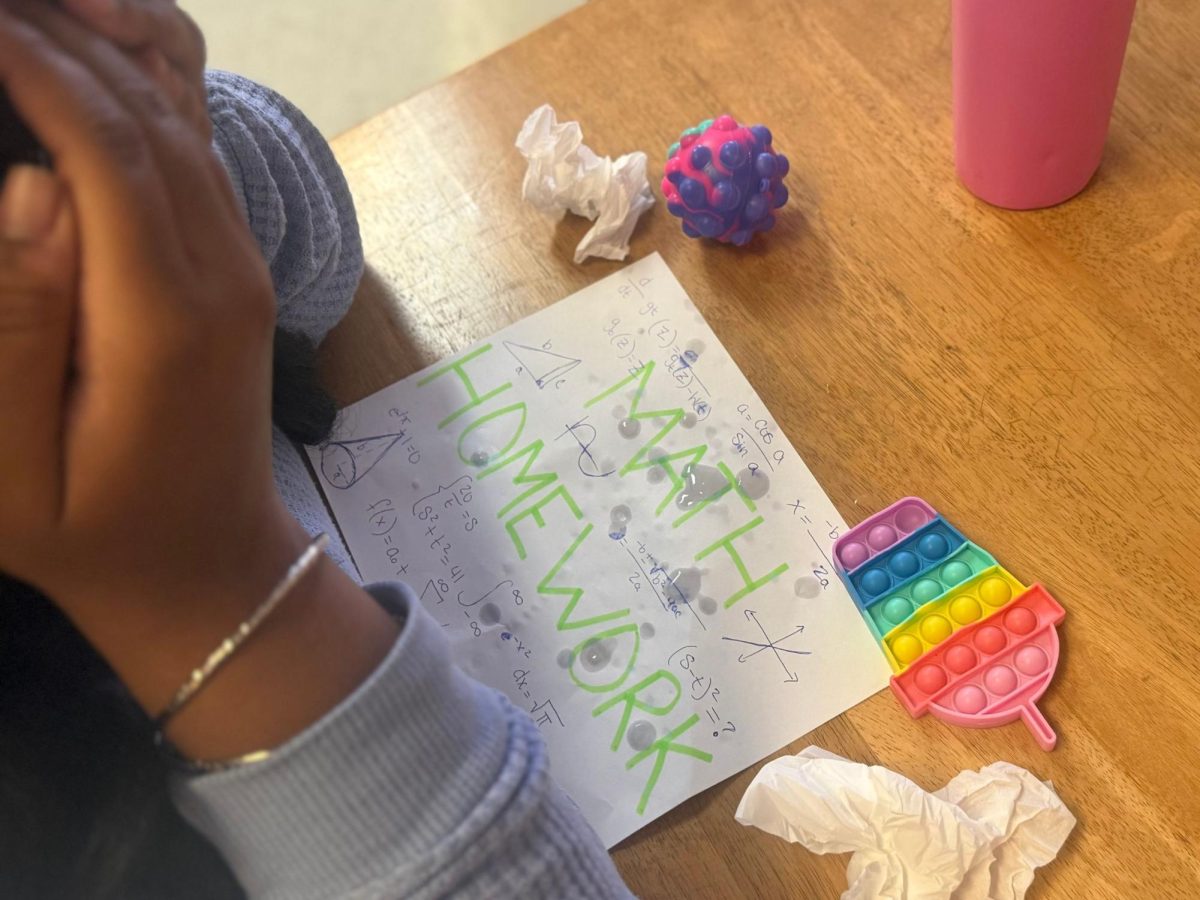

As young journalists decide the route of work they wish to tend to, various reporters jump into adrenaline-filled environments to cover the news. While these journalists research the areas where they wish to report, factors of safety rise. Each year, Reporters Without Borders publishes the annual World Press Freedom (WPF) Index for 180 countries and territories around the globe to examine the acts of violence journalists have faced within the specified time period. In accordance, the 2023 WPF Index explains that the environment for journalists becomes known as very serious in 31 countries, difficult in 42, problematic in 55 and satisfactory in 52. As these percentages vary, the dangers journalists face in all countries, specifically developing countries, rise.

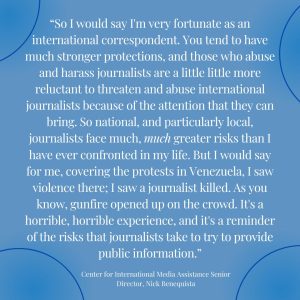

“One of the things that’s been most persistent, unfortunately, is the impunity with which this violence happens. So in nine out of 10 cases, no one is held accountable, arrested or charged in violent crimes against journalists and that is the key challenge, reducing that impunity because we know that when impunity falls, folks are less likely to commit crimes against journalists. So we really need to solve the impunity crisis. Unfortunately, I think the safety of journalists has gotten a lot more complicated because it’s not just about the killings of journalists. Even as that persists, there are new ways of attacking journalists,” Senior Director of the Center for International Media Assistance Nick Benequista said.

Policies

Currently, heated debate reigns over the journalism field due to the lack of protective services journalists encounter while in developing countries. For example, Mexico, deemed as the ultimate danger zone for journalists because of the shortfall of federal protective policies, continues to hold a stigma surrounding its inadequate press safety policies. For instance, Article Seven of the Mexican Constitution fully protects press freedoms, so in various cases, censorship occurs through threats and direct attacks against journalists rather than overtly restrictive laws. Mexico’s federal mechanism, the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, protects journalists in the country who remain at extreme risk or receive extensive threats due to their work. While this number significantly decreased within the last seven years of its creation, a total of eight journalists have died in Mexico, resulting in a need for reformation and strengthening of the institution — especially with the rise of advanced technology sneaking into their publication offices.

“Sophisticated spyware was only once found in the most advanced nations of the world. It’s now been commercialized and very advanced spyware called Pegasus, sold by the NSO Group, an Israeli company, has been found on the phones of journalists all around the world, many in Mexico. For instance, there was a newsroom in El Salvador in which just about every member of the newsroom had Pegasus spyware on their phones. We know this because The Citizen Lab, a Toronto-based digital forensic civil society group, was able to discover it on their phones. And we know this because Forbidden Stories did some investigations into the use of Pegasus, also exposing the use of this spyware. So spyware is becoming a huge threat, as well as other forms of surveillance online including doxxing and harassment that have become really acute, especially for women journalists,” Benequista said.

In a similar view, Nicaragua has encountered a similar set of issues alongside Mexico. With Nicaragua’s population of almost seven million, President Daniel Ortega quickly damaged their independent media throughout his fourth consecutive term. Ortega’s regime currently consists of engaging in surveillance, curtailing press freedoms, arresting political opponents and sending opposing voices within the country — mainly including journalists — into exile as punishment. Over the course of a decade, in response to limiting press freedoms, the Ortega family bought multiple of the country’s television stations before the government, once again accelerating attacks on the press in ways including the digitalization of well-known newspapers.

In a different view, Cuba — a totalitarian communist country — follows a closely monitored government that pushes for immense censorship and restrictive internet freedoms. Authorities have blocked independent news sites while also threatening independent journalists with death penalties since the Cuban Constitution directly prohibits privately owned media forms. With these blocked news sites, higher powers aim to shut down websites to limit access to information deemed critical to the country, limiting what they publish and cutting journalists’ wages.

Wages

In other cases, journalists have faced criticism from corrupt governments when traveling to such developing countries. These governments limit the research reporters generate and the content they publish. Specifically, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) owns about 80% of well-known media outlets throughout the country, meaning politicians heavily critique the incoming information. In other terms, politicians will utilize these media outlets for their own sake with political propaganda and harsh publicity.

While a wealth of traveling journalists face jarringly low salaries, the reporters’ wages in the DRC depend on the articles they publish. This factor allows politicians to limit published work both domestically and nationwide — leading to lost wages. With the drawback of information these publications withhold from audiences, young journalists become limited from the real experiences reporters currently face. Whether wages vary based on gender or ethnicity, myriad journalists face these struggles head-to-head from a young age. However, while limiting what work becomes published, conflict arises surrounding whether authorities should receive the ability to censor journalists.

Censorship

Understanding how politicians repeatedly limit the influx of news reports from various publications also exemplifies the harsh reality of censorship. Kyaw Thu — a journalist based in Myanmar — dove into a research study in which he discovered how the long-term impact of censorship of the media changed the nature and overall quality of the press. The Press Scrutiny and Registration Division (PSRD), the strict Orwellian censorship board under the military government in Myanmar, requires reporters to submit at least two-thirds of the draft of their upcoming articles about two-to-three days in advance so that the board can pre-censor sensitive issues. Due to this requirement, editors from the publications claimed that nearly 30% to 40% of articles appeared heavily censored or unpublished each week.

These articles’ suspension from publication brought about mistrust within journalists and their community since it blocked the flow of information from the public. As of January 2024, the WPF Index holds Myanmar 171 out of 180 countries while in 2023, Myanmar held 173 place. Myanmar continues to hold a low stance amongst other countries for various factors including the killing of three journalists, 60 detained journalists and three detained media workers leading up to today. To help aid these issues, Reporters Without Borders launched a global campaign in Thailand to provide greater protection for Myanmar journalists with new equipment including laptops, mobile devices and digital security tools, specifically for defense against the Myanmar government. While Reporters Without Borders has started movements to protect journalists, other organizations have risen, bringing concern towards journalist safety in and out of the publication office.

“It’s difficult to understand if you are actively being oppressed or if you are being abused or being taken advantage of if you don’t know what rights you are supposed to have and how far the law protects you. Some people don’t know that there are certain protections if you are being arrested or in jail or that you have certain legal protections in the case of protest that are really important. The right to free speech and the right of people to be able to express their opinions is foundational to a functioning democratic society and so I think it’s really important for people to be able to understand their rights so that they can express their democratic principles,” Advanced Placement (AP) Comparative Government and Politics teacher Carolyn Galloway said.

Organizations

The rise of concern surrounding journalist protection led the Forbidden Stories publication to advocate for strained reporters. Forbidden Stories aims to protect journalists under imprisonment, abduction or murder to secure their information, and ultimately continue their investigations after death. Despite the threats their journalists face, this organization helps bring awareness to the crimes against reporters.

“In Ethiopia I had my sources threatened. I had to be very careful when speaking to people in the Somali region because journalists who had reported in that region previously had been arrested. The names of the sources that they had spoken with had been arrested too. It’s not clear what happened to some of those folks and it’s a reminder of the risks that journalists take to try to provide public information. And, you know, there’s a lot online, and citizens take great risks to tell their stories to journalists. And I think for me that whole experience really reminded me of how important the job is. If these people are willing to risk their lives to have their stories told, the responsibility of the journalist to tell those stories well and to reach a wide audience with them is really tremendous,” Benequista said.

Under Forbidden Stories, the Safebox Network — an extension of the publication that helps protect journalists — created training sessions in countries where journalists have faced life-threatening events and threats within. For example, in Mexico and Guatemala, the Safebox Network helped train and equip nearly 60 journalists surrounding topics such as safety issues, self-defense and first-aid skills. This network expanded within the countries leading 33 new members and nine media outlets to join the Forbidden Stories organization and to now receive protection against the government’s lack of press freedoms for reporters. The Safebox Network and Forbidden Stories stand as a couple of the various organizations that successfully aid journalists within their field of work.

While observing the degree of threatened journalists within outside countries, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) focuses on the unjust deaths of killed reporters. The organization further dives into each country — if applicable — examining death rates of the common journalist, while also showcasing the country’s response to unsolved cases since 1993. Recently, as of September 19, UNESCO signed an agreement to join forces with the U.S. to create and fund a variety of projects for the safety of journalists and freedom of expression with a focus on four regions: Africa, the Arab States, Latin America, the Caribbean and Eastern Europe.

“Journalism is how people know what is going on in the world, whether that be good or bad news. It’s important to protect our freedom of speech and press. When journalists are going out into developing countries to report on what’s going on, there’s a huge risk they are taking. But I also think that’s what makes those stories so interesting. They’re out there, digging into why things are happening and are going to report on the truth, not what their government is telling the world. It’s important for journalists to be safe during these situations, otherwise we won’t ever know what’s truly going on. There’s been a few instances at my station where a reporter has gone out live and they’re fronting their story, and people are harassing them, making them feel unsafe,” NC alumni Haley Kish said.

Independent journalists around the world in countries such as Indonesia and Costa Rica, for example, continue to share exceedingly needed perspectives of journalist conditions within their respective countries with one another, aiming to devise new ideas to tackle global issues. While these issues target professionals, student journalism programs learn from past experiences around the world to educate upcoming journalists on the reality of reporting outside of the classroom. At NC, The Chant values educating the publication staff on ethics to ensure student freedoms remain protected — The Chant encourages each student to understand their rights as a journalist through books including “A Newshound’s Guide to Student Journalism.” As writers learn to battle the negative experiences in their field of work, upcoming networks and organizations rise in hopes of providing a brighter future for aspiring journalists.