“Tell my story”: Holocaust survivor touches 10th Magnet students in powerful lecture

Ms. Weingarten, a holocaust survivor who saved her sister from being killed by the infamous Dr. Death in Auschwitz, describes her story because “we must remember, always.”

November 15, 2016

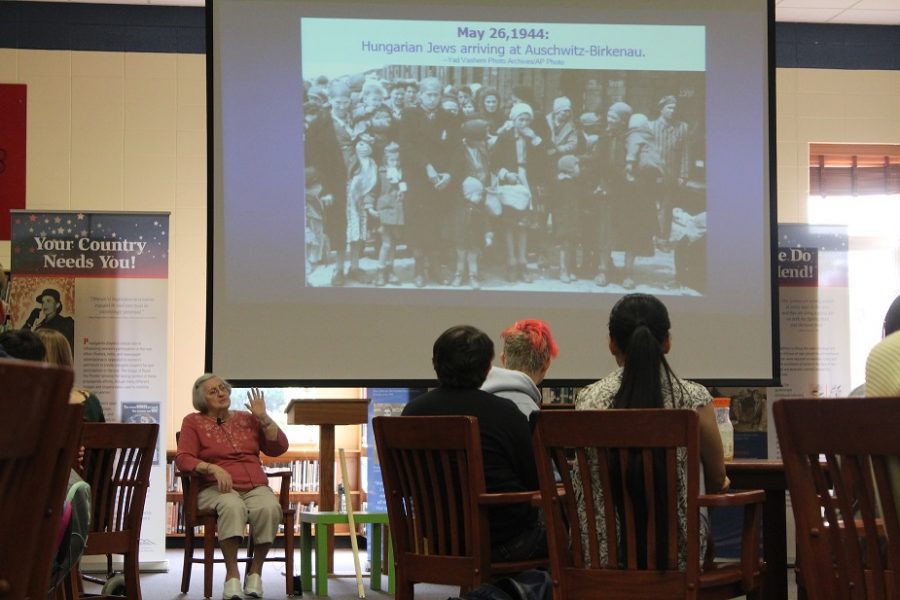

On Monday, November 14, 92 year-old Helen Weingarten related her experiences as a Holocaust survivor to Magnet sophomores and Mrs. Rankenburg’s AP US History class in NC’s media center to a silent and respectful crowd during third period.

Weingarten, an Orthodox Jew, grew up in Romania with five sisters and three brothers. She often took care of her nieces and nephews, and she recalled such experiences with them fondly.

In the late 1930s, Nazis arrived in her small town, rounding Jewish families up by numbers and sending them off by trains into Poland. When exiting the train cars, Nazis instructed families to leave their overnight suitcases on the train for later transport to the “hotel” booked for their stay. Helen looked up at that moment, and saw a sign that read “Auschwitz.”

Officers in Auschwitz split all individuals into groups based on age and gender. Women and girls, forced to shave their heads, risked their life at disobedience of the order.

“I didn’t know who my sisters were. People look different without hair,” Weingarten said.

Nazis killed Weingarten’s nieces and nephews before their arrival, and her parents lay murdered at the death camp.

“Every day, I didn’t know if I would survive to see the next,” Weingarten said.

Each day, groups of thirty received one small jar of soup to share throughout the day. Every week, they received a new change of clothes to prevent the spread of lice. Nazis did not enter rooms due to fear of catching illnesses, and Weingarten and others took that opportunity to practice their religion in their rooms without fear, praying each day for their survival.

Josef Mengele, the camp’s physician, often referred to as “Doctor Death” by Weingarten and others in the camp, used every small complication as a ticket to the gas chamber. Her sister stood in line for the gas chamber minutes from her demise, but Weingarten risked both of their lives by pulling her out to safety.

“I don’t know why I did it,” Weingarten said, “but I saved her life. She lived because of me.”

Captivating students with her words, Weingarten stayed afterwards to take selfies with each student who wanted one, held each of their hands, and wished them a full life where they would share her story to remember.

Months later when Weingarten stood in line, five minutes before her death sentence, a Nazi grabbed a group of women, including her, to send to work at a labor camp as an alternative. After six months of enduring Auschwitz, Weingarten arrived in Germany to work against her will where Americans liberated her soon after.

Helen Weingarten married and had children, grandchildren, and even a great grandchild. Seventy years later, she still remembers details of her experience in the Holocaust and travels around schools, synagogues, and other groups to share her story.

“I went to take a picture with her, and so she held my hand,” sophomore Abigail Spence said. “After we took the picture, she didn’t let go. She turned to me and said, ‘I hope what happened to me will never happen to you kids.’”

Weingarten is a part of a series of Holocaust survivors that feel compelled to tell their stories through the Georgia Commission on the Holocaust. The cultural programming component of the NCSIS Magnet program contacted Judy Schancupp through the commission to set up this guest speaking experience. The commission also offers other exhibits that travel to schools, including one depicting the story of a brave African American liberator of a Nazi camp during World War II.

Weingarten was originally scheduled to speak two weeks earlier, but she fell ill and was in the hospital, but quickly bounced back to her health.

Weingarten ended her talk with an important request to all the listeners in the media center.

“Tell your parents, your aunts or uncles, anyone who will listen. Tell them my story,” she said. “People need to know what happened to us.”